(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA - Around-the-clock rhythms guide nearly all physiological processes in animals and plants. Each cell in the body contains special proteins that act on one another in interlocking feedback loops to generate near-24 hour oscillations called circadian rhythms. These dictate behaviors controlled by the brain, such as sleeping and eating, as well as metabolic, hormonal, and other rhythms that are intrinsic to the organs of the body. For example, when you eat may have affects on rhythms controlling fat or sugar metabolism, illustrating how circadian and metabolic physiology are intricately intertwined.

Rev-erbα is a transcription factor (TF) that regulates a cell's internal clock and metabolic genes and has been the focus of the lab of Mitchell Lazar, MD, PhD, director of the Institute for Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, for more than two decades. Now, in a new study published online ahead of print in Science Express, the Lazar team describes how Rev-erbα regulates the clock in most cells in the body and metabolic genes in the liver, the body's key organ for metabolism of fat as well as sugar. "The exciting new finding is that, rather than use the same mechanism for regulating both the liver's clock and metabolic function, Rev-erb? does these jobs in distinct ways," Lazar explains.

Knowing the exact molecular players and the differences in these two important and related roles for Rev-erbα is helping scientists better understand and develop drugs for such disorders as diabetes, metabolic disorders in shift workers, and potentially even others.

"We showed that Rev-erbα modulates the clock and metabolism using different mechanisms of interacting with a cell's genome," notes Lazar of Rev-erbα's double duty. "On one hand, clock control requires Rev-erbα to bind directly to the genome, where it competes with other transcription factors, for repression of clock genes during the day."

On the other, Rev-erbα regulates metabolic genes in the liver at places in the genome where it is instructed to bind by other liver-specific factors. This indirect type of control by Rev-erbα is unique to the liver, yet is coupled to the clock since levels of Rev-erb? itself are circadian, meaning that it's only expressed at high levels in the liver at certain times of day.

The metabolic effects of Rev-erb? include a major role in the regulation of liver fat. Fatty liver has become a huge societal problem, and if untreated, can lead to liver inflammation (hepatitis) and life-threatening liver failure (cirrhosis). Fatty liver is highly related to obesity and diabetes, which are also major public health threats in the US and throughout the world.

"It is critical to find new ways to prevent or reverse the accumulation of fat in the liver," Lazar says. "Previously it was difficult to imagine how Rev-erb? could be a drug target for fatty liver if it was also involved in the maintaining the body's clock that controls sleep."

The Penn team's new findings show that the role of Rev-erbα in self-sustained control of the molecular clock across all tissues is different from that in the liver. "These two distinct modes of action may give Rev-erbα the ability to stabilize the circadian oscillations of clock genes, while coupling liver metabolism to daily environmental and metabolic changes," Lazar says. The coupling may occur through metabolites such as heme, the body's oxygen-carrying molecule, and other proteins, including an enzyme called histone deacetylase (HDAC), which are more critical for Rev-erb?'s metabolic function than its role in the clock.

"This raises the possibility that drugs that specifically affect Rev-erbα's interaction with metabolites or the HDAC enzyme, without disrupting the clock throughout the body could modulate liver metabolism while minimizing effects on the overall integrity of the circadian clock," he says. HDAC inhibitors are already in the clinic for certain forms of cancer. The researchers' hope is that this next chapter in Rev-erb??research can provide a new and more specific way to combat the growing epidemic of metabolic disease, especially fatty liver.

INFORMATION:

This study was made possible by the Functional Genomics Core and the Viral Vector Core of the Penn Diabetes Research Center (P30 DK19525), and the Penn Digestives Disease Center Morphology Core (P30 DK050306), as well as supported by the National Institutes of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK45586, K08 DK094968, R00 DK099443, R01 DK098542, F32 DK102284, F30 DK104513, T32 GM0008275), and the Cox Medical Research Institute.

Coauthors leading the study were Yuxiang Zhang and Bin Fang, along with Matthew J. Emmett, Manashree Damle, Zheng Sun (now at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston), Dan Feng, Sean M. Armour, Jarrett R. Remsberg, Jennifer Jager, Raymond E. Soccio, and David J. Steger, all from Penn.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $4.9 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine has been ranked among the top five medical schools in the United States for the past 17 years, according to U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $409 million awarded in the 2014 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania -- recognized as one of the nation's top "Honor Roll" hospitals by U.S. News & World Report; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center; Chester County Hospital; Penn Wissahickon Hospice; and Pennsylvania Hospital -- the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional affiliated inpatient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region include Chestnut Hill Hospital and Good Shepherd Penn Partners, a partnership between Good Shepherd Rehabilitation Network and Penn Medicine.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2014, Penn Medicine provided $771 million to benefit our community.

