(Press-News.org) INDIANAPOLIS -- How do some proteins survive the extreme heat generated when they catalyze reactions that can happen as many as a million times per second? Work by researchers from Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) and the University of California Berkeley published online on Dec. 10 in Nature provides an explosive answer to this important question.

Proteins are essential to the human body, doing the bulk of the work within cells. Proteins are large molecules responsible for the structure, function, and regulation of tissues and organs. Enzymes -- special proteins that catalyze chemical reactions within cells -- are critical to every bodily function from breathing to walking. Some enzymes produce a lot of heat per reaction. Enough heat, in fact, that if that heat were to be injected in another protein, that protein would overheat and unfold. So, how do enzymes expel that heat without overheating and self-destructing?

Steve Pressé, Ph.D., assistant professor of physics in the School of Science at IUPUI, led the study's theoretical arm. He is co-corresponding author of the Nature study by Riedel et al. along with Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator Carlos Bustamante, Ph.D., of the University of California Berkley, who led the experimental research arm of the study in close collaboration with Susan Marqusee, M.D., Ph.D., also of UC Berkeley.

"A critical goal in improving human health will be to understand how a protein recovers from a reaction and, ultimately, how to speed up its activity," said Pressé, a biophysicist at IUPUI.

"We have discovered a key fact that explains how enzymes recover from a reaction: enzymes dissipate heat by very rapidly accelerating immediately following the reaction. This finding has very deep implications regarding how heat flows in living systems."

To illustrate how this heat transfer appears to occur, Pressé refers to an observation made by Alexander Graham Bell in the 19th century, which lead to the discovery of the 'photoacoustic effect'. Noting that metal -- when exposed to sun then to shade -- emitted a ringing sound, Bell concluded that heat from light expanded the metal that then recontracted in the shade. In doing so, the metal sent audible pressure waves out into the air.

Similarly, Pressé explains, enzymes respond to the energy released during catalytic reactions by expanding and contracting which in turn violently propels the enzyme and generates a pressure wave -- the study authors call it a chemoacoustic wave -- because it is caused by the heat of a chemical reaction.

"Think of proteins as stepping on landmines. We asked how does a protein avoid damage from the enormous amounts of heat released and not break apart? Now we have shown that they cope with this heat assault by pushing that energy outwards from the reaction site as chemoacoustic waves and propelling themselves away in the meanwhile," said Pressé.

The Pressé, Bustamante and Marqusee labs plan to continue investigating this puzzling 'chemoacoustic effect' on a number of other proteins using a variety of experimental and theoretical methods.

INFORMATION:

The Nature paper is entitled "The Heat Released During Catalytic Turnover Enhances the Diffusion Of An Enzyme." In addition to Bustamante, Pressé and Marqusee authors are Konstantinos Tsekouras, Ph.D., of IUPUI as well as C. Riedel, Ph.D.; R. Gabizon, Ph.D., and K.M. Hamadani, Ph.D., from UC Berkeley and C.A.M. Wilson, Ph.D. from Universidad de Chile.

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Energy, and the National Science Foundation.

The School of Science at IUPUI is committed to excellence in teaching, research and service in the biological, physical, behavioral and mathematical sciences. The school is dedicated to being a leading resource for interdisciplinary research and science education in support of Indiana's effort to expand and diversify its economy.

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Nitrous oxide (N2O) is an important greenhouse gas that doesn't receive as much notoriety as carbon dioxide or methane, but a new study confirms that atmospheric levels of N2O rose significantly as the Earth came out of the last ice age and addresses the cause.

An international team of scientists analyzed air extracted from bubbles enclosed in ancient polar ice from Taylor Glacier in Antarctica, allowing for the reconstruction of the past atmospheric composition. The analysis documented a 30 percent increase in atmospheric nitrous oxide concentrations ...

In a ground-breaking paper published in Nature, they show that the three protein complexes act in relay to regulate cell division: reactivation of one leads to the second becoming active.

