Now, researchers at the University of Iowa have identified a mechanism that dividing cells in worms use to ensure their proper development, and they believe the same process could be going on in humans. The mechanism, unknown until now, describes one part of the cell, called the centrosome, as an "internal timekeeper"--like a train conductor. A crucial protein in charge of gene expression, beta-catenin, is described as a "hitchhiker"--it jumps onboard the cellular train and helps cells grow the way they should.

The researchers believe that the hitchhiker protein attaches to the timekeeping centrosome, only so that it can be properly regulated and divided out in the correct amounts to the newly forming cells.

"The majority of tumors have severe centrosome abnormalities," says UI integrated biology doctoral candidate and first author Setu Vora. "So it's entirely possible that this kind of mechanism at the centrosome may be relevant in human diseases, such as cancer."

The researchers believe their discovery could have implications for cancer research, and lend greater understanding to how we develop.

"We think it's crucial to understand how these basic mechanisms work in order to better understand human development and disease," says Bryan Phillips, UI assistant professor of biology and corresponding author.

The Timekeeper's Mechanism

A key part of all animal cells, the centrosome, acts as the cell division captain--it is responsible for making sure new cells get equal portions of DNA when they are created. Now, the UI researchers say, the centrosome also acts as the timekeeper during cell division, specifically for another crucial member in the process, beta-catenin.

Beta-catenin is a protein that controls gene expression. Basically, it is present during cell division but starts to degrade, limiting how much of itself is given to the daughter cells. How much beta-catenin each cell gets during division helps to determine what kind of cell it is: arm, leg, liver, or otherwise. The researchers found that beta-catenin only knows how much of itself to give out to newly forming cells because it attaches to the centrosome--this is where the centrosome's timekeeper responsibilities come in.

Centrosomes mature and grow inside of cells just as the cells start to divide. It might seem counterintuitive to have a crucial part of a cell become active just before the cell is splitting apart, but it means that a mature centrosome could serve as an internal indicator that the cell is about to divide. At that same moment, beta-catenin attaches itself to the centrosome, like a hitchhiker, Phillips says. Attached, the Timekeeper and the Hitchhiker start to work together.

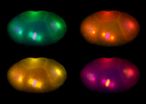

Lab photographs of dividing cells Lab photographs of the dividing cells. The round, sun-like structures in each cell are the centrosomes. The fluorescent-tagged beta-catenin is the singular, oblong structure of contrasting color. Photo courtesy of Bryan Phillips. Because of its hitchhiking ability, the two newly forming daughter cells inherit little beta-catenin. This allows for tight control of the levels of newly formed beta-catenin; one cell can then accumulate low beta-catenin levels, and one high levels. The difference in beta-catenin will dictate what kind of tissue the cells will become. The centrosome, with its eye on the clock, lets this process go on just long enough for the new cells to get as much beta-catenin as each one needs to become the properly functioning tissue it is supposed to be, before the centrosome and beta-catenin detach, and the process ends.

The Method, and Beyond

The researchers were able to track the entire mechanism in their model system, a transparent roundworm called C. elegans. They used a well-known technique to put a fluorescent tag on the beta-catenin proteins into the worm, and they could monitor the process under a fluorescent microscope. The researchers inserted a manipulated piece of DNA into the genome of the worm, consisting of the information that encodes the protein, and also the information that encodes the fluorescent tag. That way, every time the worm produced more of the protein, it showed up as a fluorescent green dot.

Those collections of dots got brighter the more beta-catenin was in one area, and the researchers could measure the intensity of that fluorescent light in each cell with a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera attached to their microscope. That allowed them to not only see that the beta-catenin was attached to the centrosome, but also, how much of it was being produced.

As it turns out, the only reason beta-catenin attaches to the centrosome at all is to be regulated, the researchers say. When they blocked beta-catenin's ability to hitchhike on the centrosome, the daughter cells that were supposed to receive low levels of beta-catenin ended up with too much. Some of those cells end up converting to completely different tissue types.

The study, "Centrosome-Associated Degradation Limits beta-catenin Inheritance by Daughter Cells after Asymmetric Division," presented in April in the journal Current Biology, has implications for the growth of cancer cells, Phillips says.

"In adults, this might be important because we need to keep beta-catenin levels regulated in stem cells. If there is too much beta-catenin in our stem cells, the cells can divide too quickly and may become cancerous," Phillips says.

Beta-catenin regulation is clinically important. Nearly all intestinal tumors involve some measure of beta-catenin regulation defect, and early birth defects involving beta-catenin result in miscarriage. Additionally, beta-catenin helps early embryonic patterning decisions in mammals, including core pathways involved in development of limbs, Phillips says.

Continuing to study the centrosome with the understanding of this mechanism, and how proteins are distributed to new cells, could lead to crucial new medical information. It is a couple steps out from this initial discovery, but the mechanism opens the door to a world of understanding about our cells, Phillips says.

INFORMATION:

The study was funded through a grant from the American Cancer Society and the Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center, a grant from the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust, and an Evelyn Hart Watson fellowship.