New strategy for mapping regulatory networks associated with multi-gene diseases

2015-04-23

(Press-News.org) WORCESTER, MA - Scientists at the University of Massachusetts Medical School have applied a powerful tool in a new way to characterize genetic variants associated with human disease. The work, published today in Cell, will allow scientists to more easily and efficiently describe genomic variations underlying complex, multi-gene diseases.

"Up to this point, we've only been able to investigate one disease-causing mutation at a time," said principal investigator Marian Walhout, PhD, co-director of the Program in Systems Biology and professor of molecular medicine at UMMS. "We now have a robust platform that allows us to interrogate hundreds of mutations in a single experiment. This will help us develop a map of the interactions that make up the networks that control gene expression and determine how mutations in the genome give rise to a variety of human diseases."

An explosion in whole genome studies, often called genome-wide association studies or GWAS, was brought about by vast improvements in gene sequencing technology that has helped scientists locate thousands of genetic variations associated with hundreds of different diseases. Yet, as many as 90 percent these mutations are found in areas of the genome that don't code for proteins, according to Dr. Walhout.

Mutations in transcription factors or their DNA binding sites can contribute to disease by disrupting gene regulation. This leads to too much, or not enough, of a target protein. A wide variety of diseases including cancer, neurological disorders, blood disorders and metabolic diseases have been linked to aberrant gene regulation.

"Most of the disease-associated mutations these GWAS have identified don't actually change the protein itself, but are located in regulatory regions and could, therefore, change the levels of the protein," said Juan Fuxman Bass, PhD, post-doctoral fellow and lead author of the Cell study. "The challenge for us has always been to identify how and why these mutations give rise to disease."

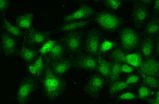

Using the enhanced, gene-centered yeast one-hybrid (eY1H) assays developed in 2011 by the Walhout group, the researchers were able to perform thousands of experiments involving 1,000 transcription factors and more than 100 genetic variants. As a result, they were able to detect both loss and gain of interactions between DNA sites and transcription factors that were consistent with changes in gene expression that were found in the associated diseases.

"This system provides a tool for the in-depth interrogation of the role that genetic variation and differences in transcription factor interactions play in disrupting the gene regulatory network," Walhout concluded. "It's a blueprint for understanding these networks and how this connectivity is affected in disease."

INFORMATION:

About the University of Massachusetts Medical School

The University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS), one of five campuses of the University system, comprises the School of Medicine, the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, the Graduate School of Nursing, a thriving research enterprise and an innovative public service initiative, Commonwealth Medicine. Its mission is to advance the health of the people of the commonwealth through pioneering education, research, public service and health care delivery with its clinical partner, UMass Memorial Health Care. In doing so, it has built a reputation as a world-class research institution and as a leader in primary care education. The Medical School attracts more than $240 million annually in research funding, placing it among the top 50 medical schools in the nation. In 2006, UMMS's Craig C. Mello, PhD, Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator and the Blais University Chair in Molecular Medicine, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, along with colleague Andrew Z. Fire, PhD, of Stanford University, for their discoveries related to RNA interference (RNAi). The 2013 opening of the Albert Sherman Center ushered in a new era of biomedical research and education on campus. Designed to maximize collaboration across fields, the Sherman Center is home to scientists pursuing novel research in emerging scientific fields with the goal of translating new discoveries into innovative therapies for human diseases.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2015-04-23

The oncologists Manuel Hidalgo, Director of the Clinical Research Programme of the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), and Ignacio Garrido-Laguna, member of the Experimental Therapeutics Program at Huntsman Cancer Institute of the University of Utah (USA), have recently published a review of state-of-the-art clinical treatments for pancreatic cancer -- including the most current therapies and innovative research -- in the prestigious scientific journal Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology.

In their study, which reviews around 200 scientific articles published ...

2015-04-23

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Using a technique that introduces tiny wrinkles into sheets of graphene, researchers from Brown University have developed new textured surfaces for culturing cells in the lab that better mimic the complex surroundings in which cells grow in the body.

