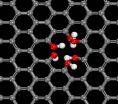

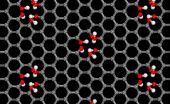

(Press-News.org) The honeycomb structure of pristine graphene is beautiful, but Northwestern University scientists, together with collaborators from five other institutions, have discovered that if the graphene naturally has a few tiny holes in it, you have a proton-selective membrane that could lead to improved fuel cells.

A major challenge in fuel cell technology is efficiently separating protons from hydrogen. In a study of single-layer graphene and water, the Northwestern researchers found that slightly imperfect graphene shuttles protons -- and only protons -- from one side of the graphene membrane to the other in mere seconds. The membrane's speed and selectivity are much better than that of conventional membranes, offering engineers a new and simpler mechanism for fuel cell design.

"Imagine an electric car that charges in the same time it takes to fill a car with gas," said chemist Franz M. Geiger, who led the research. "And better yet -- imagine an electric car that uses hydrogen as fuel, not fossil fuels or ethanol, and not electricity from the power grid, to charge a battery. Our surprising discovery provides an electrochemical mechanism that could make these things possible one day."

Defective single-layer graphene, it turns out, produces a membrane that is the world's thinnest proton channel -- only one atom thick.

"We found if you just dial the graphene back a little on perfection, you will get the membrane you want," said Geiger, a professor of chemistry in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. "Everyone always strives to make really pristine graphene, but our data show if you want to get protons through, you need less perfect graphene."

The study will be published March 17 by the journal Nature Communications.

Geiger's research team included collaborators from Northwestern, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the University of Virginia, the University of Minnesota, Pennsylvania State University and the University of Puerto Rico.

In the atomic world of an aqueous solution, protons are pretty big, and scientists don't believe they can be driven through a single layer of chemically perfect graphene at room temperature. (Graphene is a form of elemental carbon composed of a single flat sheet of carbon atoms arranged in a repeating hexagonal, or honeycomb, lattice.)

When Geiger and his colleagues studied graphene exposed to water, they found that protons were indeed moving through the graphene. Using cutting-edge laser techniques, imaging methods and computer simulations, they set out to learn how.

The researchers discovered that naturally occurring defects in the graphene -- where a carbon atom is missing -- triggers a chemical merry-go-round where protons from water on one side of the membrane are shuttled to the other side in a few seconds. Their advanced computer simulations showed this occurs via a classic "bucket-line" mechanism first proposed in 1806.

The thinness of the atom-thick graphene makes it a quick trip for the protons, Geiger said. With conventional membranes, which are hundreds of nanometers thick, proton selection takes minutes -- much too long to be practical.

Next, the research team asked the question: How many carbon atoms do we need to knock out of the graphene layer to get protons to move through? Just a handful in a square micron area of graphene, the researchers calculated.

Removing a few carbon atoms results in others being highly reactive, which starts the proton shuttling process. Only protons go through the tiny holes, making the membrane very selective. (Conventional membranes are not very selective.)

"Our results will not make a fuel cell tomorrow, but it provides a mechanism for engineers to design a proton separation membrane that is far less complicated than what people had thought before," Geiger said. "All you need is slightly imperfect single-layer graphene."

INFORMATION:

The paper is titled "Aqueous Proton Transfer Across Single-Layer Graphene."

Movie and images are available at https://northwestern.box.com/s/8ud25wrc5u729lxe9unps8dltnbdszzr.

An atomically thin membrane with microscopically small holes may prove to be the basis for future hydrogen fuel cells, water filtering and desalination membranes, according to a group of 15 theorists and experimentalists, including three theoretical researchers from Penn State.

The team, led by Franz Geiger of Northwestern University, tested the possibility of using graphene, the robust single atomic layer carbon, as a separation membrane in water and found that naturally occurring defects, essentially a few missing carbon atoms, allowed hydrogen protons to cross the ...

