(Press-News.org) AURORA, Colo. (July 15, 2015) - Physicians at the University of Colorado School of Medicine on the Anschutz Medical Campus have published research that suggests a safe and lower-cost way to diagnose and treat problems in the upper gastrointestinal tract of children.

The researchers assessed the effectiveness of unsedated transnasal endoscopy (TNE) in evaluating pediatric patients with potentially chronic problems in their esophagus, which is the tube that connects the patient's mouth to the stomach. The research team included Joel A. Friedlander, DO, MA-Bioethics, Jeremy Prager, MD, Emily Deboer, MD, and Robin Deterding MD, of the Aerodigestive Program, working with the Gastrointestinal Eosinophilic Disorders Program at Children's Hospital Colorado.

In cases of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), patients develop a buildup of a type of white blood cells that can inflame or injure the tissue in the esophagus. The buildup of white blood cells can be caused by a reaction to foods, allergens or acid reflux and it can lead to difficulty swallowing and other problems.

Typically, children are evaluated with a procedure that requires sedation known as EGD (esophagogastroduodenoscopy), where a long flexible lighted tube is guided through a sedated patient's mouth and throat to examine inside of organs and detect abnormalities. Friedlander and his colleagues evaluated whether the use of a much thinner scope inserted through the nose rather than the mouth without the risks and costs of anesthesia could be as effective in evaluating a patient.

Between March 2014 and January 2015, 21 patients aged 8 to 17 were enrolled in the study. The research team reviewed the quality of biopsy specimens and the satisfaction and comfort of patients with the procedure.

The result was that TNE "is safe, is preferred by patients and parents alike, and has the potential to dramatically reduce costs," with esophagus biopsies that are as good as those from EGD procedures, the authors wrote in an article published in the journal Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The cost and the procedure's length of time are significantly reduced because the patient does not need to be sedated to perform TNE. Topical anesthetics were used and patients were equipped with video goggles to watch movies or television programs to distract them during the process.

According to the study, the patients and their parents expressed a high level of satisfaction with the procedure because of "the lack of anesthesia, the presence of parents during the procedure, the limited duration of the procedure, rapid recovery, and improvement in their quality of life."

Based on their analysis, the researchers found that the procedure has the promise of significantly reducing costs. The usual charge for EGD, which includes anesthesia, is $9,391, while TNE would be $3,548. For 100 procedures, the savings to the health care system would be $584,300.

"Our study provides strong support for larger studies to validate this approach," said Friedlander. "This technique has the potential to significantly improve the lives of children with EoE in a safer, cost-effective, and efficacious manner."

INFORMATION:

Friedlander and 10 other faculty members of the School of Medicine are authors of the study.

About the University of Colorado School of Medicine

Faculty at the University of Colorado School of Medicine work to advance science and improve care. These faculty members include physicians, educators and scientists at University of Colorado Health, Children's Hospital Colorado, Denver Health, National Jewish Health, and the Denver Veterans Affairs Medical Center. The school is located on the Anschutz Medical Campus, one of four campuses in the University of Colorado system. To learn more about the medical school's care, education, research and community engagement, visit its web site.

Contact: Mark Couch, 303-724-5377, mark.couch@ucdenver.edu

The human genome encodes roughly 20,000 genes, only a few thousand more than fruit flies. The complexity of the human body, therefore, comes from far more than just the sequence of nucleotides that comprise our DNA, it arises from modifications that occur at the level of gene, RNA and protein.

In a new study, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine show how one of these modifications, which occurs after RNA is translated into proteins, has the power to greatly influence the function of an enzyme called PRPS2, which is required for ...

Athens, Ga. - Researchers from the University of Georgia have determined that various freshwater sources in Georgia, such as rivers and lakes, could feature levels of salmonella that pose a risk to humans. The study is featured in the July edition of PLOS One.

Faculty and students from four colleges and five departments at UGA partnered with colleagues from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Georgia Department of Public Health to establish whether or not strains of salmonella exhibit geographic trends that might help to explain differences in rates ...