"We know that cells are shaped by their surroundings," said Ian Y. Wong, assistant professor of engineering and one of the study's authors. "We've shown that you can make textured environments for cell culture fairly easily using graphene."

Traditionally, cell culture in the lab has ...

2015-04-23

An enzyme secreted by the body's fat tissue controls energy levels in the brain, according to new research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. The findings, in mice, underscore a role for the body's fat tissue in controlling the brain's response to food scarcity, and suggest there is an optimal amount of body fat for maximizing health and longevity.

The study appears April 23 in the journal Cell Metabolism.

"We showed that fat tissue controls brain function in a really interesting way," said senior author Shin-ichiro Imai, MD, PhD, professor of ...

2015-04-23

Dolphins that raise their voices to be heard in noisy environments expend extra energy in doing so, according to new research that for the first time measures the biological costs to marine mammals of trying to communicate over the sounds of ship traffic or other sources.

While dolphins expend only slightly more energy on louder whistles or other vocalizations, the metabolic cost may add up over time when the animals must compensate for chronic background noise, according to the research by scientists at NOAA Fisheries' Northwest Fisheries Science Center and the University ...

2015-04-23

TORONTO, ON. (23 April, 2015) - A new study led by University of Toronto researcher Dr. David Lam has discovered the trigger behind the most severe forms of cancer pain. Released in top journal Pain this month, the study points to TMPRSS2 as the culprit: a gene that is also responsible for some of the most aggressive forms of androgen-fuelled cancers.

Head of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the Faculty of Dentistry, Lam's research initially focused on cancers of the head and neck, which affect more than 550,000 people worldwide each year. Studies have shown that these ...

2015-04-23

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- A 47-year-old African-American woman has heavy menstrual bleeding and iron-deficiency anemia. She reports the frequent need to urinate during the night and throughout the day. A colonoscopy is negative and an ultrasonography shows a modestly enlarged uterus with three uterine fibroids, noncancerous growths of the uterus. She is not planning to become pregnant. What are her options?

Elizabeth (Ebbie) Stewart, M.D., chair of Reproductive Endocrinology at Mayo Clinic, says the woman has several options, but determining her best option is guided by her ...

2015-04-23

ANN ARBOR--Use of clean fuels and updated pollution control measures in the school buses 25 million children ride every day could result in 14 million fewer absences from school a year, based on a study by the University of Michigan and the University of Washington.

In research believed to be the first to measure the individual impact on children of the federal mandate to reduce diesel emissions, researchers found improved health and less absenteeism, especially among asthmatic children.

A change to ultra low sulfur diesel fuel reduced a marker for inflammation in ...

2015-04-23

Boosting teenagers' ability to cope with online risks, rather than trying to stop them from using the Internet, may be a more practical and effective strategy for keeping them safe, according to a team of researchers.

In a study, more resilient teens were less likely to suffer negative effects even if they were frequently online, said Haiyan Jia, post-doctoral scholar in information sciences and technology.

"Internet exposure does not necessarily lead to negative effects, which means it's okay to go online, but the key seems to be learning how to cope with the stress ...

2015-04-23

CAMBRIDGE, Mass--Drizzling honey on toast can produce mesmerizing, meandering patterns, as the syrupy fluid ripples and coils in a sticky, golden thread. Dribbling paint on canvas can produce similarly serpentine loops and waves.

The patterns created by such viscous fluids can be reproduced experimentally in a setup known as a "fluid mechanical sewing machine," in which an overhead nozzle deposits a thick fluid onto a moving conveyor belt. Researchers have carried out such experiments in an effort to identify the physical factors that influence the patterns that form. ...

2015-04-23

April 23, 2015 - Interventional treatments--especially surgery--provide good functional outcomes and a high cure rate for patients with lower-grade arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) of the brain, reports the May issue of Neurosurgery, official journal of the Congress of Neurological Surgeons. The journal is published by Wolters Kluwer.

The findings contrast with a recent trial reporting better outcomes without surgery or other interventions for AVMs. "On the basis of these data, in appropriately selected patients, we recommend treatment for low-grade brain AVMs," concludes ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] New strategy for mapping regulatory networks associated with multi-gene diseases