(Press-News.org) The dragonfly is a swift and efficient hunter. Once it spots its prey, it takes about half a second to swoop beneath an unsuspecting insect and snatch it from the air. Scientists at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Janelia Research Campus have used motion-capture techniques to track the details of that chase, and found that a dragonfly's movement is guided by internal models of its own body and the anticipated movement of its prey. Similar internal models are used to guide behavior in humans.

"This highlights the role that internal models play in letting these creatures construct such a complex behavior," says Janelia group leader Anthony Leonardo, who led the study. "It starts to reshape our view of the neural underpinnings of this behavior." Leonardo, postdoctoral fellows Matteo Mischiati and Huai-Ti Lin, and their colleagues published the findings in the December 11, 2014, issue of the journal Nature.

"Until now, this type of complex control, which incorporates both prediction and reaction, had been demonstrated only in vertebrates," writes Harvard University biologist Stacey A. Combes in an accompanying News & Views perspective in Nature. "However, Mischiati et al. show that dragonflies on the hunt perform internal calculations every bit as complex as those of a ballet dancer."

Neuroscientists have learned a lot about how the nervous system triggers actions in response to sensory information by studying simple reflexive behaviors, such as how an animal escapes a predator. Leonardo has been studying prey capture in dragonflies because he wants to know whether the same stimulus-response loops that researchers have uncovered in those systems also underlie more complex behaviors.

In humans, the simple act of reaching for an object demands sophisticated information processing, Leonardo says. Just to pick up a cup of coffee, the brain calls on a number of internal models. "You have an internal model of how your arm works, how the joints are articulated, of the cup and its mass. If the cup is filled with coffee, you incorporate that," he explains. "Articulating a body and moving it through space is a very complicated problem."

Scientists had so far thought of prey capture by insects as a straightforward system in which a predator's movement is guided solely by the position its prey. "The idea was the dragonfly roughly knows where the prey is relative to him, and he tries to hold this angle constant as he moves toward the interception point. This is the way guided missiles work and how people catch footballs," Leonardo says. But there was reason to believe prey capture was more complicated.

"You don't need a spectacularly complicated model to guess where the prey will be a short time in the future," he says. "But how do you maneuver your body to reach the point of contact?"

In search of a more complete picture, Leonardo and his team spent several years devising a system that allows them to track a dragonfly's body movements as it intercepts its prey. Their strategy is based on the same motion-capture technology used to translate actors' movements into computer animation: reflective markers are placed on different body parts - in this case, the head, body, and wings - and a high-speed video camera records flashes of light reflected from each marker as the insect moves. Using the position of each flash of light, the scientists can reconstruct an outline of the dragonfly as it flies (the accuracy of the outline depends on the number of markers attached to the dragonfly).

Leonardo and his colleagues recorded dragonflies' movements as they chased after either a fruit fly or an artificial prey - a bead maneuvered by a pulley system - whose movements the scientists could precisely control. They focused on following the orientation of the dragonfly's head and body. "That tells us what the dragonfly sees and how its body moves," he explains.

When they analyzed their videos, it was clear that the dragonflies were not simply responding to the movements of the prey. Instead, they made structured turns that adjusted the orientation of their bodies - even when their prey's trajectory did not change. "Those turns were driven by the dragonfly's internal representation of its body and the knowledge that it has to rotate its body and line it up to the prey's flight path in a particular way," Leonardo says.

The dragonflies always aligned themselves so that they would intercept their prey from below, reducing the risk of detection. "At the end of the chase, the fly makes a basket out its legs and the prey drops into it," Leonardo says.

Those shifts in orientation create a challenge for the predator. "The dragonfly is making a lot of turns to line itself up. Those turns create a lot of apparent prey motion. If the whole world is going to spin, how can it possibly see its prey?" Leonardo asks. Surprisingly, the scientists found that each dragonfly moved its head to keep the image of its prey centered on the eye, despite the rotation of its own body. The head movements happened too fast to be a reaction to visual disturbances created by the rotation of the dragonfly's body, Leonardo says. Instead, the head movements must be planned based on the insect's predictions about how to stabilize the image of its prey.

Leonardo says the movements his team observed are so fine-tuned that they keep the image of the prey fixed in the crosshairs of the dragonfly's eyes--their area of greatest acuity--during the duration of the chase. That allows the dragonfly to receive two channels of information about its prey, Leonardo says. The angle between the head and the body tracks the predicted movement of the prey, while the visual system detects any unexpected movement when the prey strays from its position in the crosshairs. "It gives the dragonfly a very elegant combination of predicted model-driven control and the original reactive control," he says.

