(Press-News.org) From a single drop of blood, researchers can now simultaneously test for more than 1,000 different strains of viruses that currently or have previously infected a person. Using a new method known as VirScan, researchers from Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) and Harvard Medical School tested for evidence of past viral infections, detecting on average 10 viral species per person. The new work sheds light on the interplay between a person's immunity and the human virome -- the vast array of viruses that can infect humans - with implications both for the clinic and for the field of immunology. The team reports its findings in Science on June 5.

"VirScan is a little like looking back in time: using this method, we can take a tiny drop of blood and determine what viruses a person has been infected with over the course of many years," said corresponding author Stephen Elledge, PhD, a principal investigator in the Division of Genetics at BWH and Gregor Mendel Professor of Genetics and of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. "What makes this so unique is the scale: right now, a physician needs to guess what virus might be at play and individually test for it. With VirScan, we can look for virtually all viruses, even rare ones, with a single test."

Classic blood tests, known as ELISA assays, can only detect one pathogen at a time. Additionally, ELISA assays have not been developed against all viruses, further limiting their usefulness. The team found the sensitivity and specificity of VirScan to be very similar to that of ELISA assays. The tests cost a comparable amount to run.

In the new study, Elledge and his colleagues tested blood samples from almost 600 people from Peru, the United States, South Africa and Thailand. The team developed and used a library of peptides - short protein fragments derived from viruses - representing more than 1,000 viral strains to find evidence of previous viral exposure. Rates of viral exposure varied by age, geographic location and HIV status, but the team found that a small number of peptides were recognized by the vast majority of people's immune systems. This pattern, suggesting that the immune systems of many individuals are hitting upon the same protein portion in a virus, could have important implications for understanding immunity.

VirScan may also help researchers find correlations between previous exposure to a particular virus and the development of a disease later in life. A connection between Epstein-Barr virus - one of the most common viruses seen in this study - and the risk of certain kinds of cancer is already known. The new method may help reveal other as-yet-unknown connections.

"A viral infection can leave behind an indelible footprint on the immune system," said Elledge. "Having a simple, reproducible method like VirScan may help us generate new hypotheses and understand the interplay between the virome and the host's immune system, with implications for a variety of diseases."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 DE018925-04, R37AI067073, DA033541, AI082630, N01-AI-30024, N01-AI-30024 and N01-AI-15422), the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (UKZNRSA1001), African Research Chairs Initiative, the Victor Daitz Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the HIVACAT program, CUTHIVAC 241904, TRF Senior Research Scholar, the Thailand Research Fund; the Chulalongkorn University Research Professor Program, Thailand; and the National Science Foundation.

Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) is a 793-bed nonprofit teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School and a founding member of Partners HealthCare. BWH has more than 3.5 million annual patient visits, is the largest birthing center in Massachusetts and employs nearly 15,000 people. The Brigham's medical preeminence dates back to 1832, and today that rich history in clinical care is coupled with its national leadership in patient care, quality improvement and patient safety initiatives, and its dedication to research, innovation, community engagement and educating and training the next generation of health care professionals. Through investigation and discovery conducted at its Brigham Research Institute (BRI), BWH is an international leader in basic, clinical and translational research on human diseases, more than 1,000 physician-investigators and renowned biomedical scientists and faculty supported by nearly $650 million in funding. For the last 25 years, BWH ranked second in research funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) among independent hospitals. BWH continually pushes the boundaries of medicine, including building on its legacy in transplantation by performing a partial face transplant in 2009 and the nation's first full face transplant in 2011. BWH is also home to major landmark epidemiologic population studies, including the Nurses' and Physicians' Health Studies and the Women's Health Initiative as well as the TIMI Study Group, one of the premier cardiovascular clinical trials group. For more information, resources and to follow us on social media, please visit BWH's online newsroom.

Harvard Medical School has more than 7,500 full-time faculty working in 11 academic departments located at the School's Boston campus or in one of 47 hospital-based clinical departments at 16 Harvard-affiliated teaching hospitals and research institutes. Those affiliates include Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston Children's Hospital, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Cambridge Health Alliance, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Hebrew Senior Life, Joslin Diabetes Center, Judge Baker Children's Center, Mass. Eye and Ear, Massachusetts General Hospital, McLean Hospital, Mount Auburn Hospital, Schepens Eye Research Institute, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital and VA Boston Healthcare System.