An analysis of genetic and lifestyle data from 10 large epidemiologic studies confirmed that regular use of aspirin or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) appears to reduce the risk of colorectal cancer in most individuals. The study being published in the March 17 issue of JAMA found that a few individuals with rare genetic variants do not share this benefit. The study authors note, however, that additional questions need to be answered before preventive treatment with these medications can be recommended for anyone.

"Previous studies, including randomized ...

Among approximately 19,000 individuals, the use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) was associated with an overall lower risk of colorectal cancer, although this association differed according to certain genetic variations, according to a study in the March 17 issue of JAMA.

Considerable evidence demonstrates that use of aspirin and other NSAIDs is associated with a lower risk of colorectal cancer. However, the mechanisms behind this association are not well understood. Routine use of aspirin, NSAIDs, or both for prevention of cancer is not currently ...

In a study in which pathologists provided diagnostic interpretation of breast biopsy slides, overall agreement between the individual pathologists' interpretations and that of an expert consensus panel was 75 percent, with the highest level of concordance for invasive breast cancer and lower levels of concordance for ductal carcinoma in situ and atypical hyperplasia, according to a study in the March 17 issue of JAMA.

Approximately 1.6 million women in the United States have breast biopsies each year. The accuracy of pathologists' diagnoses is an important and inadequately ...

Older adults who had spine imaging within 6 weeks of a new primary care visit for back pain had pain and disability over the following year that was not different from similar patients who did not undergo early imaging, according to a study in the March 17 issue of JAMA.

When to image older adults with back pain remains controversial. Many guidelines recommend that older adults undergo early imaging because of the higher prevalence of serious underlying conditions. However, there is not strong evidence to support this recommendation. Adverse consequences of early imaging ...

An additional 18 months of dual antiplatelet therapy among patients who received a bare metal coronary stent did not result in significant differences in rates of stent thrombosis (formation of a blood clot), major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events, or moderate or severe bleeding, compared to patients who received placebo, according to a study in the March 17 issue of JAMA. The authors note that limitations in sample size may make definitive conclusions regarding these findings difficult.

Current clinical practice guidelines recommend a minimum of only 1 month ...

An examination of the reporting of noninferiority clinical trials raises questions about the adequacy of their registration and results reporting within publicly accessible trial registries, according to a study in the March 17 issue of JAMA.

Noninferiority clinical trials are designed to determine whether an intervention is not inferior to a comparator by more than a prespecified difference (known as the noninferiority margin). Selection of an appropriate margin is fundamental to noninferiority trial validity, yet a point of frequent ambiguity. Given the increasing ...

WASHINGTON, D.C., March 17, 2015 - Winter storms dumped records amounts of snow on the East Coast and other regions of the country this February, leaving treacherous, icy sidewalks and roads in their wake. Now researchers from Canada are developing new methods to mass-produce a material that may help pedestrians get a better grip on slippery surfaces after such storms.

The material, which is made up of glass fibers embedded in a compliant rubber, could one day be used in the soles of slip-resistant winter boots. The researchers describe the manufacturing process in a ...

For every parent who ever wondered what the heck their teens were thinking when they posted risky information or pictures on social media, a team of Penn State researchers suggests that they were not really thinking at all, or at least were not thinking like most adults do.

In a study, the researchers report that the way teens learn how to manage privacy risk online is much different than how adults approach privacy management. While most adults think first and then ask questions, teens tend to take the risk and then seek help, said Haiyan Jia, post-doctoral scholar in ...

Large-scale climate patterns that affect the Pacific Ocean indicate that waters off the West Coast have shifted toward warmer, less productive conditions that may affect marine species from seabirds to salmon, according to the 2015 State of the California Current Report delivered to the Pacific Fishery Management Council.

The report by NOAA Fisheries' Northwest Fisheries Science Center and Southwest Fisheries Science Center assesses productivity in the California Current from Washington south to California. The report examines environmental, biological and socio-economic ...