(Press-News.org) Capture and convert--this is the motto of carbon dioxide reduction, a process that stops the greenhouse gas before it escapes from chimneys and power plants into the atmosphere and instead turns it into a useful product.

One possible end product is methanol, a liquid fuel and the focus of a recent study conducted at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory. The chemical reactions that make methanol from carbon dioxide rely on a catalyst to speed up the conversion, and Argonne scientists identified a new material that could fill this role. With its unique structure, this catalyst can capture and convert carbon dioxide in a way that ultimately saves energy.

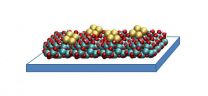

They call it a copper tetramer.

It consists of small clusters of four copper atoms each, supported on a thin film of aluminum oxide. These catalysts work by binding to carbon dioxide molecules, orienting them in a way that is ideal for chemical reactions. The structure of the copper tetramer is such that most of its binding sites are open, which means it can attach more strongly to carbon dioxide and can better accelerate the conversion.

The current industrial process to reduce carbon dioxide to methanol uses a catalyst of copper, zinc oxide and aluminum oxide. A number of its binding sites are occupied merely in holding the compound together, which limits how many atoms can catch and hold carbon dioxide.

"With our catalyst, there is no inside," said Stefan Vajda, senior chemist at Argonne and the Institute for Molecular Engineering and co-author on the paper. "All four copper atoms are participating because with only a few of them in the cluster, they are all exposed and able to bind."

To compensate for a catalyst with fewer binding sites, the current method of reduction creates high-pressure conditions to facilitate stronger bonds with carbon dioxide molecules. But compressing gas into a high-pressure mixture takes a lot of energy.

The benefit of enhanced binding is that the new catalyst requires lower pressure and less energy to produce the same amount of methanol.

Carbon dioxide emissions are an ongoing environmental problem, and according to the authors, it's important that research identifies optimal ways to deal with the waste.

"We're interested in finding new catalytic reactions that will be more efficient than the current catalysts, especially in terms of saving energy," said Larry Curtiss, an Argonne Distinguished Fellow who co-authored this paper.

Copper tetramers could allow us to capture and convert carbon dioxide on a larger scale--reducing an environmental threat and creating a useful product like methanol that can be transported and burned for fuel.

Of course the catalyst still has a long journey ahead from the lab to industry.

Potential obstacles include instability and figuring out how to manufacture mass quantities. There's a chance that copper tetramers may decompose when put to use in an industrial setting, so ensuring long-term durability is a critical step for future research, Curtiss said. And while the scientists needed only nanograms of the material for this study, that number would have to be multiplied dramatically for industrial purposes.

Meanwhile, the researchers are interested in searching for other catalysts that might even outperform their copper tetramer.

These catalysts can be varied in size, composition and support material, which results in a list of more than 2,000 potential combinations, Vajda said.

But the scientists don't have to run thousands of different experiments, said Peter Zapol, an Argonne physicist and co-author of this paper. Instead, they will use advanced calculations to make predictions, and then test the catalysts that seem most promising.

"We haven't yet found a catalyst better than the copper tetramer, but we hope to," Vajda said. "With global warming becoming a bigger burden, it's pressing that we keep trying to turn carbon dioxide emissions back into something useful."

For this research, the team used the Center for Nanoscale Materials as well as beamline 12-ID-C of the Advanced Photon Source, both DOE Office of Science User Facilities.

Curtiss said the Advanced Photon Source allowed the scientists to observe ultralow loadings of their small clusters, down to a few nanograms, which was a critical piece of this investigation.

INFORMATION:

The study, "Carbon dioxide conversion to methanol over size-selected Cu4 clusters at low pressures," was published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society and was funded by the DOE's Office of Basic Energy Sciences. Co-authors also included researchers from the University of Freiburg and Yale University.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. For more, visit http://www.anl.gov.

The Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

For years chemotherapy has been one of most common methods of treating cancer, but it comes with the substantial drawback of effecting healthy cells in the same way that it effects cancerous cells. This means that a subject of chemotherapy can experience great pain and sickness as a side effect of the potentially lifesaving treatment. A solution to this problem is targeted therapy, or the use of drugs, which more specifically targets cancer cells while ignoring nearby healthy cells. Targeted therapy is dependent on drugs which are tailored to inhibited cancer cell growth, ...

