(Press-News.org) In the near future, physicians may treat some cancer patients with personalized vaccines that spur their immune systems to attack malignant tumors. New research led by scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has brought the approach one step closer to reality.

Like flu vaccines, cancer vaccines in development are designed to alert the immune system to be on the lookout for dangerous invaders. But instead of preparing the immune system for potential pathogen attacks, the vaccines will help key immune cells recognize the unique features of cancer cells already present in the body.

Scientists at Washington University already are evaluating personalized cancer vaccines in patients with metastatic melanoma in a clinical trial led by Gerald Linette, MD, PhD, and Beatriz Carreno, PhD at Siteman Cancer Center. The researchers also are working to use the vaccines against breast, brain, lung, and head and neck cancers, and additional trials are anticipated in the next year or two.

In the new study, which appears Nov. 27 in an issue of Nature focused on cancer and the immune system, scientists tested investigational vaccines in computer simulations, cell cultures and animal models. The results showed that the vaccines could enable the immune system to destroy or drive into remission a significant number of tumors. For example, the vaccines cured nearly 90 percent of mice with an advanced form of muscle cancer.

"This is proof that personalized cancer vaccines can be very powerful and need to be applied to human cancers now," said senior author Robert Schreiber, PhD, the Alumni Professor of Pathology and Immunology and director of the university's Center for Human Immunology and Immunotherapy Programs.

Creating a personalized vaccine begins with samples of DNA from a patient's tumor and normal tissue. Researchers sequence the DNA to identify mutant cancer genes that make versions of proteins found only in the tumor cells. Then they analyze those proteins to determine which are most likely to be recognized and attacked by T cells. Portions of these proteins are incorporated into a vaccine to be given to a patient.

Years of studying cancer genetics and of the immune system's interactions with cancer have made the vaccine strategy possible.

The technique was inspired by a therapy scientists call checkpoint blockade. This immune-based cancer treatment, which has been successful against advanced lung and skin cancers in clinical trials, takes advantage of immune T cells that are present in many tumors but have been shut off by cancer cells.

The cancer cells shut off the T cells by activating a safety mechanism called the checkpoint system. This system helps prevent immune cells from attacking the body's own tissues.

Checkpoint blockade takes the brakes off T cells, unleashing their destructive capabilities on the tumors. But the approach also increases the chances that those same immune cells erroneously will attack healthy tissue, causing serious autoimmune disease.

"We thought it would be safer to find ways to identify the mutated tumor proteins that are the specific targets of the reactivated T cells that attack the tumors," Schreiber said. "We believe we can incorporate those proteins into vaccines that only unleash the T cells on the tumors, and so far, our tests have been very successful."

INFORMATION:

The research was made possible in part by Washington University's Center for Human Immunology and Immunotherapy Programs, which provides shared laboratory facilities and other support to aid the bench-to-bedside development of immunotherapy research.

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital Cancer Frontier Fund, the Cancer Research Institute, Susan G. Komen, and the WWWW Foundation.

Gubin MM, Zhang X, Schuster H, Caron E, Ward JP, Noguchi T, Ivanova Y, Hundal J, Arther CD, Krebber W-J, Mulder GE, Toebes M, Vesely MD, Lam SSK, Korman AJ, Allison JP, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH, Pearce EL, Schumacher TN, Aebersold R, Rammensee H-G, Melief CJM, Mardis ER, Gillanders WE, Artyomov MN, Schreiber RD. Checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy targets tumor-specific mutant antigens. Nature. Nov. 27, 2014.

Washington University School of Medicine's 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient-care institutions in the nation, currently ranked sixth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

LOS ANGELES - November 26, 2014 - Work supported by the Stand Up To Cancer (SU2C) - Cancer Research Institute (CRI) - Immunology Translational Research Dream Team, launched in 2012 to focus on how the patient's own immune system can be harnessed to treat some cancers have pioneered an approach to predict why advanced melanoma patients respond to a new life-saving melanoma drug. This new drug, pembrolizumab (Keytruda), was recently approved by the FDA. These findings are reported in Nature online November 26, 2014, ahead of print in the journal.

