(Press-News.org) From an early age, human infants are able to produce vocalisations in a wide range of emotional states and situations - an ability felt to be one of the factors required for the development of language. Researchers have found that wild bonobos (our closest living relatives) are able to vocalize in a similar manner. Their findings challenge how we think about the evolution of communication and potentially move the dividing line between humans and other apes.

Animal vocalisations are usually made in relatively narrow behavioural contexts linked to emotional states, such as to express aggressive motivation or to warn about potential predators. In contrast, humans exhibit 'functional flexibility' when vocalizing in a variety of situations.

Researchers from the University of Birmingham, UK and the University of Neuchatel, Switzerland, conducted research on wild bonobos and found that in this species individuals produce a call type, known as the 'peep', across a range of positive, negative and neutral situations, such as during feeding, travel, rest, aggression, alarm, nesting and grooming. Peeps are high-pitched vocalisations which are short in duration and produced with a closed mouth.

They found broad similarity in the acoustic structure across different contexts suggesting contextual flexibility in this call. Similar to human infants, recipients therefore have to make pragmatic inferences about the meaning of this call across contexts.

Author Zanna Clay said that the findings show that "more research needs to be done on our great ape relatives before we can make conclusions about human uniqueness. The more we look, the more continuity we find among animals and humans"

The type of functional flexibility they observed in bonobos could represent an important evolutionary transition from functionally fixed animal vocalisations towards flexible human vocalisations, which seems to have appeared some 6-10 million years ago in the shared common ancestor between humans and great apes. It appears that many of the core features of human language have deep roots in the primate lineage.

INFORMATION:

About PeerJ:

PeerJ is an Open Access publisher of peer reviewed articles, which offers researchers a lifetime publication plan, for a single low price, providing them with the ability to openly publish all future articles for free. PeerJ is based in San Francisco, CA and London, UK and can be accessed at https://peerj.com/. PeerJ's mission is to help the world efficiently publish its knowledge.

All works published in PeerJ are Open Access and published using a Creative Commons license (CC-BY 4.0). Everything is immediately available--to read, download, redistribute, include in databases and otherwise use--without cost to anyone, anywhere, subject only to the condition that the original authors and source are properly attributed.

PeerJ has an Editorial Board of over 1,000 respected academics, including 5 Nobel Laureates. PeerJ was the recipient of the 2013 ALPSP Award for Publishing Innovation.

PeerJ Media Resources (including logos) can be found at: https://peerj.com/about/press/

Media Contacts

For the authors: Zanna Clay, email: z.clay@bham.ac.uk, Phone: +44 7967 567 111 (UK)

For PeerJ: email: press@peerj.com , https://peerj.com/about/press/

Note: If you would like to join the PeerJ Press Release list, visit: http://bit.ly/PressList

Abstract (from the article):

A shared principle in the evolution of language and the development of speech is the emergence of functional flexibility, the capacity of vocal signals to express a range of emotional states independently of context and biological function. Functional flexibility has recently been demonstrated in the vocalisations of pre-linguistic human infants, which has been contrasted to the functionally fixed vocal behaviour of non-human primates. Here, we revisited the presumed chasm in functional flexibility between human and non-human primate vocal behaviour, with a study on our closest living primate relatives, the bonobo (Pan paniscus). We found that wild bonobos use a specific call type ("peeps") across a range of contexts that cover the full valence range (positive-neutral-negative) in much of their daily activities, including feeding, travel, rest, aggression, alarm, nesting and grooming. Peeps were produced in functionally flexible ways in some contexts, but not others. Crucially, calls did not vary acoustically between neutral and positive contexts, suggesting that recipients take pragmatic information into account to make inferences about call meaning. In comparison, peeps during negative contexts were acoustically distinct. Our data suggest that the capacity for functional flexibility has evolutionary roots that predate the evolution of human speech. We interpret this evidence as an example of an evolutionary early transition away from fixed vocal signalling towards functional flexibility.

Washington, DC-- Climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions will alter the way that Americans heat and cool their homes. By the end of this century, the number of days each year that heating and air conditioning are used will decrease in the Northern states, as winters get warmer, and increase in Southern states, as summers get hotter, according to a new study from a high school student, Yana Petri, working with Carnegie's Ken Caldeira. It is published by Scientific Reports.

