(Press-News.org) DURHAM, NC -- There aren't any giants or midgets when it comes to the cells in your body, and now Duke University scientists think they know why.

A new study appearing June 3 in Nature shows that a cell's initial size determines how much it will grow before it splits into two.

This finding goes against recent publications suggesting cells always add the same amount of mass, with some random fluctuations, before beginning division.

"It's like students going through college," said Lingchong You, the Paul Ruffin Scarborough Associate Professor of Engineering in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and the Center for Genomic and Computational Biology at Duke. "If they're not prepared, they take five or six years to graduate rather than taking more classes and overburdening themselves."

It all began with unexplainable oscillations. The team was looking at how genes on circular pieces of DNA called plasmids segregate when cells divide by tagging the genes with different fluorescent colors.

"We noticed oscillations in the expression of these colors in about 30 percent of the cells," You said. "And that's weird because we knew the genes involved aren't regulated, so this was incredibly baffling to us. We were very surprised."

The project was initiated by two former Duke graduate students, Yu Tanouchi and Anand Pai, now postdoctoral scientists at Stanford University and UC-San Francisco, respectively. The team was using a "mother machine," invented by Suckjoon Jun at UC-San Diego, to watch the division patterns of individual cells over many generations.

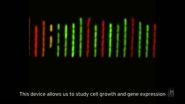

The device places individual cells -- in this case E. coli bacteria -- at the closed end of very small tubes. As each trapped cell grows and divides, its daughter cells are forced up the tube, where they are eventually swept away by a stream of nutrients.

The setup allows researchers to watch hundreds of cells go through divisions over dozens of generations and was key in seeing the baffling oscillations.

"Most studies take the average of many cells or many generations, which would make it impossible to see these oscillations," explained You. "That's why the single-cell analysis was critical, because these oscillations occur over many cell cycles with varying periods."

While trying to trace the origin of the genetic oscillations, You and his team were even more surprised to discover that the initial cell size also oscillated over multiple generations. After spending months trying to find the reason for the oscillations, Yu looked at correlations of different growth metrics like cell size at division, speed of growth and time to division.

And the results were a strikingly simple linear relationship, revealing that a cell's initial size determines how much biomass it would add before beginning cell division.

You and his colleagues then checked their findings against computer models. By using the same linear relationships and throwing in random fluctuations, they were able to recreate the oscillations in size in 30 to 40 percent of their virtual cell lines, just like in their experimental data.

Although the group does not know how the cells determine how long to grow based on their initial size, the computer models fit their experimental data precisely. But whether or not others in their field will be convinced is yet to be seen.

"During the review period of our paper, there were two experimental papers published in high-impact journals providing evidence for the 'adder model' (or the 'incremental model'), which is that when cells divide, they add a constant biomass on average," said You. "But the data are the data, and in our data we don't see this. The two models are very similar, but they have completely different implications for how cells maintain their uniform size. It will be interesting to see how people respond to our paper."

INFORMATION:

Also helping in the study were Heungwon Park, a postdoc in Nicolas Buchler's lab in the Department of Biology at Duke, and postdoc Shuqiang Huang and former graduate student Rumen Stamatov from the You lab.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health (R01GM098642, R01GM110494, DP2 OD008654-01), DuPont, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA-BAA-11-66) and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (BWF 1005769.01).

"A noisy linear map underlies oscillations in cell size and gene expression in bacteria." Yu Tanouchi, Anand Pai, Heungwon Park, Shuqiang Huang, Rumen Stamatov, Nicolas E. Buchler, Lingchong You. Nature, 2015. DOI: 10.1038/nature14562

The most aggressive largemouth bass in the lake are also the ones most prized by anglers. These are the fish that literally 'take the bait' and put the fun into both competitive and casual sport fishing.

Then, according to the rules of catch-and-release, the captive is unhooked and tossed back to swim away without any lasting consequences. But a new UConn study says there is an impact; the evolutionary path of a species may be on the line.

