(Press-News.org) Using one of the most powerful lasers in the world, researchers have accelerated subatomic particles to the highest energies ever recorded from a compact accelerator.

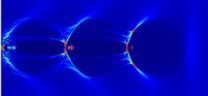

The team, from the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (Berkeley Lab), used a specialized petawatt laser and a charged-particle gas called plasma to get the particles up to speed. The setup is known as a laser-plasma accelerator, an emerging class of particle accelerators that physicists believe can shrink traditional, miles-long accelerators to machines that can fit on a table.

The researchers sped up the particles--electrons in this case--inside a nine-centimeter long tube of plasma. The speed corresponded to an energy of 4.25 giga-electron volts. The acceleration over such a short distance corresponds to an energy gradient 1000 times greater than traditional particle accelerators and marks a world record energy for laser-plasma accelerators.

"This result requires exquisite control over the laser and the plasma," says Dr. Wim Leemans, director of the Accelerator Technology and Applied Physics Division at Berkeley Lab and lead author on the paper. The results appear in the most recent issue of Physical Review Letters.

Traditional particle accelerators, like the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, which is 17 miles in circumference, speed up particles by modulating electric fields inside a metal cavity. It's a technique that has a limit of about 100 mega-electron volts per meter before the metal breaks down.

Laser-plasma accelerators take a completely different approach. In the case of this experiment, a pulse of laser light is injected into a short and thin straw-like tube that contains plasma. The laser creates a channel through the plasma as well as waves that trap free electrons and accelerate them to high energies. It's similar to the way that a surfer gains speed when skimming down the face of a wave.

The record-breaking energies were achieved with the help of BELLA (Berkeley Lab Laser Accelerator), one of the most powerful lasers in the world. BELLA, which produces a quadrillion watts of power (a petawatt), began operation just last year.

"It is an extraordinary achievement for Dr. Leemans and his team to produce this record-breaking result in their first operational campaign with BELLA," says Dr. James Symons, associate laboratory director for Physical Sciences at Berkeley Lab.

In addition to packing a high-powered punch, BELLA is renowned for its precision and control. "We're forcing this laser beam into a 500 micron hole about 14 meters away, " Leemans says. "The BELLA laser beam has sufficiently high pointing stability to allow us to use it." Moreover, Leemans says, the laser pulse, which fires once a second, is stable to within a fraction of a percent. "With a lot of lasers, this never could have happened," he adds.

At such high energies, the researchers needed to see how various parameters would affect the outcome. So they used computer simulations at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) to test the setup before ever turning on a laser. "Small changes in the setup give you big perturbations," says Eric Esarey, senior science advisor for the Accelerator Technology and Applied Physics Division at Berkeley Lab, who leads the theory effort. "We're homing in on the regions of operation and the best ways to control the accelerator."

In order to accelerate electrons to even higher energies--Leemans' near-term goal is 10 giga-electron volts--the researchers will need to more precisely control the density of the plasma channel through which the laser light flows. In essence, the researchers need to create a tunnel for the light pulse that's just the right shape to handle more-energetic electrons. Leemans says future work will demonstrate a new technique for plasma-channel shaping.

INFORMATION:

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world's most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab's scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. For more, visit http://www.lbl.gov. DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://science.energy.gov/.

If you want your child to tell the truth, it's best not to threaten to punish them if they lie. That's what researchers discovered through a simple experiment involving 372 children between the ages of 4 and 8.

How the Experiment was Done

The researchers, led by Prof. Victoria Talwar of McGill's Dept. of Educational and Counselling Psychology, left each child alone in a room for 1 minute with a toy behind them on a table, having told the child not to peek during their absence.

While they were out of the room, a hidden video camera filmed what went on.

When the ...

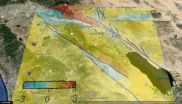

AMHERST, Mass. - New three-dimensional (3D) numerical modeling that captures far more geometric complexity of an active fault segment in southern California than any other, suggests that the overall earthquake hazard for towns on the west side of the Coachella Valley such as Palm Springs and Palm Desert may be slightly lower than previously believed.

