(Press-News.org) 27 November 2014 - Anopheles mosquitoes are responsible for transmitting human malaria parasites that cause an estimated 200 million cases and more than 600 thousand deaths each year. However, of the almost 500 different Anopheles species, only a few dozen can carry the parasite and only a handful of species are responsible for the vast majority of transmissions. To investigate the genetic differences between the deadly parasite-transmitting species and their harmless (but still annoying) cousins, an international team of scientists, including researchers from the University of Geneva's Faculty of Medicine and the SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, sequenced the genomes of sixteen Anopheles species from around the globe. Two articles published in today's issue of Science describe detailed genomic comparisons of these mosquitoes and the deadliest of them all, Anopheles gambiae. These results offer new insights into how these species are related to each other and how the dynamic evolution of their genomes may contribute to their flexibility to adapt to new environments and to seek out human blood. These newly-sequenced genomes represent a substantial contribution to the scientific resources that will advance our understanding of the diverse biological characteristics of mosquitoes, and help to eliminate diseases that have a major impact on global public health.

Malaria parasites are transmitted to humans by only a few dozen of the many hundreds of species of Anopheles mosquitoes, and of these, only a handful are highly efficient disease-vectors. Thus although about half the world's human population is at risk of malaria, most fatalities occur in sub-Saharan Africa, home of the major vector species, Anopheles gambiae. Variation in the ability of different Anopheles species to transmit malaria - known as "vectorial capacity" - is determined by many factors, including feeding and breeding preferences, as well as their immune responses to infections. Much of our understanding of many such processes derives from the sequencing of the Anopheles gambiae genome in 2002, which has since facilitated many large-scale functional studies that have offered numerous insights into how this mosquito became highly specialized in order to live amongst and feed upon humans.

Until now, the lack of such genomic resources for other Anopheles limited comparisons to small-scale studies of individual genes with no genome-wide data to investigate key attributes that impact the mosquito's ability to transmit parasites. To address these questions, researchers, led by Professor Nora Besansky from the University of Notre Dame, Indiana, sequenced the genomes of 16 Anopheles species. "We selected species from Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America," explained Prof. Besansky, "that represent a range of evolutionary distances from Anopheles gambiae, a variety of ecological conditions, and varying degrees of vectorial capacity." DNA sequencing and assembly efforts at the Broad Institute were funded by the NHGRI and led by Dr Daniel Neafsey, with samples obtained from mosquito colonies maintained through BEI Resources at the United States Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, and wild-caught or laboratory-reared mosquitoes from scientists in Australia, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, China, Equatorial Guinea, India, Indonesia, Iran, Kenya, Malaysia, Myanmar, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, South Africa, Thailand, The Gambia, Vanuatu, Vietnam, and Zimbabwe. "Getting enough high-quality DNA samples for all species was a challenging process," said Dr Neafsey, "and we had to design and apply novel strategies to overcome the difficulties associated with high levels of DNA sequence variations, especially from the wild-caught samples."

With genome sequencing complete, scientists from around the world contributed their expertise to examine genes involved in different aspects of mosquito biology including reproductive processes, immune responses, insecticide resistance, and chemosensory mechanisms. These detailed studies involving so many species were facilitated by large-scale computational evolutionary genomic analyses led by Dr Robert Waterhouse from Prof. Zdobnov's group at the University of Geneva's Faculty of Medicine and the SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. Dr Waterhouse, a Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology said that, "A project of this scale required detailed planning and extensive cooperation; the European Union's Marie Curie programme recognized these qualities in my research proposal and awarded me a fellowship to visit MIT and study these mosquitoes."

The researchers carried out interspecies gene comparisons with the Anopheles and other insects, to identify equivalent genes in each species and highlight potentially important differences. "We used similarities to genes from Anopheles gambiae and other well-studied organisms such as the fruit fly to learn about the possible functions of the thousands of new genes found in each of the Anopheles genomes," explained Dr Waterhouse. Examining gene evolution across the Anopheles revealed high rates of gene gain and loss, about five times higher than in fruit flies. Some genes, such as those involved in reproduction or those that encode proteins secreted into the mosquito saliva, have very high rates of sequence evolution and are only found in subsets of the most closely-related species. "These dynamic changes," said Dr Neafsey, "may offer clues to understanding the diversification of Anopheles mosquitoes; why some breed in salty water while others need temporary or permanent pools of fresh water, or why some are attracted to livestock while others will only feed on humans."

The newly-available genome sequences provided conclusive evidence of the true relations amongst several species that are very closely related to Anopheles gambiae but nevertheless show quite different traits that affect their vectorial capacity. This study, examining very recent evolution amongst very closely-related species, was led by Prof. Besansky and Dr Michael Fontaine (formerly of the University of Notre Dame and now at the University of Groningen, The Netherlands). "The question of the true species phylogeny has been a highly contentious issue in the field," said Prof. Besansky, "our results show that the most efficient vectors are not necessarily the most closely-related species, and that traits enhancing vectorial capacity may be gained by gene flow between species." This study substantially improves our understanding of the process of gene flow - a process believed to have occurred from Neanderthals to the ancestors of modern humans - and how it may affect the evolution of common and distinct biological characteristics of mosquitoes such as ecological flexibility and vectorial capacity.

