(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA -- A study tying the aging process to the deterioration of tightly packaged bundles of cellular DNA could lead to methods of preventing and treating age-related diseases such as cancer, diabetes and Alzheimer's disease, as detailed April 30, 2015, in Science.

In the study, scientists at the Salk Institute and the Chinese Academy of Science found that the genetic mutations underlying Werner syndrome, a disorder that leads to premature aging and death, resulted in the deterioration of bundles of DNA known as heterochromatin.

The discovery, made possible through a combination of cutting-edge stem cell and gene-editing technologies, could lead to ways of countering age-related physiological declines by preventing or reversing damage to heterochromatin.

"Our findings show that the gene mutation that causes Werner syndrome results in the disorganization of heterochromatin, and that this disruption of normal DNA packaging is a key driver of aging," says Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, a senior author on the paper. "This has implications beyond Werner syndrome, as it identifies a central mechanism of aging--heterochromatin disorganization--which has been shown to be reversible."

Werner syndrome is a genetic disorder that causes people to age more rapidly than normal. It affects around one in every 200,000 people in the United States. People with the disorder suffer age-related diseases early in life, including cataracts, type 2 diabetes, hardening of the arteries, osteoporosis and cancer, and most die in their late 40s or early 50s.

The disease is caused by a mutation to the Werner syndrome RecQ helicase-like gene, known as the WRN gene for short, which generates the WRN protein. Previous studies showed that the normal form of the protein is an enzyme that maintains the structure and integrity of a person's DNA. When the protein is mutated in Werner syndrome it disrupts the replication and repair of DNA and the expression of genes, which was thought to cause premature aging. However, it was unclear exactly how the mutated WRN protein disrupted these critical cellular processes.

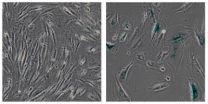

In their study, the Salk scientists sought to determine precisely how the mutated WRN protein causes so much cellular mayhem. To do this, they created a cellular model of Werner syndrome by using a cutting-edge gene-editing technology to delete WRN gene in human stem cells. This stem cell model of the disease gave the scientists the unprecedented ability to study rapidly aging cells in the laboratory. The resulting cells mimicked the genetic mutation seen in actual Werner syndrome patients, so the cells began to age more rapidly than normal. On closer examination, the scientists found that the deletion of the WRN gene also led to disruptions to the structure of heterochromatin, the tightly packed DNA found in a cell's nucleus.

This bundling of DNA acts as a switchboard for controlling genes' activity and directs a cell's complex molecular machinery. On the outside of the heterochromatin bundles are chemical markers, known as epigenetic tags, which control the structure of the heterochromatin. For instance, alterations to these chemical switches can change the architecture of the heterochromatin, causing genes to be expressed or silenced.

The Salk researchers discovered that deletion of the WRN gene leads to heterochromatin disorganization, pointing to an important role for the WRN protein in maintaining heterochromatin. And, indeed, in further experiments, they showed that the protein interacts directly with molecular structures known to stabilize heterochromatin--revealing a kind of smoking gun that, for the first time, directly links mutated WRN protein to heterochromatin destabilization.

"Our study connects the dots between Werner syndrome and heterochromatin disorganization, outlining a molecular mechanism by which a genetic mutation leads to a general disruption of cellular processes by disrupting epigenetic regulation," says Izpisua Belmonte. "More broadly, it suggests that accumulated alterations in the structure of heterochromatin may be a major underlying cause of cellular aging. This begs the question of whether we can reverse these alterations--like remodeling an old house or car--to prevent, or even reverse, age-related declines and diseases."

Izpisua Belmonte added that more extensive studies will be needed to fully understand the role of heterochromatin disorganization in aging, including how it interacts with other cellular processes implicated in aging, such as shortening of the end of chromosomes, known as telomeres. In addition, the Izpisua Belmonte team is developing epigenetic editing technologies to reverse epigenetic alterations with a role in human aging and disease.

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the paper include: Weiqi Zhang, Jingyi Li, Keiichiro Suzuki, Jing Qu, Ping Wang, Junzhi Zhou, Xiaomeng Liu, Ruotong Ren, Xiuling Xu, Alejandro Ocampo, Tingting Yuan, Jiping Yang, Ying Li, Liang Shi, Dee Guan, Huize Pan, Shunlei Duan, Zhichao Ding, Mo Li, Fei Yi, Ruijun Bai, Yayu Wang, Chang Chen, Fuquan Yang, Xiaoyu Li, Zimei Wang, Emi Aizawa, April Goebl, Rupa Devi Soligalla, Pradeep Reddy, Concepcion Rodriguez Esteban, Fuchou Tang and Guang-Hui Liu.

