(Press-News.org) Scooting around in the shallow, coastal waters of Puget Sound is one of the world's best suction cups.

It's called the Northern clingfish, and its small, finger-sized body uses suction forces to hold up to 150 times its own body weight. These fish actually hold on better to rough surfaces than to smooth ones, putting to shame industrial suction devices that give way with the slightest uneven surface.

Researchers at the University of Washington's Friday Harbor Laboratories on San Juan Island are studying this quirky little fish to understand how it can summon such massive suction power in wet, slimy environments. They are beginning to look at how the biomechanics of clingfish could be helpful in designing devices and instruments to be used in surgery and even to tag and track whales in the ocean.

"Northern clingfish's attachment abilities are very desirable for technical applications, and this fish can provide an excellent model for strongly and reversibly attaching to rough, fouled surfaces in wet environments," said Petra Ditsche, a postdoctoral researcher with Adam Summers' team at Friday Harbor Labs.

Ditsche presented her research on the sticky benefits of clingfish last month in Nashville at the Adhesive and Sealant Council's spring convention in a talk, "Bio-inspired suction attachment from the sea."

Clingfish have a disc on their bellies that is key to how they can hold on with such tenacity. The rim of the disc is covered with layers of micro-sized, hairlike structures. This layered effect allows the fish to stick to surfaces with different amounts of roughness.

"Moreover, the whole disc is elastic and that enables it to adapt to a certain degree on the coarser sites," Ditsche added.

Many marine animals can stick strongly to underwater surfaces - sea stars, mussels and anemones, to name a few - but few can release as fast as the clingfish, particularly after generating so much sticking power.

On land, lizards, beetles, spiders and ants also employ attachment forces to be able to move up walls and along the ceiling, despite the force of gravity. But unlike animals that live in the water, they don't have to deal with changing currents and other flow dynamics that make it harder to grab on and maintain a tight grip. (Read a recent paper by Ditsche and Summers on the differences between adhesion in water and on land.)

Clingfish's unique ability to hold with great force on wet, often slimy surfaces makes them particularly intriguing to study for biomedical applications. Imagine a bio-inspired device that could stick to organs or tissues without harming the patient.

"The ability to retract delicate tissues without clamping them is desirable in the field of laparoscopic surgery," Summers said. "A clingfish-based suction cup could lead to a new way to manipulate organs in the gut cavity without risking puncture."

Researchers are also interested in developing a tagging tool for whales that would allow a tag to noninvasively stick to the animal's body instead of puncturing the skin with a dart, which is often used for longer-term tagging.

Ditsche, Summers and the UW graduate and undergraduate students who are studying the Northern clingfish have no shortage of specimens to choose from. This species is found in the coastal waters near Mexico all the way up to Southern Alaska. They often cling to the rocks near the shore, and at low tide the researchers can poke around in tide pools and turn over rocks to collect the fish. If they can unstick them, that is.

There are about 110 known species in the clingfish family found all over the world. The population around the San Juan Islands is robust and healthy.

Now that they have measured the strength of the suction on different surfaces, the researchers plan to look next at how long clingfish can stick to a surface. They also want to understand why bigger clingfish can stick better than smaller ones, and what implications that could have on developing materials based on their properties.

INFORMATION:

This research is funded by the National Science Foundation and the Seaver Foundation.

For more information, contact Ditsche at pditsche@uw.edu or 360-610-0860.

A recent study reported in The Journal of Nuclear Medicine compared use of the novel Ga-68-PSMA-ligand PET/CT with other imaging methods and found that it had substantially higher detection rates of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) in patients with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Discovering a recurrence early can strongly influence further clinical management, so it is especially noteworthy that this hybrid PSMA-ligand identified a large number of positive findings in the clinically important range of low PSA-values ( END ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - As greater atmospheric carbon dioxide boosts sea temperatures, tropical corals face a bleak future. New climate model projections show that conditions are likely to increase the frequency and severity of coral disease outbreaks, reports a team of researchers led by Cornell University scientists, published today (May 4) in Nature Climate Change.

