(Press-News.org) A team of researchers led by the University of Cambridge has described for the first time in humans how the epigenome - the suite of molecules attached to our DNA that switch our genes on and off - is comprehensively erased in early primordial germ cells prior to the generation of egg and sperm. However, the study, published today in the journal Cell, shows some regions of our DNA - including those associated with conditions such as obesity and schizophrenia - resist complete reprogramming.

Although our genetic information - the 'code of life' - is written in our DNA, our genes are turned on and off by epigenetic 'switches'. For example, small methyl molecules attach to our DNA in a process known as methylation and contribute to the regulation of gene activity, which is important for normal development. Methylation may also occur spontaneously or through our interaction with the environment - for example, periods of famine can lead to methylation of certain genes - and some methylation patterns can be potentially damaging to our health. Almost all of this epigenetic information is, however, erased in germ cells prior to transmission to the next generation

Professor Azim Surani from the Wellcome Trust/Cancer Research UK Gurdon Institute at the University of Cambridge, explains: "Epigenetic information is important for regulating our genes, but any abnormal methylation, if passed down from generation to generation, may accumulate and be detrimental to offspring. For this reason, the information needs to be reset in every generation before further information is added to regulate development of a newly fertilised egg. It's like erasing a computer disk before you add new data."

When an egg cell is fertilised by a sperm, it begins to divide into a cluster of cells known as a blastocyst, the early stage of the embryo. Within the blastocyst, some cells are reset to their master state, becoming stem cells, which have the potential to develop into any type of cell within the body. A small number of these cells become primordial germ cells with the potential to become sperm or egg cells.

In a study funded primarily by the Wellcome Trust, Professor Surani and colleagues showed that a process of reprogramming the epigenetic information contained in these primordial germ cells is initiated around two weeks into the embryo's development and continues through to around week nine. During this period, a genetic network acts to inhibit the enzymes that maintain or programme the epigenome until the DNA is almost clear of its methylation patterns.

Crucially, however, the researchers found that this process does not clear the entire epigenome: around 5% of our DNA appears resistant to reprogramming. These 'escapee' regions of the genome contain some genes that are particularly active in neuronal cells, which may serve important functions during development. However, data analysis of human diseases suggests that such genes are associated with conditions such as schizophrenia, metabolic disorders and obesity.

Walfred Tang, a PhD student who is the first author on the study, adds: "Our study has given us a good resource of potential candidates of regions of the genome where epigenetic information is passed down not just to the next generation but potentially to future generations, too. We know that some of these regions are the same in mice, too, which may provide us with the opportunity to study their function in greater detail."

Epigenetic reprogramming also has potential consequences for the so-called 'dark matter' within our genome. As much as half of human DNA is estimated to be comprised of 'retroelements', regions of DNA that have entered our genome from foreign invaders including bacteria and plant DNA. Some of these regions can be beneficial and even drive evolution - for example, some of the genes important to the development of the human placenta started life as invaders. However, others can have a potentially detrimental effect - particularly if they jump about within our DNA, potentially interfering with our genes. For this reason, our bodies employ methylation as a defence mechanism to suppress the activity of these retroelements.

"Methlyation is effective at controlling potentially harmful retroelements that might harm us, but if, as we've seen, methylation patterns are erased in our germ cells, we could potentially lose the first line of our defence," says Professor Surani.

In fact, the researchers found that a notable fraction of the retroelements in our genome are 'escapees' and retain their methylation patterns - particularly those retroelements that have entered our genome in our more recent evolutionary history. This suggests that our body's defence mechanism may be keeping some epigenetic information intact to protect us from potentially detrimental effects.

INFORMATION:

Our social connections and social compass define us to a large degree as human. Indeed, our tendency to act to benefit others without benefit to ourselves is regarded by some as the epitome of human nature and culture. But is it truly a quality unique to humans, or is this apparent virtue common to other species such as rats?

"We would not hesitate about helping an older person trying to cross the road", says Dr. Cristina Márquez, who conducted this study with Scott Rennie and Diana Costa from the Behavioural Neuroscience Lab, led by Dr. Marta Moita. "This type of ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- The process that allows our brains to learn and generate new memories also leads to degeneration as we age, according to a new study by researchers at MIT.

