INFORMATION:

Eastern diamondback rattlesnakes' quest for fire

Radio-tracking research shows eastern diamondbacks, a now-rare species for which endangered status was recently petitioned, have a crucial need for pine savanna, which requires periodic wildfires or managed burns to maintain the open-canopy forest

2015-05-21

(Press-News.org) Two words that arouse immediate fear in some people inspire something else altogether in Jennifer Fill.

"I love snakes and fire," Fill says. "When I was looking at grad schools, I thought, 'if I can just combine those two things, I bet I'll be really happy.'"

It's not about cozy campfires or garden-variety garters for Fill, a biologist who recently defended her dissertation at the University of South Carolina. The fires she's interested in are forest fires, and the snake that was the subject of her doctoral studies is Crotalus adamanteus, commonly called the eastern diamondback rattlesnake.

Once widespread throughout the southeastern U.S., eastern diamondback rattlesnakes have become extremely rare due to loss of their habitat. An eastern diamondback hasn't been spotted in the wild in Louisiana in twenty years, it's become a state-protected rarity in North Carolina, and conservationists applied in 2011 to have it listed federally as an endangered species.

One key element of the diamondback's natural habitat is Fill's second research love: fire. Diamondbacks have long been associated with open-canopy forests, or savannas, in the southeastern U.S. These habitats experience frequents fires, which turn out to be no problem for at least one important tree, the longleaf pine, Pinus palustris. Fill says its combination of growth patterns and structure make the longleaf pine one of the most fire-resistant trees around.

"For its first six to twelve years, it stays a little seedling at ground level," she says. "It develops a deep taproot, and if a fire comes through, the needles burn in a way that protects the growing tip of the plant."

After those early years of looking more like grass or a tiny bush at ground level, the longleaf pine has a burst of growth, a "bolting" stage that manifests a tall tree with a firm root. In the southeastern coastal plain, the tree creates a natural habitat of well-spaced pines with a dense groundcover of grass and low-lying shrubs -- fuel for the frequent and necessary fires in the savannas.

A savanna ecosystem supports the kinds of medium-sized mammals that eastern diamondbacks subsist on, such as rabbits, fox squirrels and raccoons. Fill recently published a paper in PLOS ONE showing just how critical that open-canopy environment is to the diamondback. Using telemetry to follow the weekly-to-daily movements of a group of snakes in Colleton County, on the southeastern coastal plain of South Carolina, she and her colleagues demonstrated that pine savanna was an integral part of the animal's natural habitat.

Conservation-minded scientists are interested in identifying surrogate habitats that might support the dwindling population of eastern diamondbacks. The recent paper addressed marshes as a potential candidate, but one particularly noteworthy observation in the research is that every eastern diamondback they studied had pine savanna as a part of its home range.

Open-canopy longleaf pine forests have been drastically reduced in acreage over the years for a number reasons, one of which can be ascribed to a common conservation practice promoted by another animal used as an emblem -- Smokey the Bear.

Forest fire prevention has had a side effect of converting many savannas into dense forests by removing the selection pressure of natural, periodic wildfires or managed fires from the equation, Fill says. The longleaf pine is out-competed by other tree species, the open canopy is closed and the ecosystem changes accordingly.

Many property owners, however, actively manage their land with prescribed burns. Quail habitats, for example, are best maintained with periodic fires, and acreage managed in that way (Fill worked on such a property for her recent paper) supports the diamondback populations as well.

Fill, who is interested in applying academic research to practical conservation efforts, appreciates the disposition of the rattlesnakes -- and snakes in general after working with them for years. She had to periodically capture diamondbacks to replace or fit a new radio transmitter for tracking, and handling them over the years reinforced the textbook conclusion that snakes are innately shy, even ones that might have a fearsome reputation.

"The very last thing that they want is for you to even see them, much less rattle or bite," she says. "Once I was tracking a snake and I knew she was really close by, and it took me forever to even see her, and she was right next to me. She didn't even rattle when I was picking her up with the hook and putting her in a bag.

