(Press-News.org) Yeast cells can sometimes reverse the protein misfolding and clumping associated with diseases such as Alzheimer's, according to new research from the University of Arizona.

The new finding contradicts the idea that once prion proteins have changed into the shape that aggregates, the change is irreversible.

"It's believed that when these aggregates arise that cells cannot get rid of them," said Tricia Serio, UA professor and head of the department of molecular and cellular biology. "We've shown that's not the case. Cells can clear themselves of these aggregates."

Prions are proteins that change into a shape that triggers their neighbors to change, also. In that new form, the proteins cluster. The aggregates, called amyloids, are associated with diseases including Alzheimer's, Huntington's and Parkinson's.

"The prion protein is kind of like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde," said Serio, senior author of the paper published today in the open-access journal eLife. "When you get Hyde, all the prion protein that gets made after that is folded in that bad way."

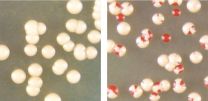

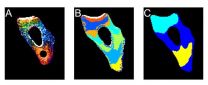

For yeast, having clumps of amyloid is not fatal. Serio and her students exposed amyloid-containing cells of baker's yeast to 104 F (40 C), a temperature that would be a high fever in a human. When exposed to that environment, the cells activated a stress response that changed the clumping proteins back to the no-clumping shape.

The finding suggests artificially inducing stress responses may one day help develop treatments for diseases associated with misfolded prion proteins, Serio said.

"People are trying to develop therapeutics that will artificially induce stress responses," she said. "Our work serves as a proof of principal that it's a fruitful path to follow."

First author on the paper "Spatial quality control bypasses cell-based limitations on proteostasis to promote prion curing" is Serio's former graduate student Courtney Klaips, now at the Max Planck Institute for Biochemistry in Munich. The other authors are Serio's students Megan Hochstrasser, now at the University of California, Berkeley, and Christine Langlois of Brown University. The paper is available here: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.04288

National Institute of Health grants R01 GM069802001, F31 AG034754 and F31 GM099383 funded the research.

To accomplish their jobs inside cells, proteins must fold into specific shapes. Cells have quality-control mechanisms that usually keep proteins from misfolding. However, under some environmental stresses, those mechanisms break down and proteins do misfold, sometimes forming amyloids.

Cells respond to environmental stress by making specific proteins, known as heat-shock proteins, which are known to help prevent protein misfolding.

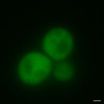

Serio and her students wanted to know whether particular heat-shock proteins could make amyloids revert to the normal shape. To that end, the team studied yeast cells that seemed unable to clear themselves of the amyloid form of the prion protein Sup35.

The researchers were testing one heat-shock protein at a time in an attempt to figure out which particular proteins were needed to clear the amyloids. However, the results weren't making sense, she said.

So she and Klaips decided to stress yeast cells by exposing them to a range of elevated temperatures - as much as 104 F (40 C) - and let the cells do what comes naturally.

As a result, the cells made a battery of heat-shock proteins. The researchers found at one specific stage of the cell's reproductive cycle, the yeast could turn aggregates of Sup35 back into the non-clumping form of the protein.

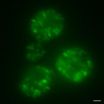

Yeast cells reproduce by budding. The mother cell partitions off a bit of itself into a much smaller daughter cell, which separates and then grows up.

The researchers found in the heat-stressed yeast, just when the daughter was being formed, the mother cell retained most of the heat-shock proteins called chaperones, especially Hsp-104. As a result, the mother had a particularly high concentration of Hsp-104 because little of the protein was shared with the daughter.

The mother cells ended up "curing" themselves of the Sup35 amyloid, although the daughters did not. The degree of curing was correlated with the concentration of Hsp-104 in the cell, and the higher the temperature the more Hsp-104 the cells had.

The Hsp-104 takes the protein in the amyloid and refolds it, Serio said. But she and her colleagues found that just inducing high levels of Hsp-104 in cells by itself does not change the amyloid protein back to the non-clumping form.

"Clearly the heat-shock proteins are collaborating in some way that we don't understand," she said.

Having the amyloid-forming version of the protein is not automatically bad, she said. It may be that shape is good under some environmental conditions, whereas the non-aggregating form is good under others.

Even in humans, amyloid forms of a protein can be helpful, she said. Amyloid proteins are associated with skin pigmentation and with hormone storage.

To clear the amyloid from yeast cells, these experiments triggered cells to make many different heat-shock proteins.

Serio now wants to figure out the minimal system necessary to clear amyloids from a cell. Knowing that may help the development of drug therapies for amyloid-related human diseases, she said.