New simulations of deformation on three alternative fault configurations for the Coachella Valley segment of the San Andreas Fault conducted by geoscientists Michele Cooke and Laura Fattaruso of the University of Massachusetts ...

Hamilton, ON (Dec. 8, 2014) - Researchers from McMaster University have identified an important hormone that is elevated in obese people and contributes to obesity and diabetes by inhibiting brown fat activity.

Brown adipose tissue, widely known as brown fat, is located around the collarbone and acts as the body's furnace to burn calories. It also keeps the body warm. Obese people have less of it, and its activity is decreased with age. Until now, researchers haven't understood why.

There are two types of serotonin. Most people are familiar with the first type in the ...

Recently, the researchers had constructed several single molecules with dual hormone action. Now, for the first time, the researchers succeeded in designing a substance that combines three metabolically active hormone components (GLP-1, GIP and glucagon) and offers unmatched potency to fight metabolic diseases in pre-clinical trials.

The team headed by physician scientist Matthias Tschöp (Helmholtz Diabetes Center at HMGU and Metabolic Diseases Chair at TUM) and peptide chemist Richard DiMarchi (Indiana University) has been cooperating for almost a decade to invent ...

Harvard Stem Cell Institute researchers at Harvard and Massachusetts General Hospital have taken what they are describing as "the first step toward a pill that can replace the treadmill" for the control of obesity - though it of course would not provide all the additional benefits of exercise.

Chad Cowan, an HSCI Principal Faculty Member and his HSCI team report that they have created a system using human stem cells to screen for compounds that have the potential to turn white, or 'bad', fat cells into brown, or 'good' fat cells, and have already identified two compounds ...

Titan, Saturn's largest moon, is a peculiar place. Unlike any other moon, it has a dense atmosphere. It has rivers and lakes made up of components of natural gas, such as ethane and methane. It also has windswept dunes that are hundreds of yards high, more than a mile wide and hundreds of miles long--despite data suggesting the body to have only light breezes.

Research led by Devon Burr, an associate professor in the Earth and Planetary Sciences Department at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, shows that winds on Titan must blow faster than previously thought to ...

New nanopore DNA sequencing technology on a device the size of a USB stick could be used to diagnose infection - according to new research from the University of East Anglia and Public Health England.

Researchers tested the new technology with a complex problem - determining the cause of antibiotic resistance in a new multi-drug resistant strain of the bacterium that causes Typhoid.

The results, published today in the journal Nature Biotechnology, reveal that the small, accessible and cost effective technology could revolutionise genomic sequencing.

Current technology ...

For a small percentage of cancer patients, treatment aimed at curing the disease leads to a form of leukemia with a poor prognosis. Conventional thinking goes that chemotherapy and radiation therapy induce a barrage of damaging genetic mutations that kill cancer cells yet inadvertently spur the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a blood cancer.

But a new study at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis challenges the view that cancer treatment in itself is a direct cause of what is known as therapy-related AML.

Rather, the research suggests, ...

BOSTON and CAMBRIDGE -- The genetic tumult within cancerous tumors is more than matched by the disorder in one of the mechanisms for switching cells' genes on and off, scientists at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard report in a new study. Their findings, published online today in the journal Cancer Cell, indicate that the disarray in the on-off mechanism - known as methylation - is one of the defining characteristics of cancer and helps tumors adapt to changing circumstances.

The researchers also showed that derangement in ...

BOSTON -- Small cell lung cancer - a disease for which no new drugs have been approved for many years - has shown itself vulnerable to an agent that disables part of tumor cells' basic survival machinery, researchers at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology reported.

In a study published today in the journal Cancer Cell, the investigators found that the agent THZ1 caused human-like small cell lung tumors in mice to shrink significantly, with no apparent side effects. The compound is now being developed into a drug for testing ...