"These snakes are not aggressive animals and actually have distinct personalities. It's been a privilege to see how they live in these fiery places."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Report on expanded success initiative points to changes in schools

2015-05-21

A new report on New York City's Expanded Success Initiative (ESI), which is designed to boost college and career readiness among Black and Latino male students, finds that the schools involved are changing the way they operate and offering students opportunities they would not otherwise have.

"There is strong evidence that these schools are doing something different as a result of ESI," says the study's lead author, Adriana Villavicencio, senior research associate at the Research Alliance for New York City Schools. "We are seeing important shifts in the tone and culture ...

Symbiosis turns messy in 13-year cicadas

2015-05-21

Bacteria that live in the guts of cicadas have split into many separate but interdependent species in a strange evolutionary phenomenon that leaves them reliant on a bloated genome, a new paper by CIFAR Fellow John McCutcheon's lab (University of Montana) has found.

Cicadas subsist on tree sap, which doesn't provide them all the nutrients they need to live. Bacteria in their gut, including one called Hodgkinia, turns the sap into amino acids that sustain them during their unusual lives. Cicadas spend most of their lives underground before emerging in droves, singing loudly, ...

Social structure 'helps birds avoid a collision course'

2015-05-21

The sight of skilful aerial manoeuvring by flocks of Greylag geese to avoid collisions with York's Millennium Bridge intrigued mathematical biologist Dr Jamie Wood. It raised the question of how birds collectively negotiate man-made obstacles such as wind turbines which lie in their flight paths.

It led to a research project with colleagues in the Departments of Biology and Mathematics at York and scientists at the Animal and Plant Health Agency. The study found that the social structure of groups of migratory birds may have a significant effect on their vulnerability ...

Turn that defect upside down

2015-05-21

Most people see defects as flaws. A few Michigan Technological University researchers, however, see them as opportunities. Twin boundaries -- which are small, symmetrical defects in materials -- may present an opportunity to improve lithium-ion batteries. The twin boundary defects act as energy highways and could help get better performance out of the batteries.

This finding, published in Nano Letters earlier this year, turns a previously held notion of material defects on its head. Reza Shahbazian-Yassar helped lead the study and holds a joint appointment at Michigan ...

Experts map surgical approaches for auditory brainstem implantation

2015-05-21

May 21, 2015 -- A technique called auditory brainstem implantation can restore hearing for patients who can't benefit from cochlear implants. A team of US and Japanese experts has mapped out the surgical anatomy and approaches for auditory brainstem implantation in the June issue of Operative Neurosurgery, published on behalf of the Congress of Neurological Surgeons by Wolters Kluwer.

Dr. Albert L. Rhoton, Jr., and colleagues of University of Florida, Gainesville, and Fukuoka University, Japan, performed a series of meticulous dissections to demonstrate and illustrate ...

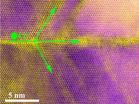

How supercooled water is prevented from turning into ice

2015-05-21

Water behaves in mysterious ways. Especially below zero, where it is dubbed supercooled water, before it turns into ice. Physicists have recently observed the spontaneous first steps of the ice formation process, as tiny crystal clusters as small as 15 molecules start to exhibit the recognisable structural pattern of crystalline ice. This is part of a new study, which shows that liquid water does not become completely unstable as it becomes supercooled, prior to turning into ice crystals. The team reached this conclusion by proving that an energy barrier for crystal formation ...

Infections can affect your IQ

2015-05-21

New research shows that infections can impair your cognitive ability measured on an IQ scale. The study is the largest of its kind to date, and it shows a clear correlation between infection levels and impaired cognition.

Anyone can suffer from an infection, for example in their stomach, urinary tract or skin. However, a new Danish study shows that a patient's distress does not necessarily end once the infection has been treated. In fact, ensuing infections can affect your cognitive ability measured by an IQ test:

"Our research shows a correlation between hospitalisation ...