INFORMATION:

Researcher Contact

Tricia Serio

tserio@email.arizona.edu

520-621-7563

Tricia Serio's website: http://mcb.arizona.edu/people/tserio

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Thinking you're good at math and actually being good at it are not the same thing, new research has found.

About one in five people who say they are bad at math in fact score in the top half of those taking an objective math test. But one-third of people who say they are good at math actually score in the bottom half.

"Some people mis-categorize themselves. They really don't know how good they are when faced with a traditional math test," said Ellen Peters, co-author of the study and professor of psychology at The Ohio State University.

The results ...

GAINESVILLE, Fla. --- Mathematical models predicted it, and now a University of Florida study confirms it: Immunizing school-aged children from flu can protect other segments of the population, as well.

When half of 5- to 17-year-old children in Alachua County were vaccinated through a school-based program, the entire age group's flu rates decreased by 79 percent. Strikingly, the rate of influenza-like illness among 0-4 year olds went down 89 percent, despite the fact that this group was not included in the school-based vaccinations. Among all non-school-aged residents, ...

Supplemental ultrasound screening for all U.S. women with dense breasts would substantially increase healthcare costs with little improvement in overall health, according to senior author Anna Tosteson, ScD, at Dartmouth Hitchcock's Norris Cotton Cancer Center and The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice.

In a study released Monday in the Annals of Internal Medicine, Tosteson and colleagues, including lead author Brian Sprague, MD, provide evidence on the benefits and harms of adding ultrasound to breast cancer screening for women who have had a ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- When a large protein unfolds in transit through a cell, it slows down and can get stuck in traffic. Using a specialized microscope -- a sort of cellular traffic camera -- University of Illinois chemists now can watch the way the unfolded protein diffuses.

Studying the relationship between protein folding and transport could provide great insight into protein-misfolding diseases such as Alzheimer's and Huntington's. Chemistry professor Martin Gruebele and graduate students Minghao Guo and Hannah Gelman published their findings in the journal PLOS ONE.

"We're ...

Irvine, Calif., Dec. 9, 2014 -- A learning technique that maximizes the brain's ability to make and store memories may help overcome cognitive issues seen in fragile X syndrome, a leading form of intellectual disability, according to UC Irvine neurobiologists.

Christine Gall, Gary Lynch and colleagues found that fragile X model mice trained in three short, repetitious episodes spaced one hour apart performed as well on memory tests as normal mice. These same fragile X rodents performed poorly on memory tests when trained in a single, prolonged session - which is a standard ...

A new study links ADHD and conduct disorder in young adolescents with increased alcohol and tobacco use. The Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center study is among the first to assess such an association in this age group.

Conduct disorder is a behavioral and emotional disorder marked by aggressive, destructive or deceitful behavior.

The study is published in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence.

"Early onset of substance abuse is a significant public health concern," says William Brinkman, MD, a pediatrician at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center ...

INDIANAPOLIS -- As hospice for nursing home patients grows dramatically, a new study from the Regenstrief Institute and the Indiana University Center for Aging Research compares the characteristics of hospice patients in nursing homes with hospice patients living in the community. The study also provides details on how hospice patients move in and out of these two settings.

Longer lengths of hospice care, rising costs and concerns over possible duplication of services have led to increased scrutiny by policymakers of hospice patients living in nursing homes. Nursing ...

E-cigarettes appear to be less addictive than cigarettes for former smokers and this could help improve understanding of how various nicotine delivery devices lead to dependence, according to researchers.

"We found that e-cigarettes appear to be less addictive than tobacco cigarettes in a large sample of long-term users," said Jonathan Foulds, professor of public health sciences and psychiatry, Penn State College of Medicine.

The popularity of e-cigarettes, which typically deliver nicotine, propylene glycol, glycerin and flavorings through inhaled vapor, has increased ...

PHILADELPHIA -Researchers at Penn Medicine, in collaboration with a multi-center international team, have shown that a protease inhibitor, simeprevir, a once a day pill, along with interferon and ribavirin has proven as effective in treating chronic Hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) as telaprevir with interferon and ribavirin, the standard of care in developing countries. Further, simeprevir proved to be simpler for patients and had fewer adverse events. The complete study is now available online and is scheduled to publish in January 2015 in The Lancet Infectious Diseases. ...

BELLINGHAM, Washington, USA, and COLCHESTER, UK -- Swimmers looking to monitor and improve technique and patients striving to heal injured muscles now have a new light-based tool to help reach their goals. A research article by scientists at the University of Essex in Colchester and Artinis Medical Systems published today (5 December) in the Journal of Biomedical Optics (JBO) describes the first measurements of muscle oxygenation underwater and the development of the enabling technology.

The article, "Underwater near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy measurements of muscle ...