"Changes in outdoor temperatures have a substantial impact on energy use inside," Caldeira ...

A team of scientists believe they have shown that memories are more robust than we thought and have identified the process in the brain, which could help rescue lost memories or bury bad memories, and pave the way for new drugs and treatment for people with memory problems.

Published in the journal Nature Communications a team of scientists from Cardiff University found that reminders could reverse the amnesia caused by methods previously thought to produce total memory loss in rats. .

"Previous research in this area found that when you recall a memory it is sensitive ...

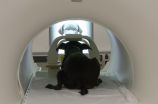

Dogs have a specialized region in their brains for processing faces, a new study finds. PeerJ is publishing the research, which provides the first evidence for a face-selective region in the temporal cortex of dogs.

"Our findings show that dogs have an innate way to process faces in their brains, a quality that has previously only been well-documented in humans and other primates," says Gregory Berns, a neuroscientist at Emory University and the senior author of the study.

Having neural machinery dedicated to face processing suggests that this ability is hard-wired ...

Trauma may cause distinct and long-lasting effects even in people who do not develop PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), according to research by scientists working at the University of Oxford's Department of Psychiatry. It is already known that stress affects brain function and may lead to PTSD, but until now the underlying brain networks have proven elusive.

Led by Prof Morten Kringelbach, the Oxford team's systematic meta-analysis of all brain research on PTSD is published in the journal Neuroscience and Biobehavioural Reviews. The research is part of a larger ...

CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA (AUGUST 4, 2015). Researchers at the University of Virginia (UVa) examined the number and severity of subconcussive head impacts sustained by college football players over an entire season during practices and games. The researchers found that the number of head impacts varied depending on the intensity of the activity. Findings in this case are reported and discussed in "Practice type effects on head impact in collegiate football," by Bryson B. Reynolds and colleagues, published today online, ahead of print, in the Journal of Neurosurgery.

The researchers ...

August 4, 2015 -- Treating maternal psychiatric disorder with commonly used antidepressants is associated with a lower risk of certain pregnancy complications including preterm birth and delivery by Caesarean section, according to researchers at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University Medical Center, and the New York State Psychiatric Institute. However, the medications -- selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs -- resulted in an increased risk of neonatal problems. Findings are published online in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

"To ...

Chestnut Hill, MA (August 4, 2015): It's been said that "Those who don't know history are doomed to repeat it," but even if you know your own history, that doesn't necessarily help you with self-control. New research published in the Journal of Consumer Psychology shows the effectiveness of memory in improving our everyday self-control decisions depends on what we recall and how easily it comes to mind.

"Despite the common belief that remembering our mistakes will help us make better decisions in the present," says the study's lead author, Hristina Nikolova, Ph.D., an ...

PHILADELPHIA - The roughly nine million Americans who rely on prescription sleeping pills to treat chronic insomnia may be able to get relief from as little as half of the drugs, and may even be helped by taking placebos in the treatment plan, according to new research published today in the journal Sleep Medicine by researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Their findings starkly contrast with the standard prescribing practices for chronic insomnia treatment.

The findings, which advocate for a dosing strategy of smaller and fewer ...

Research on alcohol-use disorders consistently shows problem drinking decreases as we age. Also called, "maturing out," these changes generally begin during young adulthood and are partially caused by the roles we take on as we become adults. Now, researchers collaborating between the University of Missouri and Arizona State University have found evidence that marriage can cause dramatic drinking reductions even among people with severe drinking problems. Scientists believe findings could help improve clinical efforts to help these people, inform public health policy changes ...

Here's a quick task: Take a look at the sentences below and decide which is the most effective.

(1) "John threw out the old trash sitting in the kitchen."

(2) "John threw the old trash sitting in the kitchen out."

Either sentence is grammatically acceptable, but you probably found the first one to be more natural. Why? Perhaps because of the placement of the word "out," which seems to fit better in the middle of this word sequence than the end.

In technical terms, the first sentence has a shorter "dependency length" -- a shorter total distance, in words, between ...