Research suggests ability of HIV to cause AIDS is slowing

2014-12-01

(Press-News.org) The rapid evolution of HIV, which has allowed the virus to develop resistance to patients' natural immunity, is at the same time slowing the virus's ability to cause AIDS, according to new research funded by the Wellcome Trust.

The study also indicates that people infected by HIV are likely to progress to AIDS more slowly - in other words the virus becomes less 'virulent' - because of widespread access to antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Both processes make an important contribution to the overall goal of the control and eradication of the HIV epidemic. In 2013, there were a total of 35 million people living with HIV worldwide according to the World Health Organisation.

The study, published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), was led by researchers at the University of Oxford, along with scientists from South Africa, Canada, Tokyo, Harvard University and Microsoft Research.

The research was carried out in Botswana and South Africa, two countries that have been worst affected by the HIV epidemic. Across those countries, researchers enrolled over 2000 women with chronic HIV infection to take part in the study.

The first part of the study looked at whether the interaction between the body's natural immune response and HIV leads to the virus becoming less virulent.

Central to this investigation are proteins in our blood called the human leukocyte antigens (HLA), which enable the immune system to differentiate between the human body's proteins and the proteins of pathogens. People with a gene that expresses a particular HLA protein called HLA-B*57, are known to benefit from a 'protective effect' to HIV. Infected patients with the HLA-B*57 gene progress more slowly than usual to AIDS.

This study showed that in Botswana, where HIV has evolved to adapt to HLA-B*57 more than in South Africa, patients no longer benefit from this gene's protective effect. However, the team's data show that the cost of this adaptation to HIV is that its ability to replicate is significantly reduced, therefore making the virus less virulent.

The authors show that viral adaptation to protective gene variants, such as HLA-B*57, is driving down the virulence of transmitted HIV and is thereby contributing to HIV elimination.

In the second part of the study the authors examined the impact of ART on HIV virulence. They developed a mathematical model, which concluded that selective treatment of people with low CD4 counts will accelerate the evolution of HIV variants with a weaker ability to replicate.

Lead scientist, Professor Phillip Goulder from the University of Oxford, said "This research highlights the fact that HIV adaptation to the most effective immune responses we can make against it comes at a significant cost to its ability to replicate. Anything we can do to increase the pressure on HIV in this way may allow scientists to reduce the destructive power of HIV over time."

Dr Mike Turner, Head of Infection and Immunobiology at the Wellcome Trust said "The widespread use of ART is an important step towards the control of HIV. This research is a good example of how further research into HIV and drug resistance can help scientists to eliminate HIV."

INFORMATION:

Reference

Payne RP. (2014). Impact of HLA-driven HIV Adaptation On Virulence In Populations Of High HIV Seropervalence. PNAS.

Contact

Clare Ryan

Senior Media Officer

T +44 (0)20 7611 7262

M: +44(0)7534 143 849

E c.ryan@wellcome.ac.uk

Elspeth Houlding

Media Assistant

T +44 (0)20 7611 8898

E e.houlding@wellcome.ac.uk

Notes for editors

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to improving health. We provide more than £700 million a year to support bright minds in science, the humanities and the social sciences, as well as education, public engagement and the application of research to medicine.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-12-01

The most commonly used medications for osteoporosis worldwide, bisphosphonates, may also prevent certain kinds of lung, breast and colon cancers, according to two studies led by researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Bisphosphonates had been associated by past studies with slowed tumor growth in some patients but not others, and the mechanism behind these patterns was unknown. In the studies published today, an international research team showed that bisphosphonates ...

2014-12-01

Any science textbook will tell you we can't see infrared light. Like X-rays and radio waves, infrared light waves are outside the visual spectrum.

But an international team of researchers co-led by scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has found that under certain conditions, the retina can sense infrared light after all.

Using cells from the retinas of mice and people, and powerful lasers that emit pulses of infrared light, the researchers found that when laser light pulses rapidly, light-sensing cells in the retina sometimes get a double ...