Cells rely on control systems to make sure that each aspect of the cell division cycle occurs in the correct order. Following successful segregation of the genomes in mitosis, each must return to its pre-division state in a process called mitotic exit. Mitotic exit is irreversible for all multicellular organisms. Loss of cell cycle control during this process - leading to unregulated ...

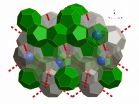

Clathrates are now known to store enormous quantities of methane and other gases in the permafrost as well as in vast sediment layers hundreds of metres deep at the bottom of the ocean floor. Their potential decomposition could therefore have significant consequences for our planet, making an improved understanding of their properties a key priority.

In a paper published in Nature this week, scientists from the University of Göttingen and the Institut Laue Langevin (ILL) report on the first empty clathrate of this type, consisting of a framework of water molecules ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Using a gene-editing system originally developed to delete specific genes, MIT researchers have now shown that they can reliably turn on any gene of their choosing in living cells.

This new application for the CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing system should allow scientists to more easily determine the function of individual genes, according to Feng Zhang, the W.M. Keck Career Development Professor in Biomedical Engineering in MIT's Departments of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and Biological Engineering, and a member of the Broad Institute and MIT's McGovern Institute ...

Anticipated changes in climate will push West Coast marine species from sharks to salmon northward an average of 30 kilometers per decade, shaking up fish communities and shifting fishing grounds, according to a new study published in Progress in Oceanography.

The study suggests that shifting species will likely move into the habitats of other marine life to the north, especially in the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea. Some will simultaneously disappear from areas at the southern end of their ranges, especially off Oregon and California.

"As the climate warms, the species ...

For the firefighters and rescue workers conducting the rescue and cleanup operations at Ground Zero from September 2001 to May 2002, exposure to hazardous airborne particles led to a disturbing "WTC cough" -- obstructed airways and inflammatory bronchial hyperactivity -- and acute inflammation of the lungs. At the time, bronchoscopy, the insertion of a fiber optic bronchoscope into the lung, was the only way to obtain lung samples. But this method is highly invasive and impractical for screening large populations.

That motivated Prof. Elizabeth Fireman of Tel Aviv University's ...

There are pros and cons to the support that victimized teenagers get from their friends. Depending on the type of aggression they are exposed to, such support may reduce youth's risk for depressive symptoms. On the other hand, it may make some young people follow the delinquent example of their friends, says a team of researchers from the University of Kansas in the US, led by John Cooley. Their findings are published in Springer's Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment.

Adolescence is an important time during which youth establish their social identity. ...

Patients with heart disease who receive transfusions during surgeries do just as well with smaller amounts of blood and face no greater risk of dying from other diseases than patients who received more blood, according to a new Rutgers study.

The research, published in the journal Lancet, measures overall mortality and mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer and severe infection, and offers new validation to a recent trend toward smaller transfusions.

For the study, led by Jeffrey Carson, chief of the Division of Internal Medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson ...

A class of drug for treating arthritis - all but shelved over fears about side effects - may be given a new lease of life, following the discovery of a possible way to identify which patients should avoid using it.

The new study, led by Imperial College London and published in the journal Circulation, sheds new light on the 10-year-old question of how COX-2 inhibitors - a type of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) - can increase the risk of heart attack in some people.

NSAIDs - which include very familiar drugs such as ibuprofen, diclofenac and aspirin - are ...

Typhoon Hagupit soaked the Philippines, and a NASA rainfall analysis indicated the storm dropped almost 19 inches in some areas. After Hagupit departed the Philippines as a tropical storm, NASA's Terra satellite passed over and captured a picture of the storm curled up like a cat waiting to pounce when it landfalls in Vietnam on Dec. 11.

The Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission or TRMM satellite, managed by NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency gathered over a week of rainfall data on Hagupit. That rainfall data along with data from other satellites was compiled ...