(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH-- In the era of launching Kickstarter campaigns to pay for just about anything, Carnegie Mellon University ethicists warn that the trend of patients funding their own clinical trials may do more harm than good.

CMU's Danielle Wenner and Alex John London and McGill University's Jonathan Kimmelman co-wrote a column in Cell Stem Cell outlining how patient-funded trials may seem like a beneficial new way to involve more patients in research and establish new funding opportunities, but instead they threaten scientific rigor, relevance, efficiency and fairness.

"Patient-funded trials look like they could be a boon to science by attracting previously untapped resources to research," said Wenner, the lead author and assistant professor of philosophy in the Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences. "The problem with this model is that it lacks mechanisms to ensure that research is grounded in good science. Rather than increasing the pace of biomedical progress, it may delay innovation through the diversion of resources, and ultimately harm the very people it is intended to help."

Wenner, London and Kimmelman believe that crowdfunding trials are gaining popularity partially due to limited funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and other agencies. People also are more willing to explore alternate funding models.

"Patients with diseases that do not have effective treatments and interventions are desperate to see the pace of science move more quickly or get fast access to something that will help them immediately. Similarly, researchers who can't get NIH funding are turning to crowdfunding," said London, professor of philosophy and director of CMU's Center for Ethics and Policy.

But, patient-funded trials often attract people who are seriously ill and therefore willing to take large risks. They also allow clinics to pop-up that are clearly motivated by profit under the guise of offering new interventions, some of which do not have sufficient basic science findings to support them.

"Many patients and patient advocacy groups think the current funding system is too conservative," London said. "But, it's a system that directs the individual interests of various parties toward one goal. For example, drug companies can't make money until their intervention passes requirements set by the FDA to ensure that it actually works. Patient-funding trials sidestep such mechanisms."

Wenner, London and Kimmelman suggest incentives are needed to align patient-funded trials and clinics with the production of solid research. They believe this could be done through large-scale policies that provide scientific and ethical oversight and by mandates from a variety of different parties, such as academic medical centers requiring peer review of all research trials. Another option is the implementation of accreditation requirements for health care facilities to encourage them to use appropriate methods for scientific review and ethical considerations.

"The bottom line is that patient-funded models are a novel funding model, but they threaten to de-stabilize a system that ensures high quality results," London said.

INFORMATION:

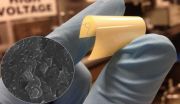

Easily manufactured, low cost, lightweight, flexible dielectric polymers that can operate at high temperatures may be the solution to energy storage and power conversion in electric vehicles and other high temperature applications, according to a team of Penn State engineers.

"Ceramics are usually the choice for energy storage dielectrics for high temperature applications, but they are heavy, weight is a consideration and they are often also brittle," said Qing Wang, professor of materials science and engineering, Penn State. "Polymers have a low working temperature and ...

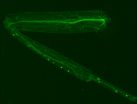

Researchers at USC have developed a yeast model to study a gene mutation that disrupts the duplication of DNA, causing massive damage to a cell's chromosomes, while somehow allowing the cell to continue dividing.

The result is a mess: Zombie cells that by all rights shouldn't be able to survive, let alone divide, with their chromosomes shattered and strung out between tiny micronuclei. Sometimes they're connected to each other by ultrafine DNA bridges. (Imagine tearing apart a hot pizza - these DNA bridges are like strings of cheese still draping between the separated ...

WASHINGTON - The Society for Public Health Education (SOPHE) announces the publication of a Health Education & Behavior theme section devoted to the latest research on domestic violence prevention and the effectiveness of community coalitions in 19 states to prevent and reduce intimate partner violence. The theme section "DELTA PREP" (Domestic Violence Prevention Enhancement and Leadership Through Alliances and Preparing and Raising Expectations for Prevention) presents findings from a multi-site project supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) ...

Abusive men put female partners at greater sexual risk, study finds

Abusive and controlling men are more likely to put their female partners at sexual risk, and the level of that risk escalates along with the abusive behavior, a UW study found.

Published in the Journal of Sex Research in July, the study looked at patterns of risky sexual behavior among heterosexual men aged 18 to 25, including some who self-reported using abusive and/or controlling behaviors in their relationships and others who didn't.

The research found that men who were physically and sexually ...

A critical immune organ called the thymus shrinks rapidly with age, putting older individuals at greater risk for life-threatening infections. A study published August 6 in Cell Reports reveals that thymus atrophy may stem from a decline in its ability to protect against DNA damage from free radicals. The damage accelerates metabolic dysfunction in the organ, progressively reducing its production of pathogen-fighting T cells.

The findings suggest that common dietary antioxidants may slow thymus atrophy and could represent a promising treatment strategy for protecting ...

CINCINNATI - Researchers have developed a new technology that precisely marks where groups of regulatory proteins called transcription factors bind DNA in the nuclei of live cells.

Reporting their data Aug. 6 in the journal Molecular Cell, scientists at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center say the new technology - called SpDamID - could allow scientists to answer basic questions about tissue development and disease that existing technology cannot address.

"With further development this technology has the potential to give investigators glimpses into biological ...

AUSTIN, Texas -- Men's and women's ideas of the perfect mate differ significantly due to evolutionary pressures, according to a cross-cultural study on multiple mate preferences by psychologists at The University of Texas at Austin.

The study of 4,764 men and 5,389 women in 33 countries and 37 cultures showed that sex differences in mate preferences are much larger than previously appreciated and stable across cultures.

"Many want to believe that women and men are identical in their underlying psychology, but the genders differ strikingly in their evolved mate preferences ...

Understanding how and why we evolved such large brains is one of the most puzzling issues in the study of human evolution. It is widely accepted that brain size increase is partly linked to changes in diet over the last 3 million years, and increases in meat consumption and the development of cooking have received particular attention from the scientific community. In a new study published in The Quarterly Review of Biology, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/682587, Dr. Karen Hardy and her team bring together archaeological, anthropological, genetic, physiological and ...

Researchers at the Babraham Institute and University of Massachusetts Medical School in the United States have developed a new model to study motor neuron degeneration and have used this to identify three genes involved in the neurodegeneration process. These findings could have relevance for understanding the progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and other forms of motor neuron disease (MND). ALS is the most common form of adult-onset motor neuron disease and kills over 1,200 people a year in the UK.

The researchers developed a new model to study neurodegeneration ...

Greenhouse gasses (GHG) emission savings due to final renewable energy consumption in electricity, cooling/heating and transport sectors rose at a compound annual growth rate of 8.8% from 2009 to 2012, confirming the renewables' great potential in climate change mitigation, according to a new JRC report. Nearly two thirds of the total savings came thanks to renewable energy development in Germany, Sweden, France, Italy and Spain.

The report assesses data on the use of renewable energy, submitted by EU Member States every two years, as required by EU legislation on renewable ...