(Press-News.org) Origami is capable of turning a simple sheet of paper into a pretty paper crane, but the principles behind the paper-folding art can also be applied to making a microfluidic device for a blood test, or for storing a satellite's solar panel in a rocket's cargo bay.

A team of University of Pennsylvania researchers is turning kirigami, a related art form that allows the paper to be cut, into a technique that can be applied equally to structures on those vastly divergent length scales.

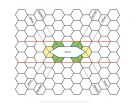

In a new study, the researchers lay out the rules for folding and cutting a hexagonal lattice into a wide variety of useful three-dimensional shapes. Because these rules ensure the proportions of the hexagons remain intact after the cuts and folds are made, the rules apply to starting materials of any size. This enables materials to be selected based on their relevance to the ultimate application, whether it is in nanotechnology, architecture or aerospace.

The study was conducted by Toen Castle, a postdoctoral researcher in the School of Arts & Science's Department of Physics and Astronomy; Shu Yang, a professor in the School of Engineering and Applied Science's Department of Materials Science and Engineering; and professor Randall Kamien, also of the Department of Physics and Astronomy. Also contributing to the study were undergraduate Xingting Gong and postdoctoral researcher Daniel Sussman, members of Kamien's research group; graduate student Euiyeon Jung, a member of Yang's group; and postdoctoral researcher Yigil Cho, who works in both groups.

It was published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

"If you see a fancy piece of origami," Kamien said, "it can have arbitrarily small folds. We want to make something much simpler. If there are standards for the size of folds and cuts, we can make the math apply to any length scale. We can make channels, gates, steps and other 3-D shapes without needing to know anything about the size of the sheet and then combine those building blocks into even more complex shapes."

A hexagonal lattice may seem like an odd choice for a starting point, but the pattern has advantages over a seemingly simpler tessellation, such as one made from squares.

"The connected centers of the hexagons make triangles," Castle said, "so, if you start with a hexagonal lattice, you get the triangles for free. It's like two lattices in one, whereas if you start with squares, you only get squares."

"Plus," Yang said, "it's easier to fill a space with a hexagonal lattice and move from 2-D to 3-D. That's why you see it in nature, in things like honeycombs."

VIDEO:

Origami is capable of turning a simple sheet of paper into a pretty paper crane, but the principles behind the paper-folding art can also be applied to making a microfluidic...

Click here for more information.

Starting from a flat hexagonal grid on a sheet of paper, the researchers outlined the fundamental cuts and folds that allow the resulting shape to keep the same proportions of the initial lattice, even if some of the material is removed. This is a critical quality for making the transition from paper to materials that might be used in real-world applications.

"You can think of the sheet of paper as a template for a mesh of rods that you can lay on top of it," Castle said. "Alternatively, you can think of the paper as the membrane that attaches to a scaffolding. Both concepts are in the theory from the start; it's just a question of whether you want to build the rods or the material between them."

Having a set of rules that draws on fundamental mathematical principles means the kirigami approach can be applied equally across length scales, and with almost any material.

"The rules we lay out," Kamien said, "tell you how you make the cuts so you only have to fold on straight lines, and so that, when you fold them together, the rods remain the same length and the centers remain the same distance apart. You may have to bend [or put hinges on] some of the rods to make the folds, but you don't have to be able to stretch them. That also means the whole structure remains rigid when you're done folding."

"This means it's just a matter of picking the materials with the properties you want for your application," Yang said. "We can go from nanoscale materials like graphene to materials you would make clothing out of to materials you would see in a space station or satellite."

The rules also guarantee that "modules," basic shapes like channels that can direct the flow of fluids, can be combined into more complex ones. For example, iterating those folds and cuts can produce a ratcheting interface that can lock itself into place at different points. This structural feature could change the volume of a channel or even serve as an actuator for a robot.

Kirigami is particularly attractive for nanoscale applications, where the simplest, most space-efficient shapes are necessary, and self-folding materials would circumvent some of the fabrication challenges inherent in working at such small scales.

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation through its ODISSEI program, the American Philosophical Society and the Simons Foundation.

A CEO's natural sunny disposition can have an impact on the way the market reacts to announcements of company earnings, according to research from the University of British Columbia's Sauder School of Business.

The study shows that leaders' inclinations to express themselves with optimism carries over into their tone when disclosing company performance - a tendency that can create an uptick in stock price.