DURHAM, N.C. - Children with even mild or passing bouts of depression, anxiety and/or behavioral issues were more inclined to have serious problems that complicated their ability to lead successful lives as adults, according to research from Duke Medicine.

Reporting in the July 15 issue of JAMA Psychiatry, the Duke researchers found that children who had either a diagnosed psychiatric condition or a milder form that didn't meet the full diagnostic criteria were six times more likely than those who had no psychiatric issues to have difficulties in adulthood, including ...

Children with psychiatric problems were more likely to have health, legal, financial and social problems as adults even if their psychiatric disorders did not persist into adulthood and even if they did not meet the full diagnostic criteria for a disorder, according to an article published online by JAMA Psychiatry.

Neuropsychiatric disorders among young people ages 10 to 24 are a leading cause of disease burden globally. Unlike many chronic physical health problems, most psychiatric disorders are first diagnosed in childhood, which allows the disorder to affect a person's ...

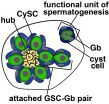

PHILADELPHIA - Stem cells are key for the continual renewal of tissues in our bodies. As such, manipulating stem cells also holds much promise for biomedicine if their regenerative capacity can be harnessed. However, understanding how stem cells govern normal tissue renewal is a field still in its infancy.

Researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania are making headway in this area by studying stem cells in their natural environment in an organism. Stem cell populations reside in areas called niches deep within different types of organs. ...

States with more restrictive alcohol policies and regulations have lower rates of self-reported drunk driving, according to a new study by researchers at the Boston University schools of public health and medicine and the University of Minnesota School of Public Health.

The research team assigned each state an "alcohol policy score," based on an aggregate of 29 alcohol policies, such as alcohol taxation and the use of sobriety checkpoints. Each 1 percentage point increase in the score was found to be associated with a 1 percent decrease in the likelihood of impaired driving, ...

Final results of the randomized intergroup EORTC, LYSA (Lymphoma Study Association), FIL (Fondazione Italiana Linfomi) H10 trial presented at the 13th International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma in Lugano, Switzerland, on 19 June 2015 show that early FDG-PET ( 2-deoxy-2[F-18]fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography) adapted treatment improves the outcome of early FDG-PET-positive patients with stages I/II Hodgkin lymphoma.

Dr. John Raemaekers of the Radboud University Medical Center Nijmegen and the Rijnstate Hospital Arnhem, The Netherlands, and EORTC principal ...

HOUSTON - (July 15, 2015) - Three-dimensional structures of boron nitride might be the right stuff to keep small electronics cool, according to scientists at Rice University.

Rice researchers Rouzbeh Shahsavari and Navid Sakhavand have completed the first theoretical analysis of how 3-D boron nitride might be used as a tunable material to control heat flow in such devices.

Their work appears this month in the American Chemical Society journal Applied Materials and Interfaces.

In its two-dimensional form, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), aka white graphene, looks ...

A University of Toronto research team has discovered new details about a key gene involved in ALS, perhaps humanity's most puzzling, intractable disease.

In this fatal disorder with no effective treatment options, scientists (including members of U of T) achieved a major breakthrough in 2011 when they discovered mutations in the gene C9orf72, as the most frequent genetic cause of ALS and frontotemporal dementia. But little was known about how this gene and its related protein worked in the cell.

To solve this problem, Professor Janice Robertson and her team at the ...

Sapphirina, or sea sapphire, has been called "the most beautiful animal you've never seen," and it could be one of the most magical. Some of the tiny, little-known copepods appear to flash in and out of brilliantly colored blue, violet or red existence. Now scientists are figuring out the trick to their hues and their invisibility. The findings appear in the Journal of the American Chemical Society and could inspire the next generation of optical technologies.

Copepods are tiny aquatic crustaceans that live in both fresh and salt water. Some males of the ocean-dwelling ...