Bacterial 'memory' targets invading viruses

Tel Aviv University researchers uncover mechanism that defends bacteria from an autoimmune attack

2015-04-16

(Press-News.org) One of the immune system's most critical challenges is to differentiate between itself and foreign invaders -- and the number of recognized autoimmune diseases, in which the body attacks itself, is on the rise. But humans are not the only organisms contending with "friendly fire."

Even single-celled bacteria attack their own DNA. What protects these bacteria, permitting them to survive the attacks?

A new study published in Nature by a team of researchers at Tel Aviv University and the Weizmann Institute of Science now reveals the precise mechanism that bacteria's defense systems use to target invading viruses, protecting their own infrastructures. According to the study, led by Prof. Udi Qimron of the Department of Clinical Microbiology and Immunology at TAU's Sackler Faculty of Medicine and Prof. Rotem Sorek of the Weizmann Institute's Molecular Genetics Department and conducted by TAU graduate student Moran Goren and Weizmann graduate student Asaf Levy, bacteria adopt two unique strategies to produce an appropriate, targeted response to foreign invaders -- at minimal damage to their own DNA.

Thanks for the memories?

"Bacteria defend themselves from viral attacks thorough a defense system called 'CRISPR-Cas,'" said Prof. Qimron. "This system is adaptive, meaning it can 'memorize' a virus by sampling pieces of its DNA, and consequently launch an attack against the virus in future encounters. It was a mystery how bacteria are able to avoid attacking themselves and preferentially target viruses. But, it was only logical that the avoidance would be developed during the early 'memorization' stage of this mechanism rather than in the latter stages of attack."

A virus kills a cell by harnessing a host cell's replication machinery to make copies of itself. Years ago, Prof. Qimron pioneered studies on the memorization mechanism of CRISPR-Cas, which protects the bacterial host by inserting a short sequence of invading viral DNA straight into the bacterial genome to "remember" the infection. Bits of the viral DNA stored in special sections of the genome were found to form immune memory. In subsequent infections, the CRISPR system used these genetic sequences to create short strands of RNA that exactly fit the genetic sequence of the virus. Once protein complexes attached to the RNA identified the viral DNA, they destroyed the invading virus.

"We knew there had to be a sophisticated mechanism in place. Otherwise the bacteria, which tend to destroy its more plentiful viral invaders, would succumb to attacks, which is usually not the case," said Prof. Qimron.

Making a monkey out of DNA

Qimron's and Sorek's groups teamed up to pinpoint the precise mechanism by recording and analyzing tens of millions of memorization events against foreign DNA by the CRISPR-Cas system. The researchers injected plasmids - short, circular pieces of DNA that mimic foreign DNA - into bacteria. Two proteins, Cas1 and Cas2, were found to be responsible for acquiring pieces of plasmid DNA and avoiding bacterial DNA. In other words, the CRISPR system successfully memorized the foreign DNA for future attack, while the self-bacterial DNA was only rarely memorized.

"We can possibly use this knowledge to protect a DNA piece from attack," said Prof. Qimron. "The CRISPR-Cas system has been used in many applications, including the manipulation of DNA to generate a genetically engineered monkey. It is considered one of the most promising tools of future medicine."

The researchers are currently studying the molecular details of the memorization mechanism.

INFORMATION:

American Friends of Tel Aviv University supports Israel's most influential, most comprehensive and most sought-after center of higher learning, Tel Aviv University (TAU). US News & World Report's Best Global Universities Rankings rate TAU as #148 in the world, and the Times Higher Education World University Rankings rank TAU Israel's top university. It is one of a handful of elite international universities rated as the best producers of successful startups, and TAU alumni rank #9 in the world for the amount of American venture capital they attract.

A leader in the pan-disciplinary approach to education, TAU is internationally recognized for the scope and groundbreaking nature of its research and scholarship -- attracting world-class faculty and consistently producing cutting-edge work with profound implications for the future.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2015-04-16

(PHILADELPHIA) - As cesarean section rates continue to climb in the United States, researchers are looking to understand the factors that might contribute. There has been debate in the field about whether non-medically required induction of labor leads to a greater likelihood of C-section, with some studies showing an association and others demonstrating that inductions at full term can actually protect both the mothers and babies. In order to tease apart the evidence, a new analysis pooled the results from five randomized controlled trials including 844 women, and found ...

