In the course of evolution, animals have become adapted to certain food sources, sometimes even to plants or to fruits that are actually toxic. The driving forces behind such adaptive mechanisms are often unknown. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena, Germany, have now discovered why the fruit fly Drosophila sechellia is adapted to the toxic fruits of the morinda tree. Drosophila sechellia females, which lay their eggs on these fruits, carry a mutation in a gene that inhibits egg production. The flies have very low levels of L-DOPA, a precursor of the hormone dopamine, which controls fertility; interestingly, large amounts of L-DOPA are contained in morinda fruits. Flies that were fed with L-DOPA can compensate for the genetic deficiency and considerably increase their reproductive success. The same gene mutation also contributes to the resistance that these flies have to the toxic acids produced in the fruits and killing all other fruit fly species. (eLife, December 2014)

Drosophila sechellia is a fruit fly species closely related to Drosophila melanogaster. It is endemic to the Seychelles archipelago in the Indian Ocean and a specialist on its only host, Morinda citrifolia. The flies are strongly attracted by the fruits of the morinda tree: they feed on its fruits, and females prefer to lay their eggs on these. Contact with ripe morinda fruits kills other Drosophila species.

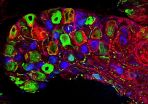

Female Drosophila sechellia flies produce fewer eggs than do other fruit flies. Therefore it is difficult to raise this species in the laboratory. However, if these flies are provided with morinda fruits or chemicals from these fruits, fertility in females increases considerably.

Sofia Lavista Llanos, Bill Hansson and their colleagues at the Department of Evolutionary Neuroethology at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena, Germany, have now found out why Drosophila sechellia is so dependent on the toxic fruits of their host plant. Feeding assays revealed that Drosophila sechellia females produced six times as many eggs when they were fed a diet of morinda fruit instead of the typical laboratory diet.

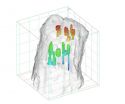

Egg production in the flies is controlled by the hormone dopamine. A dopamine deficiency reduces ovary size and the amount of eggs produced. In Drosophila sechellia, scientists found much lower levels of the precursor compound needed for dopamine biosynthesis than was found in other Drosophila species. This dopamine precursor is L-DOPA, a chemical that is used as a psychoactive drug to treat Parkinson's disease. If L-DOPA is added to their diet, Drosophila sechellia females produce much more eggs than if the drug is not present. This effect is not achieved if dopamine itself is added to the food. The scientists were not too surprised when analyses revealed that morinda contains L-DOPA.

A genetic comparison with other Drosophila species showed that Drosophila sechellia carries a mutation in a gene called Catsup. This mutation inhibits egg production in females. "When we mutated the Catsup gene in the model species Drosophila melanogaster, the mutant flies showed the same characteristics as Drosophila sechellia: They produced fewer eggs and accumulated an enzyme which makes L-DOPA inside their developing eggs," explains Sofia Lavista Llanos. On the other hand, the Catsup mutation provides Drosophila sechellia with an increased resistance to the toxic acids of the morinda fruit. In Drosophila sechellia early resistance is partly achieved by the fact that the Catsup mutation makes the flies ovoviviparous, which means that females lay advanced embryos with a protective skin (cuticle) that shields the offspring from the toxic environment of their host plant. The Catsup mutation is also responsible for the bigger size of Drosophila sechellia embryos, which are almost three times as big as the embryos of other drosophilids. The scientists showed that this increases their hatchability on morinda, probably as a result of the augmented buffering capacity of the embryos.

Fruit flies are usually attracted by low levels of fruity odors, yet highly concentrated odors are repulsive to them. This is not true for Drosophila sechellia: "As we showed in earlier studies, these flies show a persistent attraction to extremely high concentrations of morinda odors without being repulsed," says Bill Hansson. The scientists showed that feeding dopamine to vulnerable fruit fly species helped them cope with the toxic effects of morinda. Now they want to find out if dopamine also influences the strong attraction that Drosophila sechellia shows towards its only host.

The enzymes involved in the dopamine synthesis are conserved across species boundaries in invertebrates and vertebrates. "Drosophila sechellia could serve as a useful genetic model organism in which to study dopamine metabolism. Its close relationship to Drosophila melanogaster is a great advantage, because it provides over 50 years of accumulated knowledge," says Sofia Lavista Llanos. The etiology and effects of dopamine deficiency are of particular interest in medical research: Dopamine is an important neurotransmitter and controls physiological processes, also in humans. Low levels of the "pleasure" hormone dopamine result in fatigue and depression. Patients with Parkinson's disease also suffer from very low dopamine levels. Fundamental knowledge of the genetic and biochemical processes associated with L-DOPA deficiency in Drosophila sechellia may also contribute to understanding dopamine metabolism in humans. [AO]

INFORMATION:

Original Publication:

Lavista Llanos, S., Svatoš, A., Kai, M., Riemensperger, T., Birman, S., Stensmyr, M. C., Hansson, B. S. (2014). Dopamine drives Drosophila sechellia adaptation to its toxic host. eLife 2014;3:e03785, DOI: 10.7554/eLife.03785

http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.03785

Further Information:

Dr. Sofia Lavista Llanos, Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, Hans-Knöll-Straße 8, 07745 Jena, Germany, Tel. +49 3641 57- 1465, E-Mail slavista-llanos@ice.mpg.de

Prof. Dr. Bill S. Hansson, Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, Hans-Knöll-Straße 8, 07745 Jena, Germany, Tel. +49 3641 57- 1401, E-Mail hansson@ice.mpg.de

Picture Requests:

Angela Overmeyer M.A., Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, Hans-Knöll-Str. 8, 07743 Jena, +49 3641 57-2110, overmeyer@ice.mpg.de

Download of high resolution images via http://www.ice.mpg.de/ext/735.html