INFORMATION:

INDIANAPOLIS -- How do some proteins survive the extreme heat generated when they catalyze reactions that can happen as many as a million times per second? Work by researchers from Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) and the University of California Berkeley published online on Dec. 10 in Nature provides an explosive answer to this important question.

Proteins are essential to the human body, doing the bulk of the work within cells. Proteins are large molecules responsible for the structure, function, and regulation of tissues and organs. Enzymes ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Nitrous oxide (N2O) is an important greenhouse gas that doesn't receive as much notoriety as carbon dioxide or methane, but a new study confirms that atmospheric levels of N2O rose significantly as the Earth came out of the last ice age and addresses the cause.

An international team of scientists analyzed air extracted from bubbles enclosed in ancient polar ice from Taylor Glacier in Antarctica, allowing for the reconstruction of the past atmospheric composition. The analysis documented a 30 percent increase in atmospheric nitrous oxide concentrations ...

In a ground-breaking paper published in Nature, they show that the three protein complexes act in relay to regulate cell division: reactivation of one leads to the second becoming active.

Cells rely on control systems to make sure that each aspect of the cell division cycle occurs in the correct order. Following successful segregation of the genomes in mitosis, each must return to its pre-division state in a process called mitotic exit. Mitotic exit is irreversible for all multicellular organisms. Loss of cell cycle control during this process - leading to unregulated ...

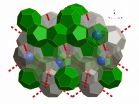

Clathrates are now known to store enormous quantities of methane and other gases in the permafrost as well as in vast sediment layers hundreds of metres deep at the bottom of the ocean floor. Their potential decomposition could therefore have significant consequences for our planet, making an improved understanding of their properties a key priority.

In a paper published in Nature this week, scientists from the University of Göttingen and the Institut Laue Langevin (ILL) report on the first empty clathrate of this type, consisting of a framework of water molecules ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Using a gene-editing system originally developed to delete specific genes, MIT researchers have now shown that they can reliably turn on any gene of their choosing in living cells.

This new application for the CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing system should allow scientists to more easily determine the function of individual genes, according to Feng Zhang, the W.M. Keck Career Development Professor in Biomedical Engineering in MIT's Departments of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and Biological Engineering, and a member of the Broad Institute and MIT's McGovern Institute ...

Anticipated changes in climate will push West Coast marine species from sharks to salmon northward an average of 30 kilometers per decade, shaking up fish communities and shifting fishing grounds, according to a new study published in Progress in Oceanography.

The study suggests that shifting species will likely move into the habitats of other marine life to the north, especially in the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea. Some will simultaneously disappear from areas at the southern end of their ranges, especially off Oregon and California.

"As the climate warms, the species ...

For the firefighters and rescue workers conducting the rescue and cleanup operations at Ground Zero from September 2001 to May 2002, exposure to hazardous airborne particles led to a disturbing "WTC cough" -- obstructed airways and inflammatory bronchial hyperactivity -- and acute inflammation of the lungs. At the time, bronchoscopy, the insertion of a fiber optic bronchoscope into the lung, was the only way to obtain lung samples. But this method is highly invasive and impractical for screening large populations.

That motivated Prof. Elizabeth Fireman of Tel Aviv University's ...

There are pros and cons to the support that victimized teenagers get from their friends. Depending on the type of aggression they are exposed to, such support may reduce youth's risk for depressive symptoms. On the other hand, it may make some young people follow the delinquent example of their friends, says a team of researchers from the University of Kansas in the US, led by John Cooley. Their findings are published in Springer's Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment.

Adolescence is an important time during which youth establish their social identity. ...

Patients with heart disease who receive transfusions during surgeries do just as well with smaller amounts of blood and face no greater risk of dying from other diseases than patients who received more blood, according to a new Rutgers study.

The research, published in the journal Lancet, measures overall mortality and mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer and severe infection, and offers new validation to a recent trend toward smaller transfusions.

For the study, led by Jeffrey Carson, chief of the Division of Internal Medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson ...

A class of drug for treating arthritis - all but shelved over fears about side effects - may be given a new lease of life, following the discovery of a possible way to identify which patients should avoid using it.

The new study, led by Imperial College London and published in the journal Circulation, sheds new light on the 10-year-old question of how COX-2 inhibitors - a type of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) - can increase the risk of heart attack in some people.

NSAIDs - which include very familiar drugs such as ibuprofen, diclofenac and aspirin - are ...