(Press-News.org) A 333-million year old broken bone is causing fossil scientists to reconsider the evolution of land-dwelling vertebrate animals, says a team of palaeontologists, including QUT evolutionary biologist Dr Matthew Phillips, and colleagues at Monash University and Queensland Museum.

Analysis of a fractured and partially healed radius (front-leg bone) from Ossinodus pueri, a large, primitive, four-legged (tetrapod), salamander-like animal, found in Queensland, pushes back the date for the origin of demonstrably terrestrial vertebrates by two million years, said Dr Phillips, a researcher in the Vertebrate Evolution Group in QUT's School of Earth, Environmental and Biological Sciences.

"Previously described partial skeletons of Ossinodus suggest this species could grow to more than 2m long and perhaps to around 50kg," Dr Phillips said.

"Its age raises the possibility that the first animals to emerge from the water to live on land were large tetrapods in Gondwana in the southern hemisphere, rather than smaller species in Europe.

"The evolution of land-dwelling tetrapods from fish is a pivotal phase in the history of vertebrates because it called for huge physical changes, such as weight bearing skeletons and dependence on air-breathing."

Dr Phillips said the nature of the break in the radius bone was studied using high-resolution finite element analysis by Peter Bishop for his honours research at QUT.

"The nature of the fracture suggests the bone broke under high-force impact.

"The break was most plausibly caused by a fall on land because such force would be difficult to achieve with the cushioning effect of water.

"Indeed, the fracture is somewhat reminiscent of people falling on an outstretched arm and the humerus crashing into and fracturing the radius."

Dr Phillips said the researchers also found two other features that confirmed the tetrapod had spent substantial time on land.

"Firstly, the internal bone structure was consistent with re-modelling during life in accordance with forces generated by walking on land," he said.

"We also found evidence of blood vessels that enter the bone at low angles, potentially reducing stress concentrations in bones supporting body weight on land.

"The three findings taken together suggest that Ossinodus spent a significant part of its life on land. This is augmented by its exceptional degree of ossification, which is also consistent with weight bearing away from the buoyancy of water.

"This specimen of Ossinodus is our oldest vertebrate relative shown biomechanically to have spent significant time on land. It is two million years older than the previous undoubtedly terrestrial specimens found in Scotland, which were less than 40cm long."

Dr Phillips said the findings highlighted the value of combining studies on palaeontology, biomechanics and pathology to understand how extinct organisms lived.

INFORMATION:

The study Oldest Pathology in a Tetrapod Bone Illuminates the Origin of Terrestrial Vertebrates was conducted by Peter J. Bishop, Christopher W. Walmsley, Matthew J. Phillips, Michelle R. Quayle, Catherine A. Boisvert, and Colin R. McHenry was published in Plos One:

http://www.plosone.org/article/Authors/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0125723.

Research by Catherine Klein, an undergraduate in Bristol's School of Earth Sciences, shows that fossils from the previously unstudied Woodleaze Quarry belong to a new species of the 'Gloucester lizard' Clevosaurus (named in 1939 after Clevum, the Latin name for Gloucester).

In the Late Triassic, the hills of the South West of the UK formed an archipelago that was inhabited by small dinosaurs and relatives of the Tuatara, a living fossil from New Zealand. The limestone quarries of the region have many caves or fissures containing sediments filled with the bones of abundant ...

New research has revealed that parasitic 'vampire' plants that attach onto and derive nutrients from another living plant may benefit the abundance and diversity of surrounding vegetation and animal life.

By altering the densities of the hemiparasite (a parasitic plant that also photosynthesises) Rhinanthus minor, in the Castle Hill National Nature Reserve in Sussex, ecologists from the Universities of York, Sussex and Lincoln were able to assess the impacts of the 'vampire' plants on the biodiversity of a species-rich semi-natural grassland. The scientists compared ...

NORTH GRAFTON, Mass. (June 4, 2015)--Birds, like people, can suffer from conditions where a blood transfusion is a necessary life-saving measure. But in many instances, unless an avian donor is readily available, accessing blood is impossible because of the challenges associated with storing the species' red blood cells.

New research published in the American Journal of Veterinary Research has found that a substance called dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) shows promise as a potential cryopreservant for freezing avian blood.

"Birds are susceptible to various causes of blood ...

In many animal species, the chromosomes differ between the sexes. The male has a Y chromosome. In some animals, however, for example birds, it is the other way round. In birds, the females have their own sex chromosome, the W chromosome. For the first, researchers in Uppsala have mapped the genetic structure and evolution of the W chromosome.

Every individual of a species has the same sorts of chromosomes, with one exception. In many species, the way the sexes differ is that males have their own sex chromosome, the Y chromosome. This contains genes which result in the ...

ARLINGTON, Texas -- Toys, appliances, and even a sofa and coffee table can impact the way or when a baby first crawls, walks or achieves other growth milestones, but a new UT Arlington study finds that many parents are unaware of the significant role household items play in their infant's motor skill development.

Priscila Caçola, an assistant professor of kinesiology in the UT Arlington College of Nursing and Health Innovation, co-developed a simple questionnaire for caregivers of infants aged 3 to 18 months that she says can aid in the evaluation of toys and other ...

From AGU's blogs: Flooding, erosion risks rise as Gulf of Mexico waves loom larger

Waves in the northern Gulf of Mexico are higher than they were 30 years ago, contributing to a greater risk of coastal erosion and flooding in Florida, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, according to a new study in Geophysical Research Letters.

From Eos.org: Building Sandbars in the Grand Canyon

Annual controlled floods from one of America's largest dams are rebuilding the sandbars of the iconic Colorado River, according to a new article by U.S. Geological Survey scientists in Eos. ...

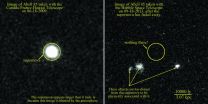

Sharp images obtained by the Hubble Space Telescope confirm that three supernovae discovered several years ago exploded in the dark emptiness of intergalactic space, having been flung from their home galaxies millions or billions of years earlier.

Most supernovae are found inside galaxies containing hundreds of billions of stars, one of which might explode per century per galaxy.

These lonely supernovae, however, were found between galaxies in three large clusters of several thousand galaxies each. The stars' nearest neighbors were probably 300 light years away, nearly ...

AURORA, Colo. June 3 -- As America's obesity epidemic continues to grow, a new study from the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus shows that a low-cost, non-profit weight loss program offers the kind of long-term results that often elude dieters.

'We know that people lose weight and then gain it back,' said study author Nia S. Mitchell, M.D., MPH, a researcher with the Division of General Internal Medicine at the Anschutz Health and Wellness Center at CU Anschutz. 'In this case, we found that people who renewed their annual membership in the program lost a ...

One of the most widely used tools in epigenetics research - the study of how DNA packaging affects gene expression - is chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), a technique that allows researchers to examine interactions between specific proteins and genomic regions. However, ChIP is a relative measurement, and has significant limitations that can lead to errors, poor reproducibility and an inability to be compared between experiments.

To address these issues, scientists from the University of Chicago have developed a new technique that calibrates ChIP experiments with an ...

About one-third of patients admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) will develop delirium, a condition that lengthens hospital stays and substantially increases one's risk of dying in the hospital, according to a new study led by Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers appearing in the British Medical Journal.

"Every patient who develops delirium will on average remain in the hospital at least one day longer," says one of the study's authors, Robert Stevens, M.D., a specialist in critical care and an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. ...