Click here for more information.

When you open the refrigerator for a late-night snack, are you more likely to grab a slice of chocolate cake or a bag of carrot sticks? Your ability to exercise self-control--i.e., to settle for the carrots--may depend upon just how quickly your brain factors healthfulness into a decision, according to a recent study by Caltech neuroeconomists.

"In typical food choices, individuals need to consider attributes like health and taste in their decisions," says graduate student Nicolette Sullivan, lead author of the study, which appears in the December 15 issue of the journal Psychological Science. "What we wanted to find out was at what point the taste of the foods starts to become integrated into the choice process, and at what point health is integrated."

Since taste is a concrete, innate attribute--after all, people know what foods they like and do not like--the researchers hypothesized that it becomes factored into the food decision-making process first. A food's affect on health, on the other hand, is a more abstract attribute--one that you often need to learn about or do research on. In fact, there are such widely varying opinions about the healthfulness of nutrients like fats, calories, and carbs that you may not even be able to find a definitive answer. Therefore, the researchers assumed, the healthiness of a food likely is not factored into a person's food choice until after taste is. And for those individuals who exercised less self-control, they hypothesized, health would factor into the choice even later.

To test these ideas, Sullivan--along with her colleagues in the laboratory of Antonio Rangel, Bing Professor of Neuroscience, Behavioral Biology, and Economics, including Rangel himself--developed a new experimental technique that allowed them to evaluate, on a scale of milliseconds, when taste and health information kick in during the process of making a decision. They did this by tracking the movement of a computer mouse as a person makes a choice.

In the experiment, 28 hungry subjects--Caltech student-volunteers who had been fasting for four hours--were asked to rate 160 foods individually on a scale from -2 to 2, based on that food's healthfulness, its tastiness, and how much the subject would like to eat that food after the experiment was over. The subjects were then presented with 280 random pairings of those same foods and were asked to use a computer mouse to click on--to choose--which food they preferred from each pairing.

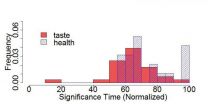

The researchers then used statistical tools to analyze each subject's cursor movements and, therefore, the choice process. They looked at how fast taste began to drive the mouse's movement--and how soon health did. For example, one subject's cursor trajectory might be driven by the taste of the foods very early in the trial, but soon after might be driven by health also--resulting in the selection of the healthier item, like Brussels sprouts over pizza. However, another subject's cursor trajectory might be driven by taste all the way to the selection of pizza--with health information coming online too late in the choice process to influence the selection of the food.

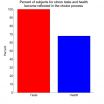

Sullivan and her colleagues found that, on average, taste information began to influence the trajectory of the mouse cursor, and thus the choice process, almost 200 milliseconds earlier than health information. For 32 percent of subjects, health never influenced their food choice at all; they made every single choice based on taste, and their cursor was never driven by the healthfulness of the items.

"What Nikki has shown is that a big factor here is how quickly you can represent and take into account different types of information when you are making choices," says Rangel. "People are making these choices very quickly--in a couple of seconds--so very small differences, even just a hundred milliseconds, can make an enormous difference in whether or how much health considerations ultimately influences the decision."

The researchers then wanted to find out if some people have an advantage in exercising self-control simply because they can factor health information into their choice earlier. Sullivan and her colleagues first split the subjects into two groups: those who exercised high self-control by often choosing the healthy option, and those who made their choices based almost entirely on taste--the low-self-control group.

On average, the low-self-control group began to factor in health information 323 milliseconds later than the high-self-control group. This suggests, says Sullivan, that the more quickly someone begins to consider a food's health benefits, the more likely they are to exert self-control by ultimately choosing the healthier food.

In addition, Sullivan says, it seems that those who calculate health earlier in the process also weigh it more heavily in their decision-making process.

These findings, she notes, mean it might one day be useful to encourage people to wait a bit longer before making a food choice. "Since we know that taste appears before health, we know that it has an advantage in the ultimate decision. However, once health comes online, if you wait--allowing the health information to accumulate for longer--that might give health a chance to catch up and influence the choice," she says.

Rangel adds that this work could also one day change the way health information is presented. "For example, if you go to the supermarket, does it matter how big the calorie count information label is on the yogurt?" he asks. "More visible information may affect how quickly you compute health information. We don't know, but this study opens such possibilities."

Sullivan and Rangel are next hoping to apply their cursor-tracking method to experiments beyond the refrigerator. They want to look, for instance, at how timing might affect self-control in choices involving saving money versus spending money, or deciding between an act of altruism versus an act of selfishness. They also plan to further explore the food-choice study in a larger and more diverse population of subjects through the Caltech Conte Center.

"In the past when psychologists and economists have thought about behavioral differences, they have thought of them as differences in preferences, like, 'Oh you make less healthy choices than her because you just value health less and that's the end of the story.' What our study is trying to say is that maybe part of these differences arise not from preferences, but from the amount of time it takes different people to represent information and feed it to the brain's decision-making circuit."

INFORMATION:

The Psychological Science study, "Dietary Self-Control Is Related to the Speed with Which Health and Taste Attributes Are Processed," was authored by Sullivan and Rangel along with Caltech postdoctoral scholar Cendri Hutcherson and former Caltech postdoctoral scholar and visiting associate Alison Harris, who is now an assistant professor of psychology at Claremont McKenna College. Their work was funded by the National Science Foundation.