(Press-News.org) NEW YORK, NY (June 17, 2015) -- Infants and children who are given prescription acid-reducing medications face a substantially higher risk of developing Clostridium difficile infection, a potentially severe colonic disorder. The findings, reported by Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) researchers, suggest that pediatricians may do more harm than good by prescribing these drugs for children who have non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms such as occasional vomiting. The study was published recently in the online edition of Clinical Infectious Diseases.

"There's no question that acid-reducing medications alleviate heartburn in adults, but there's little evidence of benefit in healthy infants and younger children," said lead author Daniel E. Freedberg, MD, MS, assistant professor of medicine at CUMC. "Given our findings about the risk involved, pediatricians may hesitate before prescribing these drugs unless there is evidence of acid-related disease."

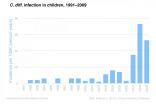

The rate of Clostridium difficile, often called C. diff., infection in children is increasing, with a ten-fold rise from 1991 to 2009. For unknown reasons, the infection has recently emerged as a problem in relatively healthy children lacking traditional risk factors.

C. diff. is a bacterium that can cause severe, even fatal, colonic inflammation. The most important risk factor for C. diff. infection is exposure to antibiotics. Antibiotics are thought to disturb the healthy balance of microbes in the intestinal tract, allowing C. diff. to flourish. Other risk factors for infection are inflammatory bowel disease, immune system compromise, advanced age, and hospitalization (since the bacterium is common in health-care settings).

Studies have shown that use of medications called proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) may contribute to C. diff. infection in adults. "The use of PPIs in the pediatric population is rising rapidly, which is why we felt it was important to find out if these medications are associated with an increased risk of C. diff. in children," said senior author Julian A. Abrams, MD, MS, Florence Irving Assistant Professor of Medicine at CUMC.

The study examined whether use of PPIs and another type of common acid-reducing medication--histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs)--might be contributing to the increased incidence of C. diff infection in children who have no known risk factors. "Previous studies have looked at the effects of these drugs on children with chronic illnesses that make them prone to C. diff. Less attention has been paid to relatively healthy children, including 'happy spitters' or infants who occasionally regurgitate but probably don't have anything truly wrong with them," said Dr. Freedberg.

The researchers examined the health records of children in The Health Improvement Network, a database of electronic medical records maintained by general practitioners throughout the United Kingdom, using data collected from 1995 to 2014. (Children with chronic conditions that might be associated with C. diff. infection were excluded.) The study identified 650 outpatients who had been diagnosed with C. diff. infection. Each patient's recent use of PPIs/H2RAs was compared with that of five age- and sex-matched controls who did not have C. diff infection.

The study found that 2.6% (17 of 650) of the children diagnosed with C. diff. infection had used

PPIs/H2RAs within 90 days, compared with just 0.3% (8 of 3,200) of the controls. In other words, use of acid-reducing drugs resulted in a seven-fold increase in risk for infection with C. diff. The effect was stronger for PPIs, which are more powerful than H2RAs.

The researchers suspect that, like antibiotics, acid reducing medications may increase the risk of C. diff. infection by altering the gastrointestinal microbiome.

"The microbiome in children is highly mutable up until age four or five," said Dr. Freedberg. "It is unknown whether changes during that formative period, due to antibiotics or PPIs, could alter the microbiome's ultimate trajectory."

INFORMATION:

The paper is titled, "Use of Acid Suppression Medication is Associated with Risk for C. difficile Infection in Infants and Children: A Population-Based Study." The senior author of the study is Julian A. Abrams, MD, MS, Florence Irving Assistant Professor of Medicine at CUMC. The other contributors are: Esi S. Lamousé-Smith (CUMC), Jenifer R. Lightdale (UMass Memorial Children's Medical Center, Worcester, MA), Zhezhen Jin (CUMC), and Yu-Xiao Yang (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA).

The study was funded by a Clinical Research Award from the American College of Gastroenterology, a mentored career development award through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences' Clinical and Translational Science Awards program (KL2 TR000081), and the Harold Amos Faculty Development Award from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Columbia University Medical Center provides international leadership in basic, preclinical, and clinical research; medical and health sciences education; and patient care. The medical center trains future leaders and includes the dedicated work of many physicians, scientists, public health professionals, dentists, and nurses at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, the Mailman School of Public Health, the College of Dental Medicine, the School of Nursing, the biomedical departments of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and allied research centers and institutions. Columbia University Medical Center is home to the largest medical research enterprise in New York City and State and one of the largest faculty medical practices in the Northeast. For more information, visit cumc.columbia.edu or columbiadoctors.org.