PHILADELPHIA - Around-the-clock rhythms guide nearly all physiological processes in animals and plants. Each cell in the body contains special proteins that act on one another in interlocking feedback loops to generate near-24 hour oscillations called circadian rhythms. These dictate behaviors controlled by the brain, such as sleeping and eating, as well as metabolic, hormonal, and other rhythms that are intrinsic to the organs of the body. For example, when you eat may have affects on rhythms controlling fat or sugar metabolism, illustrating how circadian and metabolic ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

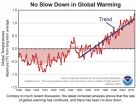

An analysis using updated global surface temperature data disputes the existence of a 21st century global warming slowdown described in studies including the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment. The new analysis suggests no discernable decrease in the rate of warming between the second half of the 20th century, a period marked by manmade warming, and the first fifteen years of the 21st century, a period dubbed a global warming "hiatus." Numerous studies have been done to explain the possible ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

Many species are migrating toward Earth's poles in response to climate change, and their habitats are shrinking in the process, researchers say. Two new reports focusing on marine organisms, which have been moving pole-ward at higher rates than terrestrial creatures, show how factors, including those not directly related to climate change, are limiting the ranges of corals and fish. Paul Muir and colleagues investigated 104 species of reef corals -- collectively known as the staghorn corals -- and confirmed the hypothesis ...

This news release is available in Japanese. With less than a drop of blood, a new technology called VirScan can identify all of the viruses that individuals have been exposed to over the course of their lives. Researchers used the screening technique with 569 people from around the world and found that, on average, their participants had been exposed to about 10 viral species over their lifetimes. VirScan provides a powerful and inexpensive tool for studying interactions between the human virome -- the collection of viruses known to infect humans, some of which don't ...

This news release is available in Japanese. Some of the world's last isolated tribes are emerging from the Amazon rainforest, forcing scientists and policymakers in South America to reconsider their policies regarding contact with such people. In this special package of news, Science correspondents Andrew Lawler and Heather Pringle report from Peru and Brazil, respectively -- two countries that are dealing with a spate of first encounters. Lawler describes contact between isolated tribespeople emerging from the forest and indigenous Peruvian villagers, who themselves ...

New technology developed by Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) researchers makes it possible to test for current and past infections with any known human virus by analyzing a single drop of a person's blood. The method, called VirScan, is an efficient alternative to existing diagnostics that test for specific viruses one at a time.

With VirScan, scientists can run a single test to determine which viruses have infected an individual, rather than limiting their analysis to particular viruses. That unbiased approach could uncover unexpected factors affecting individual ...

Friction is all around us, working against the motion of tires on pavement, the scrawl of a pen across paper, and even the flow of proteins through the bloodstream. Whenever two surfaces come in contact, there is friction, except in very special cases where friction essentially vanishes -- a phenomenon, known as "superlubricity," in which surfaces simply slide over each other without resistance.

Now physicists at MIT have developed an experimental technique to simulate friction at the nanoscale. Using their technique, the researchers are able to directly observe individual ...

A revolutionary power shift from internet giants such as Google to ordinary consumers is critically overdue, according to new research from a University of East Anglia (UEA) online privacy expert.

In a manifesto that ranges from "the right to be treated fairly on the internet" to finding a better, more nuanced approach to using the internet as an archive, Dr Paul Bernal of UEA's School of Law delves deeper into his research on the so-called 'right to be forgotten.' His paper, called 'A right to be remembered? Or the internet, warts and all,' will be presented today at ...

The red, itchy rash caused by varicella-zoster - the virus that causes chickenpox - usually disappears within a week or two. But once infection occurs, the varicella-zoster virus, or VZV, remains dormant in the nervous system, awaiting a signal that causes this "sleeper" virus to be re-activated in the form of an extremely unpleasant but common disease: herpes zoster, or shingles.

In a study recently published in PLOS Pathogens, scientists at Bar-Ilan University report on a novel experimental model that, for the first time, successfully mimics the "sleeping" and "waking" ...

Washington, DC-Unreliable estrogen measurements have had a negative impact on the treatment of and research into many hormone-related cancers and chronic conditions. To improve patient care, a panel of medical experts has called for accurate, standardized estrogen testing methods in a statement published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM).

The panel's recommendations are the first to address how improved testing methods can affect clinical care, and were developed based on discussions at an estrogen measurement workshop hosted ...