Reporting their data Aug. 6 in the journal Molecular Cell, scientists at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center say the new technology - called SpDamID - could allow scientists to answer basic questions about tissue development and disease that existing technology cannot address.

"With further development this technology has the potential to give investigators glimpses into biological problems that cannot be answered with existing tools" says Raphael Kopan, PhD, senior author and director of Developmental Biology at Cincinnati Children's. "This method has been transformative for our research."

Cellular processes are largely regulated by the combined action of multiple transcription factors - proteins that bind to specific DNA sites on chromosomes to deliver directions on what the cell is supposed to be and do. Disease processes often begin with mutations in the transcription factor, or in the DNA they bind to inside the nucleus of cells to regulate the complex interplay of genes needed for a healthy functioning body. These genetic miscues can cause cells to grow out of control, evade the immune system, or fail to execute essential functions needed to maintain health.

To understand defective disease process, investigators need to track where and how transcription factors bind to DNA to identify the differences between healthy and diseased cells. Given the size of the human genome - all contained within the infinitesimal micro-world in each cell - current research methods for tracking protein-DNA binding can be tedious, time-consuming and not always conclusive, according to the researchers.

One current method commonly used today is called chromatin immunoprecipitation, combined with next-generation gene sequencing (ChIP-seq). The limitation of ChIP-seq is that it cannot deliver a conclusive picture of transcription factor binding in a single cell because it samples events in a population after the cells have been exposed to various toxic chemicals. Any conclusions regarding occupancy of a single strand of DNA by different transcription factors is based on inference.

Developed by Kopan and Cincinnati Children's colleague Matthew Hass, PhD, the researchers report that SpDamID technology is a precise, fast and efficient method for making these comparisons. SpDamID also is uniquely able to identify DNA bound by more than one protein, often a critical step in gene regulation.

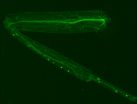

SpDamID marks DNA in the living cells and only when the two tagged proteins bind in proximity to each other on the same DNA strand, the authors report. The technique is based on an earlier method called DamID. Dam is an acronym of an enzyme called DNA adenine methyltransferase.

The method developed by Hass and Kopan involves splitting Dam in half to create two inactive halves of what had been a functioning protein. Researchers then connect the inactive halves of DAM to proteins of interest they suspect bind near each other, or that even bind to each other in order to bind DNA. This allows the Dam enzyme to become active again and mark any locations in chromosomes where the two proteins interact.

Because this reaction occurs only when both proteins are in the same cell and on the same piece of DNA, there is no ambiguity in determining the simultaneous binding of the protein pair. In addition, the method requires fewer cells than ChIP-seq, allowing investigation of processes that are limited in duration or occur in small cell populations.

To demonstrate the capabilities of SpDamID in the current study, the authors analyzed Notch-mediated transcriptional activation in mouse kidney progenitor cells (mK4 cells). Notch - a critical molecule involved in the development and maintenance of most of tissues and organs - has been a focus of the Kopan laboratory since 1990. Defects in this molecule play a central role in multiple diseases, including a genetic kidney disorder called Alagille syndrome, cancer, CADASIL, and multiple sclerosis.

Hass said SpDamID was developed to answer a number of important questions about Notch transcriptional regulation in the nuclei of mK4 cells. Notch is a protein that does not bind directly to DNA. When Notch is switched on, it binds to DNA only after binding to a DNA-binding partner. In turn, Notch and its partner recruit many other proteins to turn transcription "on" at several key locations.

The authors report that when the inactive halves of DAM attached to Notch and its partners rejoined, they reactivated and allowed the marking of the bound DNA in kidney cells. This let researchers identify all of the key locations where Notch was present. Additionally, these sites were close to sites where another transcription factor called Runx1 was landing. The authors used SpDamID to show that Notch and Runx1 were binding to the same chromosome in the same cell, evidence they could not have collected with ChIP-seq.

Kopan and Hass said the technology should allow investigators to start comparing the binding of any transcription factor in normal and disease cells - which could offer new insights about what triggers the conditions they study.

The authors emphasize that new research techniques are reported almost daily, and the full impact of SpDamID on the research community will have to be judged after several years have passed. They said SpDamID does provide investigators with a tool capable of addressing questions no other research tool can at present.

INFORMATION:

The study was supported primarily by funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act Grant (1RC1NS068277-01) and the National Institutes of Health (R01CA163653-01A1).

About Cincinnati Children's

Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center ranks third in the nation among all Honor Roll hospitals in U.S.News and World Report's 2015 Best Children's Hospitals. It is also ranked in the top 10 for all 10 pediatric specialties, including a #1 ranking in pulmonology and #2 in cancer and in nephrology. Cincinnati Children's, a non-profit organization, is one of the top three recipients of pediatric research grants from the National Institutes of Health, and a research and teaching affiliate of the University of Cincinnati's College of Medicine. The medical center is internationally recognized for improving child health and transforming delivery of care through fully integrated, globally recognized research, education and innovation. Additional information can be found at http://www.cincinnatichildrens.org. Connect on the Cincinnati Children's blog, via Facebook and on Twitter.