(Press-News.org) This news release is available in Japanese.

There are no magic bullets for global energy needs. But fuel cells in which electrical energy is harnessed directly from live, self-sustaining chemical reactions promise cheaper alternatives to fossil fuels.

To facilitate faster energy conversion in these cells, scientists disperse nanoparticles made from special metals called 'noble' metals, for example gold, silver and platinum along the surface of an electrode. These metals are not as chemically responsive as other metals at the macroscale but their atoms become more responsive at the nanoscale. Nanoparticles made from these metals act as a catalyst, enhancing the rate of the necessary chemical reaction that liberates electrons from the fuel. While the nanoparticles are being sputtered onto the electrode they squash together like putty, forming larger clusters. This compacting tendency, called sintering, reduces the overall surface area available to molecules of the fuel to interact with the catalytic nanoparticles, thus preventing them from realizing their full potential in these fuel cells.

Research by the Nanoparticles by Design Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST), in collaboration with the SLAC National Laboratory in the USA and the Austrian Centre for Electron Microscopy and Nanoanalysis, has developed a way to prevent noble metal nanoparticles from compacting, by encapsulating them individually inside a porous shell made of a metal oxide. The OIST researchers published their findings in Nanoscale. Their work has immediate applications in the field of nano-catalysis for the manufacturing of more efficient fuel cells.

The OIST researchers designed a novel system. They encapsulated Palladium nanoparticles in a shell of Magnesium oxide. Then they dispersed this core-shell combination on an electrode and measured the immersed electrode's abilities in improving the rate of the electrochemical reaction that occurs in methanol fuel cells. They demonstrated that encapsulated Palladium nanoparticles give a significantly superior performance than bare Palladium nanoparticles.

The OIST researchers had previously realized that Magnesium oxide nanoparticles could form porous shells around noble metal nanoparticles while studying Magnesium and Palladium nanoparticles separately. The porosity of this added armor ensures it does not screen molecules of the fuel from reaching the encapsulated Palladium. Electron microscopy images confirmed that the Magnesium oxide shell simply acts as a spacer between the Palladium cores as they try to stick to each other, letting each to realize its full reactive potential.

The advanced nanoparticle deposition system at OIST allowed the researchers to fine tune the experimental parameters and vary the thickness of the encapsulating shell as well as the number of Palladium nanoparticles in the core with relative ease. Tuning sizes and structures of nanoparticles alters their physical and chemical properties for different applications.

"More core-shell combinations can be tried using our technique, with metals cheaper than Palladium for instance, like Nickel or Iron. Our results show enough promise to continue in this new direction," said Vidyadhar Singh, the paper's first author, and postdoctoral fellow under the supervision of Prof. Mukhles Sowwan, the director of OIST's Nanoparticles by Design Unit, who was also a corresponding author of the paper.

INFORMATION:

Scientists searched the chromosomes of more than 4,000 Huntington's disease patients and found that DNA repair genes may determine when the neurological symptoms begin. Partially funded by the National Institutes of Health, the results may provide a guide for discovering new treatments for Huntington's disease and a roadmap for studying other neurological disorders.

"Our hope is to find ways that we can slow or delay the onset of Huntington's devastating symptoms," said James Gusella, Ph.D., director of the Center for Human Genetic Research at Massachusetts General ...

Scientists on the NOvA experiment saw their first evidence of oscillating neutrinos, confirming that the extraordinary detector built for the project not only functions as planned but is also making great progress toward its goal of a major leap in our understanding of these ghostly particles.

NOvA is on a quest to learn more about the abundant yet mysterious particles called neutrinos, which flit through ordinary matter as though it weren't there. The first NOvA results, released this week at the American Physical Society's Division of Particles and Fields conference ...

WORCESTER, MA -- Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Medical School have found that Google Glass, a head-mounted streaming audio/video device, may be used to effectively extend bed-side toxicology consults to distant health care facilities such as community and rural hospitals to diagnose and manage poisoned patients. Published in the Journal of Medical Toxicology, the study also showed preliminary data that suggests the hands-free device helps physicians in diagnosing specific poisonings and can enhance patient care.

"In the present era of value-based care, ...

Health care organizations have been implementing health information technology at increasing rates in an effort to engage patients and caregivers improve patient satisfaction, and favorably impact outcomes. A new study led by researchers at Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) finds that a novel web-based, patient-centered toolkit (PCTK) used by patients and/or their healthcare proxys in the hospital setting helped them to engage in understanding and developing their plan of care, and has the potential to improve communication with providers. The results of the study are ...

Australian scientists have discovered many tropical, mountaintop plants won't survive global warming, even under the best-case climate scenario.

James Cook University and Australian Tropical Herbarium researchers say their climate change modelling of mountaintop plants in the tropics has produced an "alarming" finding.

They found many of the species they studied will likely not be able to survive in their current locations past 2080 as their high-altitude climate changes.

The Wet Tropics World Heritage Area in Queensland, Australia is predicted to almost completely ...

A James Cook University study shows fish retreating to deeper water to escape the heat, a finding that throws light on what to expect if predictions of ocean warming come to pass.

JCU scientists tagged 60 redthroat emperor fish at Heron Island in the southern Great Barrier Reef. The fish were equipped with transmitters that identified them individually and signaled their depth to an array of receivers around the island.

The experiment monitored fish for up to a year and found the fish were less likely to be found on the reef slope on warmer days. Scientists think ...

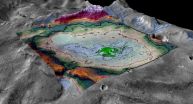

Mars turned cold and dry long ago, but researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder have discovered evidence of an ancient lake that likely represents some of the last potentially habitable surface water ever to exist on the Red Planet.

The study, published Thursday in the journal Geology, examined an 18-square-mile chloride salt deposit (roughly the size of the city of Boulder) in the planet's Meridiani region near the Mars Opportunity rover's landing site. As seen on Earth in locations such as Utah's Bonneville Salt Flats, large-scale salt deposits are considered ...

Ruxolitinib (trade name: Jakavi) has been approved since March 2015 for the treatment of adults with polycythaemia vera, a rare disease of the bone marrow. It can be used when the drug hydroxyurea is ineffective or not tolerated. The German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) examined in a dossier assessment whether this drug offers an added benefit over the appropriate comparator therapy.

According to the findings, ruxolitinib offers better relief of individual symptoms and improves quality of life. Dyspnoea and muscle cramps are more frequent, ...

Brussels, [7 August 2015] - An unresolved inflammatory response is likely to be involved from the early stages of disease development. Controlling inflammation is crucial to human health and a key future preventative and therapeutic target. In a recent ILSI Europe's article published in the British Journal of Nutrition, a coalition of experts explain how nutrition influences inflammatory processes and help reduce chronic diseases risk.

Inflammation is a normal component of host defence, but elevated unresolved chronic inflammation is a core perturbation in a range of ...

Simon Fraser University scientist Jonathan Moore has authored new research suggesting that a proposed controversial terminal to load fossil fuels in the Skeena River estuary has more far-reaching risks than previously recognized.

In a letter newly published in the journal Science Moore and First Nations leaders and fisheries biologists from throughout the Skeena watershed refer to the new data, which is on the Moore Lab site.

Moore is a Faculty of Science and a Faculty of Environment professor of ecology and conservation of freshwaters and the Liber Ero Chair of Coastal ...