"Ours is the first study to look at the effect of how managers naturally convey themselves," says Sauder Assistant Professor Jenny Zhang, who co-authored the paper. ...

Senescent cells have a bad-guy reputation when it comes to aging. While cellular senescence - a process whereby cells permanently lose the ability to divide when they are stressed - suppresses cancer by halting the growth of premalignant cells, it is also suspected of driving the aging process. Senescent cells, which accumulate over time, release a continual cascade of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, growth factors and proteases. It is a process that sets up the surrounding tissue for a host of maladies including arthritis, atherosclerosis and late life cancer. But ...

The ascetic and moralizing movements that spawned the world's major religious traditions--Buddhism, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, and Christianity--all arose around the same time in three different regions, and researchers reporting in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on December 11 have now devised a statistical model based on history and human psychology that helps to explain why. The emergence of world religions, they say, was triggered by the rising standards of living in the great civilizations of Eurasia.

"One implication is that world religions and secular spiritualities ...

EMBARGOED for release Thursday, Dec. 11, 2014, at 12 p.m. ET

HOUSTON - (Dec. 11, 2014) - The ancient Japanese art of origami is based on the idea that nearly any design - a crane, an insect, a samurai warrior - can be made by taking the same blank sheet of paper and folding it in different ways.

The human body faces a similar problem. The genome inside every cell of the body is identical, but the body needs each cell to be different -an immune cell fights off infection; a cone cell helps the eye detect light; the heart's myocytes must beat endlessly.

Appearing online ...

Clinical trials to test the new drugs in patients should begin as early as 2015.

Existing drugs target faulty versions of a protein called BRAF which drives about half of all melanomas, but while initially very effective, the cancers almost always become resistant to treatment within a year.

The new drugs - called panRAF inhibitors - could be effective in patients with melanoma who have developed resistance to BRAF inhibitors.

The new study was funded by the Wellcome Trust and Cancer Research UK, and jointly led by scientists at The Institute of Cancer Research, ...

Scientists at the University of Southampton have found that the precise shape of an antibody makes a big difference to how it can stimulate the body's immune system to fight cancer, paving the way for much more effective treatments.

The latest types of treatment for cancer are designed to switch on the immune system, allowing the patient's own immune cells to attack and kill cancerous cells, when normally the immune cells would lie dormant.

In a study, funded by Cancer Research UK and published in the journal Cancer Cell, the Southampton team have found that a particular ...

PHILADELPHIA - (Dec. 11, 2014) - A team of scientists, led by researchers at The Wistar Institute, has found that an infection with herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) causes rearrangements in telomeres, small stretches of DNA that serve as protective ends to chromosomes. The findings, which will be published in the Dec. 24 edition of the journal Cell Reports, show that this manipulation of telomeres may explain how viruses like herpes are able to successfully replicate while also revealing more about the protective role that telomeres play against other viruses.

"We know ...

The saga of the Osedax "bone-eating" worms began 12 years ago, with the first discovery of these deep-sea creatures that feast on the bones of dead animals. The Osedax story grew even stranger when researchers found that the large female worms contained harems of tiny dwarf males.

In a new study published in the Dec. 11 issue of Current Biology, marine biologist Greg Rouse at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego and his collaborators reported a new twist to the Osedax story, revealing an evolutionary oddity unlike any other in the animal kingdom. Rouse's ...

HOUSTON -- (Dec. 11, 2014) -- In a triumph for cell biology, researchers have assembled the first high-resolution, 3-D maps of entire folded genomes and found a structural basis for gene regulation -- a kind of "genomic origami" that allows the same genome to produce different types of cells. The research appears online today in Cell.

A central goal of the five-year project, which was carried out at Baylor College of Medicine, Rice University, the Broad Institute and Harvard University, was to identify the loops in the human genome. Loops form when two bits of DNA that ...

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- Some drugs used to treat diabetes mimic the behavior of a hormone that a University at Buffalo psychologist has learned controls fluid intake in subjects. The finding creates new awareness for diabetics who, by the nature of their disease, are already at risk for dehydration.

Derek Daniels' paper "Endogenous Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Reduces Drinking Behavior and Is Differentially Engaged by Water and Food Intakes in Rats," co-authored with UB psychology graduate students Naomi J. McKay and Daniela L. Galante, appears in this month's edition of the Journal ...