(Press-News.org) BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- Scientists at Indiana University and colleagues at Stanford and the University of Texas have demonstrated a technique for "editing" the genome in sperm-producing adult stem cells, a result with powerful potential for basic research and for gene therapy.

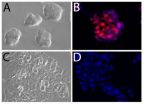

The researchers completed a "proof of concept" experiment in which they created a break in the DNA strands of a mutant gene in mouse cells, then repaired the DNA through a process called homologous recombination, replacing flawed segments with correct ones.

The study involved spermatogonial stem cells, which are the foundation for the production of sperm and are the only adult stem cells that contribute genetic information to the next generation. Repairing flaws in the cells could thus prevent mutations from being passed to future generations.

"We showed a way to introduce genetic material into spermatogonial stem cells that was greatly improved from what had been previously demonstrated," said Christina Dann, associate scientist in the Department of Chemistry at IU Bloomington and a co-author of the study. "This technique corrects the mutation, theoretically leaving no other mark on the genome."

The paper, "Genome Editing in Mouse Spermatogonial Stem/Progenitor Cells Using Engineered Nucleases," was published in the online science journal PLOS-ONE.

The lead author, Danielle Fanslow, carried out the research as an IU research associate and is now a doctoral student at Northwestern University. Additional co-authors are from the Stanford School of Medicine and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

A challenge to the research was the fact that spermatogonial stem cells, like many types of adult stem cells, are notoriously difficult to isolate, culture and work with. It took years of intensive effort by multiple laboratories before conditions were created a decade ago to maintain and propagate the cells.

For the IU research, a primary hurdle was to find a way to make specific, targeted modifications to the mutant mouse gene without the risk of disease caused by random introduction of genetic material. The researchers used specially designed enzymes, called zinc finger nucleases and transcription activator-like effector nucleases, to create a double strand break in the DNA and bring about the repair of the gene.

Stem cells that had been modified in the lab were then transplanted into the testes of sterile mice. The transplanted cells grew or colonized within the mouse testes, indicating the stem cells were viable. However, attempts to breed the mice were not successful.

"Whether the failure to produce sperm was a result of abnormalities in the transplanted cells or the recipient testes was unclear," the researchers write.

In a separate study, published this month in the journal Cell Research, scientists from several institutions in China used a different technology to edit a faulty gene in spermatogonial stem cells of mice. In this study, the mice were able to successfully reproduce following transplantation of the cells carrying the corrected gene.

The research developments could open doors for better understanding of stem cells and advances in gene therapy. The ability to edit the genome could facilitate analysis of gene function and the processes by which sperm cells divide and differentiate. The techniques could be used, for instance, to test the functional importance of a genetic mutation implicated in reproductive failure.

As a medical advance, the studies demonstrate techniques for correcting mutations that are more effective than previous methods. And the fact that they work on spermatogonial stem cells is especially significant. While gene therapy has been effective at treating certain diseases, patients live with the knowledge that they may transmit a genetic condition to their children. Modifying the patients' germ cells could, at some time in the future, address that risk.

INFORMATION:

Patients with Parkinson's, medics and carers have identified the top ten priorities for research into the management of the condition in a study by the University of East Anglia and Parkinson's UK.

Commissioned by Parkinson's UK, people with direct and indirect personal experience of the condition worked together to identify crucial gaps in the existing evidence to address everyday practicalities in the management of the complexities of Parkinson's. Patients stated that the overarching research aspiration was an effective cure for Parkinson's but whilst waiting for this ...

DALLAS - Dec. 15, 2014 - UT Southwestern Medical Center neurology researchers have identified an important cell signaling mechanism that plays an important role in brain cancer and may provide a new therapeutic target.

Researchers found that this mechanism -- a type of signaling termed constitutive or non-canonical epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling -- is highly active in glioblastomas, the most common type of adult brain cancer and a devastating disease with a poor prognosis.

When activated in cancer cells, it protects the tumor cells, making them more ...

In the same way as we now connect computers in networks through optical signals, it could also be possible to connect future quantum computers in a 'quantum internet'. The optical signals would then consist of individual light particles or photons. One prerequisite for a working quantum internet is control of the shape of these photons. Researchers at Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e) and the FOM foundation have now succeeded for the first time in getting this control within the required short time. These findings are published today in Nature Communications.

Quantum ...

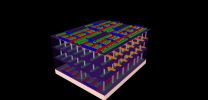

For decades, the mantra of electronics has been smaller, faster, cheaper.

Today, Stanford engineers add a fourth word - taller.

At a conference in San Francisco, a Stanford team will reveal how to build high-rise chips that could leapfrog the performance of the single-story logic and memory chips on today's circuit cards.

Those circuit cards are like busy cities in which logic chips compute and memory chips store data. But when the computer gets busy, the wires connecting logic and memory can get jammed.

The Stanford approach would end these jams by building layers ...

PEOPLE who have problems with numbers may be more likely to feel negative about bowel cancer screening, including fearing an abnormal result, while some think the test is disgusting or embarrassing, according to a Cancer Research UK supported study* published today (Monday) in the Journal of Health Psychology.

The researchers** sent information about bowel cancer screening to patients aged from 45 to 59 along with a questionnaire which assessed their numerical skills and attitudes to the screening test, which looks for blood in stool samples.

Almost 965 people - registered ...

E-cigarette use among teenagers is growing in the U.S., and Hawaii teens take up e-cigarette use at higher rates than their mainland counterparts, a new study by University of Hawaii Cancer Center researchers has found.

The findings come as e-cigarettes grow in popularity and the Food and Drug Administration is considering how to regulate their sale. Some public health officials are concerned that e-cigarettes may be recruiting a new generation of young cigarette smokers who otherwise might not take up smoking at all, and the study's results bolster this position.

Data ...

While serious infections can be transmitted from donated organs, the risk of passing Ebola virus disease from an organ donor to a recipient is extremely small. In a new editorial published in the American Journal of Transplantation, experts explain how simple assessments of donors can help ensure that the organ supply is safe, while having little impact on the donor pool.

Despite screening all organ donors for infection, on rare occasions an organ donor will transmit an unexpected infection to a recipient. Because cases of Ebola virus disease have occurred in the United ...

Both positive and negative experiences influence how genetic variants affect the brain and thereby behaviour, according to a new study. "Evidence is accumulating to show that the effects of variants of many genes that are common in the population depend on environmental factors. Further, these genetic variants affect each other," explained Sheilagh Hodgins of the University of Montreal and its affiliated Institut Universitaire en Santé Mentale de Montréal. "We conducted a study to determine whether juvenile offending was associated with interactions between three ...

Baltimore MD-- We would not expect a baby to join a team or participate in social situations that require sophisticated communication. Yet, most developmental biologists have assumed that young cells, only recently born from stem cells and known as "progenitors," are already competent at inter-communication with other cells.

New research from Carnegie's Allan Spradling and postdoctoral fellow Ming-Chia Lee shows that infant cells have to go through a developmental process that involves specific genes before they can take part in the group interactions that underlie ...

TORONTO, ON - Consider the relationship between an air traffic controller and a pilot. The pilot gets the passengers to their destination, but the air traffic controller decides when the plane can take off and when it must wait. The same relationship plays out at the cellular level in animals, including humans. A region of an animal's genome - the controller - directs when a particular gene - the pilot - can perform its prescribed function.

A new study by cell and systems biologists at the University of Toronto (U of T) investigating stem cells in mice shows, for the ...