Funding for the study was provided by the Glenn Foundation, the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probes fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, MD, the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

HOUSTON - (April 30, 2015) - With the Millennium Development Goals established by the United Nations in 2000 coming to an end in 2015, and the new Sustainable Development Goals now in the works to establish a set of targets for the future of international development, experts at Baylor College of Medicine have developed a new tool to show why neglected tropical diseases, the most common infections of the world's poor, should be an essential component of these goals.

Using World Health Organization data for the number people at risk of parasitic worm infections in each ...

A detailed study of marine animals that died out over the past 23 million years can help identify which animals and ocean ecosystems may be most at risk of extinction today, according to an international team of paleontologists and ecologists.

In a paper to be published in the May 1 issue of the journal Science, researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, and other institutions report that worldwide patterns of extinction remained remarkably similar over this period, with the same groups of animals showing similar rates of extinction throughout and with a ...

Demand for seafood from wild fisheries and aquaculture around the world has nearly doubled over the past four decades. In the past several years, major retailers in developed countries have committed to source their seafood from only sustainably certified fisheries and aquaculture, even though it is not clear where that supply will come from.

A team of researchers led by the University of California, Davis, has focused its attention on fishery improvement projects, or FIPs, which are designed to bring seafood from wild fisheries to the certified market, with only a promise ...

HIV-1 continues to spread globally. While neither a cure, nor an effective vaccine are available, recent focus has been put on 'treatment-for-prevention', which is a method by which treatment is used to reduce the contagiousness of an infected person. A study published this week in PLOS Computational Biology challenges current treatment paradigms in the context of 'treatment for prevention' against HIV-1.

Sulav Duwal, Max von Kleist and their collaborators develop and employ optimal control theory to compute and assess diagnostic-guided vs. pro-active treatment strategies ...

Proteins inside a cell are in constant motion, changing shape continuously in order to carry out their functions. In addition, their multiple component atoms each have individual patterns of motion, making the entire protein a system of non-stop highly complex movement. Understanding how a protein moves is the key to developing drugs that can efficiently interact with it. But because of this complexity, protein motion has been notoriously difficult to study. Scientists at EPFL, IBS-Grenoble, and ENS-Lyon, have developed a new method for studying protein motion by first ...

The fossil record helps to predict which kinds of animals are more likely to go extinct. When combined with information about hotspots of human impacts and climate-change predictions, Smithsonian scientists and colleagues pinpoint animal groups and geographic areas of highest concern for marine conservation in the May 1 issue of Science magazine.

"Just as some groups of people are more prone to health problems like diabetes or heart disease, we can tell from the fossil record which groups of animals are naturally more likely to go extinct," said Aaron O'Dea, paleontologist ...

If you thought that a beetle with a machine gun built into its rear end was something that only exists in sci-fi movies, you should talk to Wendy Moore at the University of Arizona.

Many beetles secrete foul-smelling or bad-tasting chemicals from their abdomens to ward off predators, but bombardier beetles take it a step further. When threatened, they combine chemicals in an explosive chemical reaction chamber in their abdomen to simultaneously synthesize, heat and propel their defensive load as a boiling hot spray, complete with "gun smoke." They can even precisely ...

SEATTLE, Wash. -- More than 1000 dams have been removed across the United States because of safety concerns, sediment buildup, inefficiency or having otherwise outlived usefulness. A paper published today in Science finds that rivers are resilient and respond relatively quickly after a dam is removed.

"The apparent success of dam removal as a means of river restoration is reflected in the increasing number of dams coming down, more than 1,000 in the last 40 years," said lead author of the study Jim O'Connor, geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. "Rivers quickly erode ...

CAMBRIDGE, Mass--Bombardier beetles, which exist on every continent except Antarctica, have a pretty easy life. Virtually no other animals prey on them, because of one particularly effective defense mechanism: When disturbed or attacked, the beetles produce an internal chemical explosion in their abdomen and then expel a jet of boiling, irritating liquid toward their attackers.

Researchers had been baffled by the half-inch beetles' ability to produce this noxious spray while avoiding any physical damage. But now that conundrum has been solved, thanks to research by a ...

The vivid pigmentation of zebras, the massive jaws of sharks, the fight or flight instinct and the diverse beaks of Darwin's finches. These and other remarkable features of the world's vertebrates stem from a small group of powerful cells, called neural crest cells, but little is known about their origin.

Now Northwestern University scientists propose a new model for how neural crest cells, and thus vertebrates, arose more than 500 million years ago.

The researchers report that, unlike other early embryonic cells that have their potential progressively restricted as ...