(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA--Telomeres, specialized ends of our chromosomes that dictate how long cells can continue to duplicate themselves, have long been studied for their links to the aging process and cancer. Now, a discovery at the Salk Institute shows that telomeres may be more central than previously thought to a self-destruct program in cells that prevents tumors, a function that could potentially be exploited to improve cancer therapies.

When cells replicate in a process called mitosis, their telomeres get a little shorter each time. Eventually, after many cell divisions, telomeres become critically short, signaling the cell to stop dividing. This normal process functions as a barrier against cancer. Cells that have defects in the signaling pathway, however, continue past this stage to self-destruct.

This process of cell destruction, called crisis, typically prevents genetically unstable or damaged cells from replicating. But many types of cancer cells circumvent crisis by protecting the telomeres to hamper the self-destruct signal and allow cells to continue to proliferate.

"We set out to understand the mechanism of cell death in crisis and found a much more active role of telomeres as barriers to tumor development than previously thought," says Jan Karlseder, Salk professor in the Molecular and Cell Biology Laboratory and senior author of the work. "It started when we saw that mitosis is longer in cells approaching crisis." The work is detailed in Nature.

While regular mitosis is typically about 30-45 minutes, cells about to go into crisis have a mitosis that lasts 2-20 hours or more. Observing this reminded the researchers of a 2012 discovery where they artificially lengthened the mitosis process. Typically, telomeres have a protein protecting them from being identified as damaged DNA by the cell and thus prevented them from proceeding to cell death. But during artificially lengthened mitosis, telomeres lost the protein, spurring a DNA damage signal that pushed the cells to self-destruct.

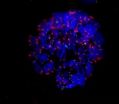

To their surprise, the scientists found that exactly the same thing was happening in the natural crisis state. In this new work, the researchers did real-time imaging of cells in a dish to track the cells' fate through one or more mitotic cycles. They found that a type of cellular stress called telomere fusion could evoke a prolonged mitosis and eventually crisis. Cells in this state lost their telomere-protecting protein and activated the self-destruct sequence.

"There was a long-standing hypothesis that turned out to be incorrect: that cells simply start to fuse chromosomes and break apart, generating instability and cell death," says Karlseder, who is also the holder of Salk's Donald and Darlene Shiley Chair. "What we show instead is it a much more targeted pathway that really only takes one cell cycle to cause crisis--it has nothing to do with the slow and steady accumulation of genomic instability."

Anthony Cesare, Head of the Genome Integrity Group at Children's Medical Research Institute in Australia and a contributor to the work, said the finding was very exciting and that it was unexpected to see how events early in the cell cycle, telomere fusions, are passed to a later stage of the cell cycle, mitosis. "This opens up new avenues for understanding how telomeres control cell growth and the implications of telomere biology in chemotherapy," he says.

Several chemotherapies--such as Taxol for breast cancer--seek to stop cancer by interrupting mitosis so cancer cells can no longer divide. The researchers hypothesize that they can enhance these mitotic inhibitors by, for example, deprotecting telomeres first to make the cells more susceptible to drugs. It might also be possible to see if cells from a particular tumor had shorter or deprotected telomeres and, if so, expect that tumor to be much more sensitive to mitotic inhibitors.

"The pathway we've found challenges a long-held hypothesis on cellular behavior during early tumor formation," says Makoto Hayashi, a researcher at the Hakubi Center for Advanced Research at Kyoto University and first author of the new work. "Comprehensive understanding of the pathway will hopefully provide us a novel method of early tumor diagnosis and a therapeutic opportunity for very early stage of cancer."

The lab is currently working with Deborah Kado, MD, MS, at the University of California, San Diego to test these theories in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer.

INFORMATION:

Authors of the study are Makoto T. Hayashi of Kyoto University, Anthony J. Cesare at the Children's Medical Research Institute, and Teresa Rivera and Jan Karlseder of the Salk Institute.

This work was funded by the Human Frontier Science Program and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Postdoctoral Fellowships for Research Abroad, the National Institutes of Health, the Donald and Darlene Shiley Chair, the Highland Street Foundation, the Fritz B. Burns Foundation, the Emerald Foundation, and the Glenn Center for Research on Aging.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probes fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, MD, the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

The prospect of finding ocean-bearing exoplanets has been boosted, thanks to a pioneering new study.