2014-12-01

INDIANAPOLIS and NEW BRUNSWICK, N.J. -- Imperceptible variations in movement patterns among individuals with autism spectrum disorder are important indicators of the severity of the disorder in children and adults, according to a report presented at the 2014 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in November.

For the first time, researchers at Indiana University and Rutgers University report developing a quantitative way to assess these otherwise ignored variations in movement and link those variations to a diagnosis.

"This is the first time we have been able to explicitly ...

2014-12-01

Two years ago, researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's Joint BioEnergy Institute (JBEI) engineered Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria to convert glucose into significant quantities of methyl ketones, a class of chemical compounds primarily used for fragrances and flavors, but highly promising as clean, green and renewable blending agents for diesel fuel. Now, after further genetic modifications, they have managed to dramatically boost the E.coli's methyl ketone production 160-fold.

"We're encouraged that we could make such a large improvement in methyl ketone ...

2014-12-01

In a remarkable collaborative effort between human and veterinary clinicians, a 29-year-old bottlenose dolphin recently underwent therapeutic bronchoscopy to treat airway narrowing, or stenosis, that was interfering with her breathing. The dolphin, a therapy animal for mentally and physically challenged children at Island Dolphin Care in Key Largo, Florida, is doing well one year after the procedure.

"Many of the medical treatments and procedures used in humans were developed and tested in animals, and many are used in the care of both," said lead author Andrew R. Haas, ...

2014-12-01

MADISON, Wis. -- In 1997, IBM's Deep Blue computer beat chess wizard Garry Kasparov. This year, a computer system developed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison equaled or bested scientists at the complex task of extracting data from scientific publications and placing it in a database that catalogs the results of tens of thousands of individual studies.

"We demonstrated that the system was no worse than people on all the things we measured, and it was better in some categories," says Christopher Ré, who guided the software development for a project while a UW ...

2014-12-01

MADISON, Wis. -- If Brad Singer knew for sure what was happening three miles under an odd-shaped lake in the Andes, he might be less eager to spend a good part of his career investigating a volcanic field that has erupted 36 times during the last 25,000 years. As he leads a large scientific team exploring a region in the Andes called Laguna del Maule, Singer hopes the area remains quiet.

But the primary reason to expend so much effort on this area boils down to one fact: The rate of uplift is among the highest ever observed by satellite measurement for a volcano that ...

2014-12-01

ANN ARBOR--As much as two-thirds of Earth's carbon may be hidden in the inner core, making it the planet's largest carbon reservoir, according to a new model that even its backers acknowledge is "provocative and speculative."

In a paper scheduled for online publication in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this week, University of Michigan researchers and their colleagues suggest that iron carbide, Fe7C3, provides a good match for the density and sound velocities of Earth's inner core under the relevant conditions.

The model, if correct, could help ...

2014-12-01

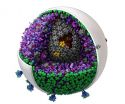

LA JOLLA, CA - December 1, 2014 - Researchers can now explore viruses, bacteria and components of the human body in more detail than ever before with software developed at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI).

In a study published December 1 in the journal Nature Methods, the researchers demonstrated how the software, called cellPACK, can be used to model viruses such as HIV.

"We hope to ultimately increase scientists' ability to target any disease," said Art Olson, professor and Anderson Research Chair at TSRI who is senior author of the new study.

Putting cellPACK ...

2014-12-01

MADISON, Wis. - In 1997, IBM's Deep Blue computer beat chess wizard Gary Kasparov. This year, a computer system developed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison achieved something far more complex. It equaled or bested scientists at the complex task of extracting data from scientific publications and placing it in a database that catalogs the results of tens of thousands of individual studies.

"We demonstrated that the system was no worse than people on all the things we measured, and it was better in some categories," says Christopher Ré, who guided the software ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Research suggests ability of HIV to cause AIDS is slowing