In a recent paper published in the journal PLOS ONE, a team of researchers led by Jan-Michael Hessenauer and Jason Vokoun of the ...

Armed with new knowledge about how neurodegenerative diseases alter brain structures, increasing numbers of neurologists, psychiatrists and other clinicians are adopting quantitative brain imaging as a tool to measure and help manage cognitive declines in patients. These imaging findings can help spur beneficial lifestyle changes in patients to reduce risk for Alzheimer's disease.

The concept that cognitive decline can be identified early and prevented by applying quantitative brain imaging techniques is the focus of "Hot Topics in Research: Preventive Neuroradiology ...

ATLANTA - June 4, 2015- Screening for colorectal cancer increased in lower socioeconomic status (SES) individuals after 2008, perhaps reflecting the Affordable Care Act's removal of financial barriers to screening according to a new analysis. The study, by American Cancer Society investigators, appears online in the journal Cancer.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) included a cost-sharing provision intended to reduce financial barriers for preventive services, including screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) and breast cancer (BC). To investigate whether ...

Withholding angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) for longer than two days after surgery is associated with a significantly increased risk of postoperative death, according to a study of more than 30,000 patients in the VA health care system by researchers at UC San Francisco and the San Francisco VA Medical Center (SFVAMC).

ARBs are prescribed for high blood pressure, heart disease and kidney disease, explained lead author Susan M. Lee, MD, an SFVAMC anesthesiologist and UCSF clinical instructor.

"For non-cardiac surgery, ARBs are commonly stopped on the day of surgery ...

Researchers at the University of Tokyo have succeeded in developing a new microscope capable of observing the magnetic sensitivity of photochemical reactions believed to be responsible for the ability of some animals to navigate in the Earth's magnetic field, on a scale small enough to follow these reactions taking place inside sub-cellular structures.

Several species of insects, fish, birds and mammals are believed to be able to detect magnetic fields - an ability known as magnetoreception. For example, birds are able to sense the Earth's magnetic field and use it to ...

The advent of online social networks has led to the rapid development of tools for understanding the interactions between members of the network, their activity, the connections, the hubs and nodes. But, any relationships between lots of entities, whether users of Facebook and Twitter, bees in a colony, birds in a flock, or the genes and proteins in our bodies can be analyzed with the same tools.

Now, research published in International Journal of Data Mining and Bioinformatics shows how social network analysis can be used to understand and identify the biomarkers in ...

SEATTLE - Physical activities, such as walking, as well as aerobics/calisthenics, biking, gardening, golfing, running, weight-lifting, and yoga/Pilates are associated with better sleep habits, compared to no activity, according to a new study from researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. In contrast, the study shows that other types of physical activity - such as household and childcare -- work are associated with increased cases of poor sleep habits. The full results of the study (Abstract #0246) will be presented during the poster ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - A new Cornell study of New York state apple orchards finds that pesticides harm wild bees, and fungicides labeled "safe for bees" also indirectly may threaten native pollinators.

The research, published June 3 in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, finds the negative effects of pesticides on wild bees lessens in proportion to the amount of natural areas near orchards.

Thirty-five percent of global food production benefits from insect pollinators, and U.S. farmers have relied exclusively on European honeybees, whose populations have been in decline for ...

CINCINNATI - Researchers have identified that parent-reported responses to a questionnaire called the Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis Symptom Score (PEESS® v2.0) correspond to clinical and biologic features of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) - a severe and often painful food allergy that renders children unable to eat a wide variety of foods.

This study, published online in Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, was led by researchers at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center.

Eosinophils are normal cellular components of the blood, but when the body ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Ask a plant researcher how the sex of a cucumber plant is determined and the person will tell you, "It's complicated." Depending on a complex mix of genetic and environmental factors, cucumbers can be seven different sexes. Some high-yield cucumber varieties produce only female flowers, and a new study identifies the gene duplication that causes this unusual trait.

The study, led by Zhangjun Fei of the Boyce Thompson Institute at Cornell University, and Sanwen Huang of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, in Beijing, appeared recently in The Plant ...