An international team of scientists, including from the University of Exeter, has discovered an immense cloud of hydrogen escaping from a Neptune-sized exoplanet.

Such a phenomena not only helps explain the formation of hot and rocky 'super-earths', but also may potentially act as a signal for detecting extrasolar oceans. Scientists also believe they can use the discovery to envisage the future of Earth's atmosphere, four billion years from today.

The ground-breaking ...

DETROIT - Urban gardens are becoming more commonplace across Detroit and other major urban cities throughout the United States. These gardens offer a source of free or inexpensive healthy food for the public and educate community members about food production and rehabilitating the local ecosystem. The revolution of urban agriculture has the potential to address many economic, environmental and personal health issues.

With urban agriculture gaining popularity for improving local and sustainable food systems, the question of food safety has become a growing concern. To ...

The Impact Factors and journal metrics for the range of molecular bioscience journals published by Portland Press, the knowledge hub for life sciences, have been announced. The 2015 Release of Journal Citation Reports® (Source: 2014 Web of ScienceTM Data) shows an increase in article influence scores indicating that the research being published and cited in Portland Press journals carries influence scores above the average in its field.

The announcement of these metrics comes in the middle of an exciting year for Portland Press. Having just migrated all its journals ...

The initial results of a study suggested that children born by cesarean section were 21 percent more likely to be diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder but that association did not hold up in further analysis of sibling pairs, implying the initial association was not causal and was more likely due to unknown genetic or environmental factors, according to an article published online by JAMA Psychiatry.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is thought to affect about 0.62 percent of children worldwide, although estimates in the United States have been closer to 1.5 percent. ...

The notion that geography often shapes economic and political destiny has long informed the work of economists and political scholars. Now a study led by medical scientists at Johns Hopkins reveals how geography also appears to affect the very survival of people with end-stage kidney disease in need of dialysis.

"If you are a person with kidney failure in Texas you're in trouble, but if you're in New England you're golden, and that's profoundly troubling because the quality of care shouldn't be predicated on your ZIP code," says senior investigator Mahmoud Malas, M.D., ...

(BOSTON) - Antibiotics are the mainstay in the treatment of bacterial infections, and together with vaccines, have enabled the near eradication of infectious diseases like tuberculosis, at least in developed countries. However, the overuse of antibiotics has also led to an alarming rise in resistant bacteria that can outsmart antibiotics using different mechanisms. Some pathogenic bacteria are thus becoming almost untreatable, not only in underdeveloped countries but also in modern hospital settings.

While some researchers seek to develop antibiotics with new mechanisms ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - A new study performed by researchers at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center shows that when it comes to overuse injuries in high school sports, girls are at a much higher risk than boys. Overuse injuries include stress fractures, tendonitis and joint pain, and occur when athletes are required to perform the same motion repeatedly.

The study published in April in the Journal of Pediatrics. Dr. Thomas Best analyzed 3,000 male and female injury cases over a seven year period across 20 high school sports such as soccer, volleyball, gymnastics ...

PITTSBURGH, June 24 -- Moving closer to the possibility of "materials that compute" and wearing your computer on your sleeve, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh Swanson School of Engineering have designed a responsive hybrid material that is fueled by an oscillatory chemical reaction and can perform computations based on changes in the environment or movement, and potentially even respond to human vital signs. The material system is sufficiently small and flexible that it could ultimately be integrated into a fabric or introduced as an inset into a shoe.

Anna ...

Researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have, for the first time, uncovered the complex interdependence and orchestration of metabolic reactions, gene regulation, and environmental cues of clostridial metabolism, providing new insights for advanced biofuel development.

"This work advances our fundamental understanding of the complex, system-level process of clostridial acetone-butanol-ethanol (ABE) fermentation," explained Ting Lu, an assistant professor of bioengineering at Illinois. "Simultaneously, it provides a powerful tool for guiding strain ...

Alexandria, VA - Humans depend on copper for everything from electrical wiring to water pipes. To meet demand, the metal has been largely mined from Porphyry Copper Deposits (PCDs). For decades, scientists generally agreed upon the geological processes behind PCD formation; now EARTH Magazine examines two new studies that suggest alternatives to these long-held understandings.

From enriched pulses of magmatic fluids creating copper concentrations, to remelted crust allowing deeper PCDs to rise up to shallower depths, these conclusions may better inform geologists about ...