This news release is available in Japanese.

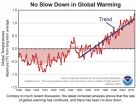

An analysis using updated global surface temperature data disputes the existence of a 21st century global warming slowdown described in studies including the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment. The new analysis suggests no discernable decrease in the rate of warming between the second half of the 20th century, a period marked by manmade warming, and the first fifteen years of the 21st century, a period dubbed a global warming "hiatus." Numerous studies have been done to explain the possible ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

Many species are migrating toward Earth's poles in response to climate change, and their habitats are shrinking in the process, researchers say. Two new reports focusing on marine organisms, which have been moving pole-ward at higher rates than terrestrial creatures, show how factors, including those not directly related to climate change, are limiting the ranges of corals and fish. Paul Muir and colleagues investigated 104 species of reef corals -- collectively known as the staghorn corals -- and confirmed the hypothesis ...

This news release is available in Japanese. With less than a drop of blood, a new technology called VirScan can identify all of the viruses that individuals have been exposed to over the course of their lives. Researchers used the screening technique with 569 people from around the world and found that, on average, their participants had been exposed to about 10 viral species over their lifetimes. VirScan provides a powerful and inexpensive tool for studying interactions between the human virome -- the collection of viruses known to infect humans, some of which don't ...

This news release is available in Japanese. Some of the world's last isolated tribes are emerging from the Amazon rainforest, forcing scientists and policymakers in South America to reconsider their policies regarding contact with such people. In this special package of news, Science correspondents Andrew Lawler and Heather Pringle report from Peru and Brazil, respectively -- two countries that are dealing with a spate of first encounters. Lawler describes contact between isolated tribespeople emerging from the forest and indigenous Peruvian villagers, who themselves ...

New technology developed by Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) researchers makes it possible to test for current and past infections with any known human virus by analyzing a single drop of a person's blood. The method, called VirScan, is an efficient alternative to existing diagnostics that test for specific viruses one at a time.

With VirScan, scientists can run a single test to determine which viruses have infected an individual, rather than limiting their analysis to particular viruses. That unbiased approach could uncover unexpected factors affecting individual ...

Friction is all around us, working against the motion of tires on pavement, the scrawl of a pen across paper, and even the flow of proteins through the bloodstream. Whenever two surfaces come in contact, there is friction, except in very special cases where friction essentially vanishes -- a phenomenon, known as "superlubricity," in which surfaces simply slide over each other without resistance.

Now physicists at MIT have developed an experimental technique to simulate friction at the nanoscale. Using their technique, the researchers are able to directly observe individual ...

A revolutionary power shift from internet giants such as Google to ordinary consumers is critically overdue, according to new research from a University of East Anglia (UEA) online privacy expert.

In a manifesto that ranges from "the right to be treated fairly on the internet" to finding a better, more nuanced approach to using the internet as an archive, Dr Paul Bernal of UEA's School of Law delves deeper into his research on the so-called 'right to be forgotten.' His paper, called 'A right to be remembered? Or the internet, warts and all,' will be presented today at ...

The red, itchy rash caused by varicella-zoster - the virus that causes chickenpox - usually disappears within a week or two. But once infection occurs, the varicella-zoster virus, or VZV, remains dormant in the nervous system, awaiting a signal that causes this "sleeper" virus to be re-activated in the form of an extremely unpleasant but common disease: herpes zoster, or shingles.

In a study recently published in PLOS Pathogens, scientists at Bar-Ilan University report on a novel experimental model that, for the first time, successfully mimics the "sleeping" and "waking" ...

Washington, DC-Unreliable estrogen measurements have had a negative impact on the treatment of and research into many hormone-related cancers and chronic conditions. To improve patient care, a panel of medical experts has called for accurate, standardized estrogen testing methods in a statement published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM).

The panel's recommendations are the first to address how improved testing methods can affect clinical care, and were developed based on discussions at an estrogen measurement workshop hosted ...

Women who exercise during pregnancy are less likely to have gestational diabetes, and the exercise also helps to reduce maternal weight gain, finds a study published on 3 June 2015 in BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

Gestational diabetes is one of the most frequent complications of pregnancy. It is associated with an increased risk of serious disorders such as pre-eclampsia, hypertension, preterm birth, and with induced or caesarean birth. It can have long term effects on the mother including long term impaired glucose tolerance and type ...