The finding, reported in a paper published today in the journal Cell, could ultimately help researchers develop new approaches to preventing cognitive decline in disorders such as Alzheimer's disease.

Each time we learn something new, our brain cells break their DNA, creating damage that the neurons must immediately repair, according to Li-Huei Tsai, the Picower Professor of Neuroscience and director ...

SEATTLE - Eating less late at night may help curb the concentration and alertness deficits that accompany sleep deprivation, according to results of a new study from researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania that will be presented at SLEEP 2015, the 29th annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies LLC.

"Adults consume approximately 500 additional calories during late-night hours when they are sleep restricted," said the study's senior author David F. Dinges, PhD, director of the Unit for Experimental Psychiatry ...

Medicare costs for older patients with oral cavity and pharyngeal cancers increased based on demographics, co-existing illnesses and treatment selection, according to a report published online by JAMA Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery.

Many cases of oral cavity cancer and most cases of pharyngeal cancer are diagnosed at advanced stages when management of the disease is complex and treatment is aggressive and involves multiple specialists. The publicly funded Medicare program provides an opportunity for researchers to estimate the cost of care for older patients with ...

Placenta doesn't prevent postpartum depression, ease pain, boost energy or aid lactation

Celebrities spike trend, but no studies show human benefits

Unknown risks to women and babies

CHICAGO -- Celebrities such as Kourtney Kardashian blogged and raved about the benefits of their personal placenta 'vitamins' and spiked women's interest in the practice of consuming their placentas after childbirth.

But a new Northwestern Medicine review of 10 current published research studies on placentophagy did not turn up any human or animal data to support the common ...

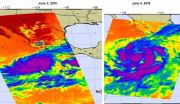

One of the instruments that flies aboard NASA's Aqua satellite looks at tropical cyclones using infrared light. In a comparison of infrared data from June 3 and 4, images show that Hurricane Blanca had weakened and became less organized.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument that flies aboard NASA's Aqua satellite measured cloud top temperatures in Blanca on June 3 at 20:17 UTC (4:23 p.m. EDT) when maximum sustained winds were near 140 mph (220 kph) with higher gusts. At the time, Blanca was a category 4 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. ...

DURHAM, NC -- There aren't any giants or midgets when it comes to the cells in your body, and now Duke University scientists think they know why.

A new study appearing June 3 in Nature shows that a cell's initial size determines how much it will grow before it splits into two.

This finding goes against recent publications suggesting cells always add the same amount of mass, with some random fluctuations, before beginning division.

"It's like students going through college," said Lingchong You, the Paul Ruffin Scarborough Associate Professor of Engineering in the ...

The most aggressive largemouth bass in the lake are also the ones most prized by anglers. These are the fish that literally 'take the bait' and put the fun into both competitive and casual sport fishing.

Then, according to the rules of catch-and-release, the captive is unhooked and tossed back to swim away without any lasting consequences. But a new UConn study says there is an impact; the evolutionary path of a species may be on the line.

In a recent paper published in the journal PLOS ONE, a team of researchers led by Jan-Michael Hessenauer and Jason Vokoun of the ...

Armed with new knowledge about how neurodegenerative diseases alter brain structures, increasing numbers of neurologists, psychiatrists and other clinicians are adopting quantitative brain imaging as a tool to measure and help manage cognitive declines in patients. These imaging findings can help spur beneficial lifestyle changes in patients to reduce risk for Alzheimer's disease.

The concept that cognitive decline can be identified early and prevented by applying quantitative brain imaging techniques is the focus of "Hot Topics in Research: Preventive Neuroradiology ...

ATLANTA - June 4, 2015- Screening for colorectal cancer increased in lower socioeconomic status (SES) individuals after 2008, perhaps reflecting the Affordable Care Act's removal of financial barriers to screening according to a new analysis. The study, by American Cancer Society investigators, appears online in the journal Cancer.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) included a cost-sharing provision intended to reduce financial barriers for preventive services, including screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) and breast cancer (BC). To investigate whether ...