PITTSBURGH--The role of history in negotiations is a double-edged sword.

Although different sides can develop trust over time, there are also countless instances of prolonged feuds that developed because of conflicting histories. A prime example is World War II, which was fought in part to rectify perceived wrongs from the past. The phenomenon also extends to day-to-day situations such as sharing utility costs with a roommate or jockeying for position at grocery store checkout lanes.

New research published in the Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization examines ...

For the first time in the long and vaunted history of scanning electron microscopy, the unique atomic structure at the surface of a material has been resolved. This landmark in scientific imaging was made possible by a new analytic technique developed by a multi-institutional team of researchers, including scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab).

"We've developed a reasonably direct method for determining the atomic structure of a surface that also addresses the very challenging problem of buried interfaces," ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - For those wishing to lose weight and keep it off, here's a simple strategy that works: step on a scale each day and track the results.

A two-year Cornell study, recently published in the Journal of Obesity, found that frequent self-weighing and tracking results on a chart were effective for both losing weight and keeping it off, especially for men.

Subjects who lost weight the first year in the program were able to maintain that lost weight throughout the second year. This is important because studies show that about 40 percent of weight lost with any ...

WASHINGTON, D.C. - Alaska's melting glaciers are adding enough water to the Earth's oceans to cover the state of Alaska with a 1-foot thick layer of water every seven years, a new study shows.

The study found that climate-related melting is the primary control on mountain glacier loss. Glacier loss from Alaska is unlikely to slow down, and this will be a major driver of global sea level change in the coming decades, according to the study's authors.

"The Alaska region has long been considered a primary player in the global sea level budget, but the exact details on ...

Thanks to the extraordinary sensitivity of the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA), astronomers have detected what they believe is the long-sought radio emission coming from a supermassive black hole at the center of one of our closest neighboring galaxies. Evidence for the black hole's existence previously came only from studies of stellar motions in the galaxy and from X-ray observations.

The galaxy, called Messier 32 (M32), is a satellite of the Andromeda Galaxy, our own Milky Way's giant neighbor. Unlike the Milky Way and Andromeda, which are star-forming spiral ...

The percentage of patients with early-stage breast cancer undergoing breast-conserving therapy increased from 54.3 percent in 1998 to 60.1 percent in 2011, although nonclinical factors including socioeconomic demographics, insurance and the distance patients must travel to treatment facilities persist as key barriers to the treatment, according to a report published online by JAMA Surgery.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued a consensus statement in 1990 in support of this treatment method and that led to a substantial decline in rates of mastectomy and widespread ...

Sunscreen labels may still be confusing to consumers, with only 43 percent of those surveyed understanding the definition of the sun protection factor (SPF) value, according to the results of a small study published in a research letter online by JAMA Dermatology.

UV-A radiation is associated with skin aging, UV-B radiation is associated with sunburns, and exposure to both is a risk factor for skin cancer. In 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced new regulations for sunscreen labels to emphasize protection against both UV-A and UV-B radiation, now known ...

The risk for tic disorders, including Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders, increased with the degree of genetic relatedness in a study of families in Sweden, according to an article published online by JAMA Psychiatry.

While tic disorders are thought to be strongly familial and heritable, precise estimates of familial risk and heritability are lacking, although gene-searching efforts are under way. Limitations also exist in previous research.

David Mataix-Cols, Ph.D., of the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, and coauthors tried to overcome some of those limitations ...

Previous studies have led researchers to believe that individuals with social anxiety disorder/ social phobia have too low levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin. A new study carried out at Uppsala University, however, shows that the situation is exactly the opposite. Individuals with social phobia make too much serotonin. The more serotonin they produce, the more anxious they are in social situations.

Many people feel anxious if they have to speak in front of an audience or socialise with others. If the anxiety becomes a disability, it may mean that the person suffers ...

WASHINGTON - The ongoing outbreak in the Republic of Korea (South Korea) is an important reminder that the Middle East respiratory virus (MERS-CoV) requires constant vigilance and could spread to other countries including the United States. However, MERS can be brought under control with effective public health strategies, say two Georgetown University public health experts.

In a JAMA Viewpoint published online June 17, Georgetown public health law professor Lawrence O. Gostin and infectious disease physician Daniel Lucey outline strategies for managing the outbreak, ...