Download study, FAQ and photos: https://cornell.box.com/coral-disease

Conserving coral reefs is crucial to maintaining the biodiversity of our oceans and sustaining the livelihoods of the 500 million people that ...

A new study published in Marketing Science, a journal of the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS), shows double-digit revenue growth for firms that create their own brand-specific online communities.

The study, Social Dollars: The Economic Impact of Customer Participation in a Firm-Sponsored Online Customer Community, is by professors Puneet Manchanda of the University of Michigan, Grant Packard of Wilfrid Laurier University, and Adithya Pattabhiramaiah of the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Engaging consumers through online social ...

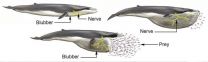

Nerves aren't known for being stretchy. In fact, "nerve stretch injury" is a common form of trauma in humans. But researchers reporting in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on May 4 have discovered that nerves in the mouths and tongues of rorqual whales can more than double their length with no trouble at all.

"These large nerves actually stretch and recoil like bungee cords," says A. Wayne Vogl of the University of British Columbia. "This is unlike other nerves in vertebrates, where the nerve is of a more fixed length that has enough slack in it to accommodate changes ...

University of British Columbia (UBC) researchers have discovered a unique nerve structure in the mouth and tongue of rorqual whales that can double in length and then recoil like a bungee cord.

The stretchy nerves explain how the massive whales are able to balloon an immense pocket between their body wall and overlying blubber to capture prey during feeding dives.

"This discovery was totally unexpected and unlike other nerve structures we've seen in vertebrates, which are of a more fixed length," says Wayne Vogl of UBC's Cellular and Physiological Sciences department.

"The ...

BOSTON, MA - The Emergency Department (ED) is at the convergence of the opioid epidemic as emergency physicians (EPs) routinely care for patients with adverse effects from opioids, including overdoses and those battling addiction, as well as treating patients that benefit from opioid use. Increasingly, EPs are required to distinguish between patients who are suffering from a condition that warrants opioids to relieve pain, and those who may be attempting to obtain these medications for other purposes, such as abuse or diversion. Overall, opioid pain reliever prescribing ...

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. -- May 4, 2015) Researchers led by St. Jude Children's Research Hospital scientists have identified a mechanism that helps leukemia cells resist glucocorticoids, a finding that lays the foundation for more effective treatment of cancer and possibly a host of autoimmune diseases. The findings appear online today in the scientific journal Nature Genetics.

The research focused on glucocorticoids, a class of steroid hormones. These hormones have been key ingredients in the chemotherapy cocktail that has helped to push long-term survival for the most common ...

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. - May 4, 2015) St. Jude Children's Research Hospital scientists have developed a significantly better computer tool for finding genetic alterations that play an important role in many cancers but were difficult to identify with whole-genome sequencing. The findings appear today in the scientific journal Nature Methods.

The tool is an algorithm called CONSERTING, short for Copy Number Segmentation by Regression Tree in Next Generation Sequencing.

St. Jude researchers created CONSERTING to improve identification of copy number alterations (CNAs) in the ...

COLUMBIA, Mo. -- Within the knee, two specialized, C-shaped pads of tissue called menisci perform many functions that are critical to knee-joint health. The menisci, best known as the shock absorbers in the knee, help disperse pressure, reduce friction and nourish the knee. Now, new research from the University of Missouri shows even small changes in the menisci can hinder their ability to perform critical knee functions. The research could provide new approaches to preventing and treating meniscal injuries as well as clues to understanding osteoarthritis; meniscal problems ...

(New York -- May 4, 2015) Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai researchers presented several landmark studies at the 2015 American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) meeting in Seattle.

AATS Highlights include:

First Successful 3D Printed Trachea

A team of researchers from Icahn School of Medicine have combined 3D printing technology with human stem cells to create the first successful 3D-printed biologic tracheal graft in an animal model. Using a biocompatible polymer, researchers created a customized 3D-printed tracheal graft seeded with stem cells. The ...