(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, MA -- The process that allows our brains to learn and generate new memories also leads to degeneration as we age, according to a new study by researchers at MIT.

The finding, reported in a paper published today in the journal Cell, could ultimately help researchers develop new approaches to preventing cognitive decline in disorders such as Alzheimer's disease.

Each time we learn something new, our brain cells break their DNA, creating damage that the neurons must immediately repair, according to Li-Huei Tsai, the Picower Professor of Neuroscience and director of the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT.

This process is essential to learning and memory. "Cells physiologically break their DNA to allow certain important genes to be expressed," Tsai says. "In the case of neurons, they need to break their DNA to enable the expression of early response genes, which ultimately pave the way for the transcriptional program that supports learning and memory, and many other behaviors."

Slower DNA repair

However, as we age, our cells' ability to repair this DNA damage weakens, leading to degeneration, Tsai says. "When we are young, our brains create DNA breaks as we learn new things, but our cells are absolutely on top of this and can quickly repair the damage to maintain the functionality of the system," Tsai says. "But during aging, and particularly with some genetic conditions, the efficiency of the DNA repair system is compromised, leading to the accumulation of damage, and in our view this could be very detrimental."

In previous research into Alzheimer's disease in mice, the researchers found that even in the presymptomatic phase of the disorder, neurons in the hippocampal region of the brain contain a large number of DNA lesions, known as double strand breaks.

To determine how and why these double strand breaks are generated, and what genes are affected by them, the researchers began to investigate what would happen if they created such damage in neurons. They applied a toxic agent to the neurons known to induce double strand breaks, and then harvested the RNA from the cells for sequencing.

They discovered that of the 700 genes that showed changes as a result of this damage, the vast majority had reduced expression levels, as expected. Surprisingly though, 12 genes -- known to be those that respond rapidly to neuronal stimulation, such as a new sensory experience -- showed increased expression levels following the double strand breaks.

To determine whether these breaks occur naturally during neuronal stimulation, the researchers then treated the neurons with a substance that causes synapses to strengthen in a similar way to exposure to a new experience.

"Sure enough, we found that the treatment very rapidly increased the expression of those early response genes, but it also caused DNA double strand breaks," Tsai says.

The good with the bad

In further studies the researchers were able to confirm that an enzyme known as topoisomerase IIβ is responsible for the DNA breaks in response to stimulation, according to the paper's lead author Ram Madabhushi, a postdoc in Tsai's laboratory.

"When we knocked down this enzyme, we found that both double strand break formation and the expression of early response genes was reduced," Madabhushi says.

Finally, the researchers attempted to determine why the genes need such a drastic mechanism to allow them to be expressed. Using computational analysis, they studied the DNA sequences near these genes and discovered that they were enriched with a motif, or sequence pattern, for binding to a protein called CTCF. This "architectural" protein is known to create loops or bends in DNA.

In the early-response genes, the bends created by this protein act as a barrier that prevents different elements of DNA from interacting with each other -- a crucial step in the genes' expression.

The double strand breaks created by the cells allow them to collapse this barrier, and enable the early response genes to be expressed, Tsai says.

"Surprisingly then, even though conventional wisdom dictates that DNA lesions are very bad -- as this 'damage' can be mutagenic and sometimes lead to cancer -- it turns out that these breaks are part of the physiological function of the cell," Tsai says.

Previous research has shown that the expression of genes involved in learning and memory is reduced as people age. So the researchers now plan to carry out further studies to determine how the DNA repair system is altered with age, and how this compromises the ability of cells to cope with the continued production and repair of double strand breaks.

They also plan to investigate whether certain chemicals could enhance this DNA repair capacity.

INFORMATION:

SEATTLE - Eating less late at night may help curb the concentration and alertness deficits that accompany sleep deprivation, according to results of a new study from researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania that will be presented at SLEEP 2015, the 29th annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies LLC.

"Adults consume approximately 500 additional calories during late-night hours when they are sleep restricted," said the study's senior author David F. Dinges, PhD, director of the Unit for Experimental Psychiatry ...

Medicare costs for older patients with oral cavity and pharyngeal cancers increased based on demographics, co-existing illnesses and treatment selection, according to a report published online by JAMA Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery.