2015-04-16

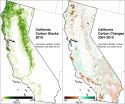

Berkeley - A new study quantifying the amount of carbon stored and released through California forests and wildlands finds that wildfires and deforestation are contributing more than expected to the state's greenhouse gas emissions.

The findings, published online today (Wednesday, April 15), in the journal Forest Ecology and Management, came from a collaborative project led by the National Park Service and the University of California, Berkeley. The results could have implications for California's efforts to meet goals mandated by the state Global Warming Solutions Act, ...

2015-04-16

Researchers at the Angiocardioneurology Department of the Neuromed Scientific Institute for Research, Hospitalisation and Health Care of Pozzilli (Italy), have found, in animal models, that the absence of a certain enzyme causes a syndrome resembling the Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). The study, published in the international journal EMBO Molecular Medicine, paves the way for a greater understanding of this childhood and adolescent disease, aiming at innovative therapeutic approaches.

Described for the first time in 1845, but came to the fore only in ...

2015-04-16

HEIDELBERG, 15 April 2015 - A genetic investigation of individuals in the Framingham Heart Study may prove useful to identify novel targets for the prevention or treatment of high blood pressure. The study, which takes a close look at networks of blood pressure-related genes, is published in the journal Molecular Systems Biology.

More than one billion people worldwide suffer from high blood pressure and this contributes significantly to deaths from cardiovascular disease. It is hoped that advances in understanding the genetic basis of how blood pressure is regulated ...

2015-04-16

Philadelphia, PA, April 16, 2015 - About 15% of patients with Lyme disease develop peripheral and central nervous system involvement, often accompanied by debilitating and painful symptoms. New research indicates that inflammation plays a causal role in the array of neurologic changes associated with Lyme disease, according to a study published in The American Journal of Pathology. The investigators at the Tulane National Primate Research Center and Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center also showed that the anti-inflammatory drug dexamethasone prevents many ...

2015-04-16

New York, NY--While a large number of women quit or reduce smoking upon pregnancy recognition, many resume smoking postpartum. Previous research has estimated that approximately 70% of women who quit smoking during pregnancy relapse within the first year after childbirth, and of those who relapse, 67% resume smoking by three months, and up to 90% by six months.

A new study out in the Nicotine & Tobacco Research indicates the only significant predictor in change in smoking behaviors for women who smoked during pregnancy was in those who breastfed their infant, finding ...

2015-04-16

Children who are taught about preventing sexual abuse at school are more likely than others to tell an adult if they had, or were actually experiencing sexual abuse. This is according to the results of a new Cochrane review published in the Cochrane Library today. However, the review's authors say that more research is needed to establish whether school-based programmes intended to prevent sexual abuse actually reduce the incidence of abuse.

It is estimated that, worldwide, at least 1 in 10 girls and 1 in 20 boys experience some form of sexual abuse in childhood. Those ...

2015-04-16

Older adults with complex medical needs are occupying an increasing number of beds in acute care hospitals, and these patients are commonly cared for by hospitalists with limited formal geriatrics training. These clinicians are also hindered by a lack of research that addresses the needs of the older adult population. A new paper published today in the Journal of Hospital Medicine outlines a research agenda to address these issues.

To help support hospitalists in providing acute inpatient geriatric care, the Society of Hospital Medicine has developed a research agenda ...

2015-04-16

CHICAGO --- Walking at an easy pace for about three hours every week may be just enough physical activity to help prostate cancer survivors reduce damaging side effects of their treatment, according to a new Northwestern Medicine study.

"Non-vigorous walking for three hours per week seems to improve the fatigue, depression and body weight issues that affect many men post-treatment," said Siobhan Phillips, lead author of the study. "If you walk even more briskly, for only 90 minutes a week, you could also see similar benefits in these areas."

Phillips is a kinesiologist ...

2015-04-16

Philadelphia, PA, April 16, 2015 - With the advent of targeted lymphoma therapies on the horizon, it becomes increasingly important to differentiate the two major subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), which is the most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma. These are germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) and activated B-cell-like (ABC), which differ in management and outcomes. A report in The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics describes use of the reverse transcriptase?multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (RT-MLPA) assay for differentiating DLBCL subtypes. RT-MLPA ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Bacterial 'memory' targets invading viruses

Tel Aviv University researchers uncover mechanism that defends bacteria from an autoimmune attack