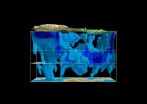

The scientists used seismic data from 227 East Asia earthquakes during 2007-2011, which they used to image depths to about 900 kilometers, or about 560 miles below ground.

Notable structures include a high velocity colossus beneath the Tibetan plateau, and a deep mantle upwelling beneath the Hangai Dome in Mongolia. The researchers say their line of work could potentially help find hidden hydrocarbon resources, and more broadly it could help explore the Earth under East Asia and the rest of the world.

"With the help of supercomputing, it becomes possible to render crystal-clear images of Earth's complex interior," principal investigator and lead author Min Chen said of the study. Chen is a postdoctoral research associate in the department of Earth Sciences at Rice University.

Chen and her colleagues ran simulations on the Stampede and Lonestar4 supercomputers of the Texas Advanced Computing Center through an allocation by XSEDE, the eXtreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment funded by the National Science Foundation.

"We are combining different kinds of seismic waves to render a more coherent image of the Earth," Chen said. "This process has been helped by supercomputing power that is provided by XSEDE."

"What is really new here is that this is an application of what is sometimes referred to as full waveform inversion in exploration geophysics," study co-author Jeroen Tromp said. Tromp is a professor of Geosciences and Applied and Computational Mathematics, and the Blair Professor of Geology at Princeton University.

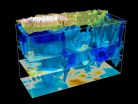

In essence the application combined seismic records from thousands of stations for each earthquake to produce scientifically accurate, high-res 3-D tomographic images of the subsurface beneath immense geological formations.

XSEDE provided more than just time on supercomputers for the science team. Through the Campus Champions program, researchers worked directly with Rice XSEDE champion Qiyou Jiang of Rice's Center for Research Computing and with former Rice staffer Roger Moye, who used Rice's DAVinCI supercomputer to help Chen with different issues she had with high performance computing." "They are the contacts I had with XSEDE," Chen said.

"These collaborations are really important," said Tromp of XSEDE. "They cannot be done without the help and advice of the computational science experts at these supercomputing centers. Without access to these computational resources, we would not be able to do this kind of work."

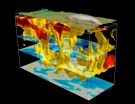

Like a thrown pebble generates ripples in a pond, earthquakes make waves that can travel thousands of miles through the Earth. A seismic wave slows down or speeds up a small percentage as it travels through changes in rock composition and temperature. The scientists mapped these wave speed changes to model the physical properties of rock hidden below ground.

Tromp explained that the goal for his team was to match the observed ground-shaking information at seismographic stations to fully numerical simulations run on supercomputers.

"In the computer, we set off these earthquakes," says Tromp. "The waves ripple across southeast Asia. We simulate what the ground motion should look like at these stations. Then we compare that to the actual observations.

The differences between our simulations and the observations are used to improve our models of the Earth's interior," Tromp said. "What's astonishing is how well those images correlate with what we know about the tectonics, in this case, of East Asia from surface observations."

The Tibetan Plateau, known as 'the roof of the world,' rises about three miles, or five kilometers above sea level. The details of how it formed remain hidden to scientists today.

The leading theory holds that the plateau formed and is maintained by the northward motion of the India plate, which forces the plateau to shorten horizontally and move upward simultaneously.

Scientists can't yet totally account for the speed of the movement of ground below the surface at the Tibetan Plateau or what happened to the Tethys Ocean that once separated the India and Eurasia plates. But a piece of the puzzle might have been found.

"We found that beneath the Tibetan plateau, the world's largest and highest plateau, there is a sub-vertical high velocity structure that extends down to the bottom of the mantle transition zone," Chen said.

The bottom of the transition zone goes to depths of 660 kilometers, she said. "Three-dimensional geometry of the high velocity structure depicts the lithosphere beneath the plateau, which gives clues of the fate of the subducted oceanic and the continental parts of the Indian plate under the Eurasian plate," Chen said.

The collision of plates at the Tibetan Plateau has caused devastating earthquakes, such as the recent 2015 Nepal earthquake at the southern edge of where the two plates meet. Scientists hope to use earthquakes to model the substructure and better understand the origins of these earthquakes.

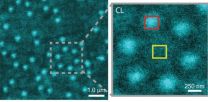

To reach any kind of understanding, the scientists first grappled with some big data, 1.7 million frequency-dependent traveltime measurements from seismic waveforms. "We applied this very sophisticated imaging technique called adjoint tomography with a key component that is a numerical code package called SPECFEM3D_GLOBE," Chen said.

Specifically, they used SPECFEM3D GLOBE, open source software maintained by the UC Davis Computational Infrastructure for Geodynamics. "It uses parallel computing to simulate the very complex seismic waves through the Earth," Chen said.

Even with the tools in place, the study was still costly. "The cost is in the simulations of the wave propagation," says Tromp. "That takes hundreds of cores for tens of minutes at a time per earthquake.

As you can imagine, that's a very expensive proposition just for one iteration simulating all these 227 earthquakes." In all, the study used about eight million CPU hours on the Stampede and Lonestar4 supercomputers.

"The big computing power of supercomputers really helped a lot in terms of shortening the simulation time and in getting an image of the Earth within a reasonable timeframe," said Chen. "It's still very challenging. It took us two years to develop this current model beneath East Asia. Hopefully, in the future it's going to be even faster."

Three-D imaging inside the Earth can help society find new resources, said Tromp. The iterative inversion methods they used to model structures deep below are the same ones used in exploration seismology to look for hidden hydrocarbons.

"There's a wonderful synergy at the moment," Tromp said. "The kinds of things we're doing here with earthquakes to try and image the Earth's crust and upper mantle and what people are doing in exploration geophysics to try and image hydrocarbon reservoirs."

"In my point of view, it's the era of big seismic data," Chen said. She said their ultimate goal is to make everything about seismic imaging methods automatic and accessible by anyone to better understand the Earth.

It sounded something like a Google Earth for inside the Earth itself. "Right, exactly. Assisted by the supercomputing systems of XSEDE, you can have a tour inside the Earth and possibly make some new discoveries." Chen said.

INFORMATION:

The science team for this study included Min Chen and Fenglin Niu of Rice University; Qinya Liu of the University of Toronto; Jeroen Tromp of Princeton University; and Xiufen Zheng of the Institute of Geophysics, China Earthquake Administration, Beijing, China. The National Science Foundation (US) provided the study funding.

The DAVinCI supercomputer is administered by Rice's Ken Kennedy Institute for Information Technology and supported by the National Science Foundation. The researchers also thank Kiran Thyagaraja, Franco Bladilo, and Kim Andrews for their assistance with work on DAVinCI.