Many cases of oral cavity cancer and most cases of pharyngeal cancer are diagnosed at advanced stages when management of the disease is complex and treatment is aggressive and involves multiple specialists. The publicly funded Medicare program provides an opportunity for researchers to estimate the cost of care for older patients with ...

Placenta doesn't prevent postpartum depression, ease pain, boost energy or aid lactation

Celebrities spike trend, but no studies show human benefits

Unknown risks to women and babies

CHICAGO -- Celebrities such as Kourtney Kardashian blogged and raved about the benefits of their personal placenta 'vitamins' and spiked women's interest in the practice of consuming their placentas after childbirth.

But a new Northwestern Medicine review of 10 current published research studies on placentophagy did not turn up any human or animal data to support the common ...

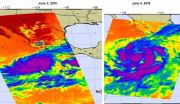

One of the instruments that flies aboard NASA's Aqua satellite looks at tropical cyclones using infrared light. In a comparison of infrared data from June 3 and 4, images show that Hurricane Blanca had weakened and became less organized.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument that flies aboard NASA's Aqua satellite measured cloud top temperatures in Blanca on June 3 at 20:17 UTC (4:23 p.m. EDT) when maximum sustained winds were near 140 mph (220 kph) with higher gusts. At the time, Blanca was a category 4 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. ...

DURHAM, NC -- There aren't any giants or midgets when it comes to the cells in your body, and now Duke University scientists think they know why.

A new study appearing June 3 in Nature shows that a cell's initial size determines how much it will grow before it splits into two.

This finding goes against recent publications suggesting cells always add the same amount of mass, with some random fluctuations, before beginning division.

"It's like students going through college," said Lingchong You, the Paul Ruffin Scarborough Associate Professor of Engineering in the ...

The most aggressive largemouth bass in the lake are also the ones most prized by anglers. These are the fish that literally 'take the bait' and put the fun into both competitive and casual sport fishing.

Then, according to the rules of catch-and-release, the captive is unhooked and tossed back to swim away without any lasting consequences. But a new UConn study says there is an impact; the evolutionary path of a species may be on the line.

In a recent paper published in the journal PLOS ONE, a team of researchers led by Jan-Michael Hessenauer and Jason Vokoun of the ...

Armed with new knowledge about how neurodegenerative diseases alter brain structures, increasing numbers of neurologists, psychiatrists and other clinicians are adopting quantitative brain imaging as a tool to measure and help manage cognitive declines in patients. These imaging findings can help spur beneficial lifestyle changes in patients to reduce risk for Alzheimer's disease.

The concept that cognitive decline can be identified early and prevented by applying quantitative brain imaging techniques is the focus of "Hot Topics in Research: Preventive Neuroradiology ...

ATLANTA - June 4, 2015- Screening for colorectal cancer increased in lower socioeconomic status (SES) individuals after 2008, perhaps reflecting the Affordable Care Act's removal of financial barriers to screening according to a new analysis. The study, by American Cancer Society investigators, appears online in the journal Cancer.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) included a cost-sharing provision intended to reduce financial barriers for preventive services, including screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) and breast cancer (BC). To investigate whether ...

Withholding angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) for longer than two days after surgery is associated with a significantly increased risk of postoperative death, according to a study of more than 30,000 patients in the VA health care system by researchers at UC San Francisco and the San Francisco VA Medical Center (SFVAMC).

ARBs are prescribed for high blood pressure, heart disease and kidney disease, explained lead author Susan M. Lee, MD, an SFVAMC anesthesiologist and UCSF clinical instructor.

"For non-cardiac surgery, ARBs are commonly stopped on the day of surgery ...

Researchers at the University of Tokyo have succeeded in developing a new microscope capable of observing the magnetic sensitivity of photochemical reactions believed to be responsible for the ability of some animals to navigate in the Earth's magnetic field, on a scale small enough to follow these reactions taking place inside sub-cellular structures.

Several species of insects, fish, birds and mammals are believed to be able to detect magnetic fields - an ability known as magnetoreception. For example, birds are able to sense the Earth's magnetic field and use it to ...