Over a two-year study, ...

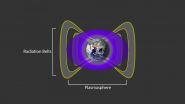

High above Earth's atmosphere, electrons whiz past at close to the speed of light. Such ultrarelativistic electrons, which make up the outer band of the Van Allen radiation belt, can streak around the planet in a mere five minutes, bombarding anything in their path. Exposure to such high-energy radiation can wreak havoc on satellite electronics, and pose serious health risks to astronauts.

Now researchers at MIT, the University of Colorado, and elsewhere have found there's a hard limit to how close ultrarelativistic electrons can get to the Earth. The team found that ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - The use of renewable energy in the United States could take a significant leap forward with improved storage technologies or more efforts to "match" different forms of alternative energy systems that provide an overall more steady flow of electricity, researchers say in a new report.

Historically, a major drawback to the use and cost-effectiveness of alternative energy systems has been that they are too variable - if the wind doesn't blow or the sun doesn't shine, a completely different energy system has to be available to pick up the slack. This lack ...

Two donuts of seething radiation that surround Earth, called the Van Allen radiation belts, have been found to contain a nearly impenetrable barrier that prevents the fastest, most energetic electrons from reaching Earth.

The Van Allen belts are a collection of charged particles, gathered in place by Earth's magnetic field. They can wax and wane in response to incoming energy from the sun, sometimes swelling up enough to expose satellites in low-Earth orbit to damaging radiation. The discovery of the drain that acts as a barrier within the belts was made using NASA's ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- A new study led by Brown University reports that older learners retained the mental flexibility needed to learn a visual perception task but were not as good as younger people at filtering out irrelevant information.

The findings undermine the conventional wisdom that the brains of older people lack flexibility, or "plasticity," but highlight a different reason why learning may become more difficult as people age: They learn more than they need to. Researchers call this the "plasticity and stability dilemma." The new study suggests ...

VIDEO:

When people hear another person talking to them, they respond not only to what is being said -- those consonants and vowels strung together into words and sentences --but also...

Click here for more information.

When people hear another person talking to them, they respond not only to what is being said--those consonants and vowels strung together into words and sentences--but also to other features of that speech--the emotional tone and the speaker's gender, for instance. ...

Older people can actually take in and learn from visual information more readily than younger people do, according to new evidence reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on November 26. This surprising discovery is explained by an apparent decline with age in the ability to filter out irrelevant information.

"It is quite counterintuitive that there is a case in which older individuals learn more than younger individuals," says Takeo Watanabe of Brown University.

Older individuals take in more at the same time as the stability of their visual perceptual ...

Enzymes inside cells that normally repair damaged DNA sometimes wreck it instead, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have found. The insight could lead to a better understanding of the causes of some types of cancer and neurodegenerative disease.

In a paper to be published online Nov. 27 in Molecular Cell, the researchers explain how the recently discovered mechanism of DNA damage occurs when genetic transcripts, composed of RNA, stick to the DNA instead of detaching from it.

Certain enzymes, called endonucleases, are attracted to DNA/RNA hybrids ...

Researchers at the Center for iPS Cell Research and Application (CiRA), Kyoto University, show that induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells can be used to correct genetic mutations that cause Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). The research, published in Stem Cell Reports, demonstrates how engineered nucleases, such as TALEN and CRISPR, can be used to edit the genome of iPS cells generated from the skin cells of a DMD patient. The cells were then differentiated into skeletal muscles, in which the mutation responsible for DMD had disappeared.

DMD is a severe muscular degenerative ...

Mutations in the KRAS gene have long been known to cause cancer, and about one third of solid tumors have KRAS mutations or mutations in the KRAS pathway. KRAS promotes cancer formation not only by driving cell growth and division, but also by turning off protective tumor suppressor genes, which normally limit uncontrolled cell growth and cause damaged cells to self-destruct.

A new University of Iowa study provided a deeper understanding of how KRAS turns off tumor suppressor genes and identifies a key enzyme in the process. The findings, published online Nov. 26 in the ...