These two very different evolutionary timescales - spanning all the Anopheles or focusing on the subset of very closely-related species - offer distinct insights into the processes that have moulded these mosquito genomes into their present-day forms. Their dynamic evolutionary profiles may represent the genomic signatures of an inherent evolvability that has allowed Anopheles mosquitoes to quickly exploit new human-generated habitats and become the greatest scourge of humankind.

INFORMATION:

This news release is available in German.

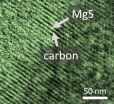

The Helmholtz Institute Ulm (HIU) established by Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) is pushing research relating to batteries of the next and next-but-one generations: A research team has now developed an electrolyte that may be used for the construction of magnesium-sulfur battery cells. With magnesium, higher storage densities could be achieved than with lithium. Moreover, magnesium is abundant in nature, it is non-toxic, and does not degrade in air. The new electrolyte is now presented in the journal "Advanced Energy ...

TORONTO, December 1, 2014 - For the first time, a team of astronomers - including York University Professor Ray Jayawardhana - have measured the passing of a super-Earth in front of a bright, nearby Sun-like star using a ground-based telescope. The transit of the exoplanet 55 Cancri e is the shallowest detected from the ground yet, and the success bodes well for characterizing the many small planets that upcoming space missions are expected to discover in the next few years.

The international research team used the 2.5-meter Nordic Optical Telescope on the island of ...

Women with a mental illness (including depression, anxiety and serious mental illnesses) are less likely to be screened for breast cancer, according to new research published in the BJPsych (online first).

The research was led by Dr Alex J Mitchell, consultant psychiatrist in the Department of Cancer Studies, University of Leicester.

Studies have previously shown there is a higher mortality rate due to cancer in people with mental illness, perhaps because of high rates of risk factors such as smoking. In addition, it appears cancer is often detected later in those with ...

Off the coast of Schleswig-Holstein at the exit of Eckernförde Bay is a hidden treasure, but it is not one of chests full of silver and gold. It is a unique scientific record. Since 1957, environmental parameters such as oxygen concentrations, temperature, salinity and nutrients have been measured monthly at the Boknis Eck time series station. "It is one of the oldest active time series stations for this kind of data worldwide," explains the scientific coordinator Prof. Dr. Hermann Bange from GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel. To date, however, the long ...

Graphene's great strength appears to be determined by how well it stretches before it breaks, according to Rice University scientists who tested the material's properties by peppering it with microbullets.

The two-dimensional carbon honeycomb discovered a decade ago is thought to be much stronger than steel. But the Rice lab of materials scientist Edwin "Ned" Thomas didn't need even close to a pound of graphene to prove the material is on average 10 times better than steel at dissipating kinetic energy.

The researchers report in the latest edition of Science that firing ...

WASHINGTON - In certain circumstances, women may be more effective than men when negotiating money matters, contrary to conventional wisdom that men drive a harder bargain in financial affairs, according to a new meta-analysis published by the American Psychological Association.

"One reason men earn higher salaries than women could be women's apparent disadvantage vis-à-vis men in some types of negotiations," said lead author Jens Mazei, a doctoral candidate at Germany's University of Münster. "But we discovered that this disadvantage is not inevitable; rather, ...

EAST LANSING, Mich. --- Scientists have presented the most comprehensive evidence to date that climate extremes such as droughts and record temperatures are failing to change people's minds about global warming.

Instead, political orientation is the most influential factor in shaping perceptions about climate change, both in the short-term and long-term, said Sandra Marquart-Pyatt, a Michigan State University sociologist and lead investigator on the study.

"The idea that shifting climate patterns are influencing perceptions in the United States - we didn't find that," ...

It is said to represent a "cosmic constant" found in the curvature of elephant tusks, the shape of a kudu's horn, the destructive beauty of Hurricane Katrina, and in the astronomical grandeur of how planets, moons, asteroids and rings are distributed in the solar system, to name but a few.

Now, researchers from the Universities of the Witwatersrand and Pretoria are also suggesting that the "Golden Ratio" - designated by the Greek symbol ∅ (letter Phi) with a mathematical value of about 1.618 - also relates to the topology of space-time, and to a biological species ...

Thanks to the more than 11,200 sightings of cetaceans over the course of ten years, Spanish and Portuguese researchers have been able to identify, in detail, the presence of orcas in the Gulf of Cadiz, the Strait of Gibraltar and the Alboran Sea. According to the models that have been generated, the occurrence of these cetaceans is linked to the distribution of their main prey (red tuna) and their presence in Spanish, Portuguese and Moroccan waters is thus more limited than previously thought.

In 2011, the Spanish Ministry of the Environment considered the small population ...

The report was presented in Brussels today at an event held under the auspices of the Italian EU Presidency, gathering over sixty experts in the fields of nuclear physics and medical research.

This document provides an updated overview of how fundamental nuclear physics research has had and will continue to have an impact on developments in medicine.

While most nuclear physics phenomena are far beyond our daily experience there is a great variety of related techniques and applications such as those in medicine which have considerable impact on society. The development ...