Most animals, from roundworms to humans, prefer the more predictable situation when it comes to securing resources for survival, such as food. Now, Salk scientists have discovered the basis for how animals balance learning and risk-taking behavior to get to a more predictable environment. The research reveals new details on the function of two chemical signals critical to human behavior: dopamine--responsible for reward and risk-taking--and CREB--needed for learning.

"Previous research has shown that certain neurons respond to changes in light to determine variability in their environment, but that's not the only mechanism," says senior author Sreekanth Chalasani, an assistant professor in Salk's Molecular Neurobiology Laboratory. "We discovered a new mechanism that evaluates environmental variability, a skill crucial to animals' survival."

By studying roundworms (Caenorhabditis elegans), Salk researchers charted how this new circuit uses information from the animal's senses to figure out how predictable the environment and prompt the worm to move to a new location if needed. The work was detailed April 9, 2015 in Neuron.

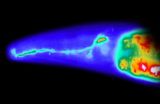

The circuit, made up of 16 of the 302 neurons in the worm's brain, likely has parallels in more complex animal brains, researchers say, and could be a starting point to understanding--and fixing--certain psychiatric or behavioral disorders.

"What was surprising is the degree to which variability in animal behavior can be explained by variability in their past sensory experience and not just noise," says Tatyana Sharpee, associate professor and co-senior author of the paper. "We can now predict future animal behaviors based on past sensory experience, independent of the influence of genetic factors."

The team discovered that two pairs of neurons in this learning circuit act as gatekeepers. One pair responds to large increases of the presence of food and the other pair responds to large decreases of the presence of food. When either of these high-threshold neurons detect a large change in an environment (for example, the smell of a lot of food to no food) they induce other neurons to release the neurotransmitter dopamine.

Dumping dopamine onto a brain--human or otherwise--makes one more willing to take risks. It's no different in the roundworm: stimulated by large varieties in its environment, dopamine surges in the worm's system and activates four other neurons in the learning circuit, giving them a greater response range. This prompts the worm to search more actively in a wider area (risk-taking) until it hits a more consistent environment. The amount of dopamine in its system serves as its memory of the past experience: about 30 minutes or so and it forgets information gathered in the time before that.

While it's been known that the presence of dopamine is tied to risk-taking behavior, how exactly dopamine does this hasn't been well understood. With this new work, scientists now have a fundamental model of how dopamine signaling leads the worm to take more risks and explore new environments.

"The connection between dopamine and risk is conserved across animals and is already known, but we showed mechanistically how it works," says Chalasani, who is also holder of the Helen McLoraine Developmental Chair in Neurobiology. "We hope this work will lead to better therapies for neurodegenerative and behavioral diseases and other disorders where dopamine signaling is irregular."

Interestingly, the scientists found that the high-threshold neurons also lead to increased signaling from a protein called CREB, known in humans and other animals to be essential to learning and retaining new memories. The researchers showed that not only are the presence of CREB important to learning, but the amount of CREB protein determines how quickly an animal learns. This surprising connection could lead to new avenues of research for brain enhancements, adds Chalasani.

How did researchers test all of this in worms exactly? They began by placing worms in dishes that contained either a large or a small patch of edible bacteria. Worms in the smaller patches tended to reach the edges more frequently, experiencing large changes in variability (edges have large amounts of food compared to the center). Worms on the large patch, however, reached the edge less frequently, thereby experiencing a general stable environment (mainly an area with constant food).

Using genetics, imaging, behavioral analysis and other techniques, researchers found that when worms are on small patches, the two pairs of high-threshold neurons respond to the greater variation and signal leading to increased dopamine. When worms in these smaller patches (and higher dopamine) were taken out and put into a new dish, they explored a larger area, taking more of a risk. Worms from the larger patches, however, produced less dopamine and were more cautious, exploring just a small space when placed in a new area.

Additionally, when the protein CREB was present in larger amounts, the team found that the worms took far less time to learn about their food variability. "Normally the worms took about 30 minutes or so to explore and learn about food, but as you keep increasing the CREB protein they learn it faster," says Chalasani. "So dopamine stores the memory of what these worms learn while CREB regulates how quickly they learn."

INFORMATION:

Authors include Adam J. Calhoun of the University of California, San Diego; Navin Pokala of The Rockefeller University; and Ada Tong, James A. J. Fitzpatrick, Tatyana O. Sharpee and Sreekanth H. Chalasani, all of the Salk Institute.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation and the Rita Allen Foundation.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probes fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, MD, the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.