The harmful molecules -- dicarbonyls -- are breakdown products of glucose that interfere with infection-controlling antimicrobial peptides known as beta-defensins. The Case Western Reserve team discovered how two dicarbonyls -- methylglyoxal (MGO) and glyoxal (GO) -- alter the structure of human beta-defensin-2 (hBD-2) peptides, hobbling their ability to fight inflammation and infection.

Their laboratory in vitro findings, which appear this week in PLOS ONE, could ultimately contribute important insights into developing and enhancing antimicrobial peptide drugs for people with diabetes who have hard-to-control infections and wounds that are slow to heal.

"If our findings hold up in future in vivo animal experiments and in human tissues, we will have solid evidence for how this dicarbonyl mechanism works in the setting of uncontrolled diabetes to weaken hBD-2 function, and that of other beta-defensins," said senior author Wesley M. Williams, PhD, who conducted the research in the Department of Biological Sciences, Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine.

First author Janna Kiselar, PhD, concurs. "Our in vitro findings alone could have a significant impact on development of more effective antimicrobial treatment strategies for patients with uncontrolled diabetes," said Kiselar, the assistant director and instructor at the Center for Proteomics and Bioinformatics, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. "The findings also emphasize the importance of lowering high blood sugar and keeping it under control."

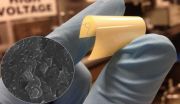

Critical to the research was the mass spectral analysis (LCMSMS) and the in vitro, petri dish experiments at the lab bench. Mass spectral analysis involves interpreting a pattern in the distribution of ions by a body of matter, known as mass, and then individual molecules are identified within a range (or segment) of the mass, known as mass spectra.

Kiselar and Williams collaborated on experiments that compared the mass spectra, the bacterial-killing potential and the immune cell-attracting ability of dicarbonyl-treated hBD-2 with untreated hBD-2. This beta-defensin was initially exposed to the activities of two key dicarbonyls -- MGO and GO, both of which are known to increase in humans with high blood sugar. Mass spectral analysis showed that MGO was the more reactive of the two dicarbonyls, so subsequent bacteria-killing and chemotactic experiments were performed by exposing hBD-2 to MGO.

First the investigators compared the mass spectra for the dicarbonyl-exposed hBD-2 with untreated hBD-2. In the dicarbonyl-exposed hBD-2, they found that in addition to binding to several other amino acid residues, the dicarbonyl irreversibly binds to two positively charged arginine amino acids located near the surface of the hBD-2 peptide. The importance of positive or negative charges in a protein is that they can significantly influence the protein's function.

The effect of these arginine charges is substantial because they may influence how that protein interacts with other compounds and with cells, including bacteria. Increasing or decreasing the positive charge or negative charge in a protein could alter the function of that protein, depending on where those charges are located within the protein.

Next, the investigators compared dicarbonyl-treated hBD-2 to untreated hBD-2 in their ability to kill gram-negative bacteria. The untreated hBD-2 is quite effective in killing gram-negative bacteria, while dicarbonyl-exposed hBD-2 greatly impaired this defensin's ability to stop the onslaught of bacteria.

"In the petri dish of hBD-2 treated with dicarbonyl, we saw a roughly 50 percent reduction in the ability of hBD-2 to inhibit growth or kill the bacteria," Williams said. "It was a significant loss of function, and we saw this effect quite visually. Experiments were repeated multiple times using several bacterial strains, and we found a loss of function in all cases. It establishes that the antimicrobial function was being significantly impeded by the MGO dicarbonyl."

Finally, investigators examined the effects of MGO on hBD-2's critical role in an early-stage immune system response. Defensins such as hBD-2 not only inhibit entry into the body of microbes, such as bacteria and viruses, but they also post an alert to the immune system about the invader. The adaptive and innate features of the immune system can then identify the microbe for destruction now and into the future. Defensins work, in part, through chemoattraction of specific immune cells in order to activate the next stage of the immune response, called adaptive immunity.

To test the chemoattraction effect, Kiselar and Williams, in collaboration with George Dubyak, PhD, professor of physiology and biophysics, examined the effects of dicarbonyl on the chemoattraction capabilities of hBD-2. Usually, specific human immune cells are responsive and attracted by hBD-2. In the cells exposed to the MGO-treated hBD-2, the beta-defensin lost much of its ability to initiate chemoattraction.

As for next steps in the research, studies in animal models or human tissues will be needed to verify the in vitro findings about the harmful effects of dicarbonyl on the beta-defensin family of antimicrobial peptides, particularly among people with diabetes who have uncontrolled high blood sugar, commonly known as hyperglycemia. Additionally, human antimicrobial peptides other than the beta-defensins may also be affected negatively by a dicarbonyl attack, thus reducing both their antimicrobial and chemoattractive functions.

"The body does have defense mechanisms against molecules such as dicarbonyl, but with a chronic disease such as diabetes, the effectiveness of these defense mechanisms responsible for keeping dicarbonyl levels under control may be overwhelmed," Williams said. "The result may be dicarbonyl accumulation that could eventually overwhelm the ability of beta-defensins to effectively control inflammation and infection."

For now, control of blood sugar through diet and medicine can hold the dicarbonyl-beta defensins dynamic at bay. The need is great for the development of effective antimicrobial peptides and antihyperglycemia drugs and medications with fewer or more tolerable side effects that would help to neutralize the dicarbonyl pathway.

"Approximately 29.1 million Americans -- 9.3 percent -- have diabetes," Williams said. "These are individuals who might benefit from improved efficacy of beta-defensin function. Exactly how this will be done remains ill defined at present, but blood sugar control, either through life-style changes (exercise and diet) or medication, would be a logical approach to minimizing infection in diabetes. We hope our findings will contribute to a solution."

INFORMATION:

Joining Kiselar and Williams in this research were contributing authors Xiaowei Wang, Department of Periodontics, Case Western Reserve School of Dental Medicine; George R. Dubyak and Caroline El Sanadi, Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Case Western Reserve; Santosh K. Ghosh, Department of Biological Sciences, Case Western Reserve School of Dental Medicine; and Kathleen Lundberg, Center for Proteomics and Bioinformatics, Case Western Reserve School of Medicine.

This research was supported by a pilot award from the School of Medicine's Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland.

About Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine

Founded in 1843, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine is the largest medical research institution in Ohio and is among the nation's top medical schools for research funding from the National Institutes of Health. The School of Medicine is recognized throughout the international medical community for outstanding achievements in teaching. The School's innovative and pioneering Western Reserve2 curriculum interweaves four themes--research and scholarship, clinical mastery, leadership, and civic professionalism--to prepare students for the practice of evidence-based medicine in the rapidly changing health care environment of the 21st century. Nine Nobel Laureates have been affiliated with the School of Medicine.

Annually, the School of Medicine trains more than 800 MD and MD/PhD students and ranks in the top 25 among U.S. research-oriented medical schools as designated by U.S. News & World Report's "Guide to Graduate Education."

The School of Medicine's primary affiliate is University Hospitals Case Medical Center and is additionally affiliated with MetroHealth Medical Center, the Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and the Cleveland Clinic, with which it established the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University in 2002. http://case.edu/medicine