A new test developed by UBC researchers allows physicians to measure the effects of gene silencing therapy in Huntington's disease and will support the first human clinical trial of a drug that targets the genetic cause of the disease.

The gene silencing therapy being tested by UBC researchers aims to reduce the levels of a toxic protein in the brain that causes Huntington's disease.

The test was developed by Amber Southwell, Michael Hayden, and Blair Leavitt of UBC's Centre for Molecular Medicine and Therapeutics and the Centre for Huntington Disease in collaboration ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

There are no magic bullets for global energy needs. But fuel cells in which electrical energy is harnessed directly from live, self-sustaining chemical reactions promise cheaper alternatives to fossil fuels.

To facilitate faster energy conversion in these cells, scientists disperse nanoparticles made from special metals called 'noble' metals, for example gold, silver and platinum along the surface of an electrode. These metals are not as chemically responsive as other metals at the macroscale but their atoms become more ...

Scientists searched the chromosomes of more than 4,000 Huntington's disease patients and found that DNA repair genes may determine when the neurological symptoms begin. Partially funded by the National Institutes of Health, the results may provide a guide for discovering new treatments for Huntington's disease and a roadmap for studying other neurological disorders.

"Our hope is to find ways that we can slow or delay the onset of Huntington's devastating symptoms," said James Gusella, Ph.D., director of the Center for Human Genetic Research at Massachusetts General ...

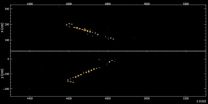

Scientists on the NOvA experiment saw their first evidence of oscillating neutrinos, confirming that the extraordinary detector built for the project not only functions as planned but is also making great progress toward its goal of a major leap in our understanding of these ghostly particles.

NOvA is on a quest to learn more about the abundant yet mysterious particles called neutrinos, which flit through ordinary matter as though it weren't there. The first NOvA results, released this week at the American Physical Society's Division of Particles and Fields conference ...

WORCESTER, MA -- Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Medical School have found that Google Glass, a head-mounted streaming audio/video device, may be used to effectively extend bed-side toxicology consults to distant health care facilities such as community and rural hospitals to diagnose and manage poisoned patients. Published in the Journal of Medical Toxicology, the study also showed preliminary data that suggests the hands-free device helps physicians in diagnosing specific poisonings and can enhance patient care.

"In the present era of value-based care, ...

Health care organizations have been implementing health information technology at increasing rates in an effort to engage patients and caregivers improve patient satisfaction, and favorably impact outcomes. A new study led by researchers at Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) finds that a novel web-based, patient-centered toolkit (PCTK) used by patients and/or their healthcare proxys in the hospital setting helped them to engage in understanding and developing their plan of care, and has the potential to improve communication with providers. The results of the study are ...

Australian scientists have discovered many tropical, mountaintop plants won't survive global warming, even under the best-case climate scenario.

James Cook University and Australian Tropical Herbarium researchers say their climate change modelling of mountaintop plants in the tropics has produced an "alarming" finding.

They found many of the species they studied will likely not be able to survive in their current locations past 2080 as their high-altitude climate changes.

The Wet Tropics World Heritage Area in Queensland, Australia is predicted to almost completely ...

A James Cook University study shows fish retreating to deeper water to escape the heat, a finding that throws light on what to expect if predictions of ocean warming come to pass.

JCU scientists tagged 60 redthroat emperor fish at Heron Island in the southern Great Barrier Reef. The fish were equipped with transmitters that identified them individually and signaled their depth to an array of receivers around the island.

The experiment monitored fish for up to a year and found the fish were less likely to be found on the reef slope on warmer days. Scientists think ...

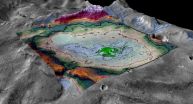

Mars turned cold and dry long ago, but researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder have discovered evidence of an ancient lake that likely represents some of the last potentially habitable surface water ever to exist on the Red Planet.

The study, published Thursday in the journal Geology, examined an 18-square-mile chloride salt deposit (roughly the size of the city of Boulder) in the planet's Meridiani region near the Mars Opportunity rover's landing site. As seen on Earth in locations such as Utah's Bonneville Salt Flats, large-scale salt deposits are considered ...