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals in baby teethers

2015-05-21

This news release is available in German. FRANKFURT. In laboratory tests, two out of ten teethers, plastic toys used to sooth babies' teething ache, release endocrine disrupting chemicals. One product contains parabens, which are normally used as preservatives in cosmetics, while the second contains six so-far unidentified endocrine disruptors. The findings were reported by researchers at the Goethe University in the current issue of the Journal of Applied Toxicology.

"The good news is that most of the teethers we analyzed did not contain any endocrine disrupting ...

Simulations predict flat liquid

2015-05-21

Computer simulations have predicted a new phase of matter: atomically thin two-dimensional liquid.

This prediction pushes the boundaries of possible phases of materials further than ever before. Two-dimensional materials themselves were considered impossible until the discovery of graphene around ten years ago. However, they have been observed only in the solid phase, because the thermal atomic motion required for molten materials easily breaks the thin and fragile membrane. Therefore, the possible existence of an atomically thin flat liquid was considered impossible.

Now ...

How our gut changes across the life course

2015-05-21

Scientists and clinicians on the Norwich Research Park have carried out the first detailed study of how our intestinal tract changes as we age, and how this determines our overall health.

As well as digesting food, the gut plays a central role in programming our immune system, and provides an effective barrier to bacteria that could make us ill. In particular, immune cells that line the gut work to maintain the integrity of the barrier, as well as maintaining a balance that provides a healthy environment for beneficial bacteria, but reacts to combat invasion by pathogenic ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists design solar-responsive biochar that accelerates environmental cleanup

Construction of a localized immune niche via supramolecular hydrogel vaccine to elicit durable and enhanced immunity against infectious diseases

Deep learning-based discovery of tetrahydrocarbazoles as broad-spectrum antitumor agents and click-activated strategy for targeted cancer therapy

DHL-11, a novel prieurianin-type limonoid isolated from Munronia henryi, targeting IMPDH2 to inhibit triple-negative breast cancer

Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro inhibitors and RIPK1 inhibitors with synergistic antiviral efficacy in a mouse COVID-19 model

Neg-entropy is the true drug target for chronic diseases

Oxygen-boosted dual-section microneedle patch for enhanced drug penetration and improved photodynamic and anti-inflammatory therapy in psoriasis

Early TB treatment reduced deaths from sepsis among people with HIV

Palmitoylation of Tfr1 enhances platelet ferroptosis and liver injury in heat stroke

Structure-guided design of picomolar-level macrocyclic TRPC5 channel inhibitors with antidepressant activity

Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: An evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines

New global review reveals integrating finance, technology, and governance is key to equitable climate action

New study reveals cyanobacteria may help spread antibiotic resistance in estuarine ecosystems

Around the world, children’s cooperative behaviors and norms converge toward community-specific norms in middle childhood, Boston College researchers report

How cultural norms shape childhood development

University of Phoenix research finds AI-integrated coursework strengthens student learning and career skills

Next generation genetics technology developed to counter the rise of antibiotic resistance

Ochsner Health hospitals named Best-in-State 2026

A new window into hemodialysis: How optical sensors could make treatment safer

High-dose therapy had lasting benefits for infants with stroke before or soon after birth

‘Energy efficiency’ key to mountain birds adapting to changing environmental conditions

Scientists now know why ovarian cancer spreads so rapidly in the abdomen

USF Health launches nation’s first fully integrated institute for voice, hearing and swallowing care and research

Why rethinking wellness could help students and teachers thrive

Seabirds ingest large quantities of pollutants, some of which have been banned for decades

When Earth’s magnetic field took its time flipping

Americans prefer to screen for cervical cancer in-clinic vs. at home

Rice lab to help develop bioprinted kidneys as part of ARPA-H PRINT program award

Researchers discover ABCA1 protein’s role in releasing molecular brakes on solid tumor immunotherapy

Scientists debunk claim that trees in the Dolomites anticipated a solar eclipse

[Press-News.org] Eastern diamondback rattlesnakes' quest for fireRadio-tracking research shows eastern diamondbacks, a now-rare species for which endangered status was recently petitioned, have a crucial need for pine savanna, which requires periodic wildfires or managed burns to maintain the open-canopy forest