(Press-News.org) It's bacteria against bacteria, and one of them is going down.

Two UC Santa Barbara graduate students have demonstrated how certain microbes exploit proteins in nearby bacteria to deliver toxins and kill them. The mechanisms behind this bacterial warfare, the researchers suggest, could be harnessed to target pathogenic bacteria. Their findings appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

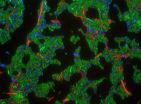

Lead authors Julia L.E. Willett and Grant C. Gucinski have detailed how gram-negative bacteria use contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI) systems to infiltrate and deliver protein toxins into neighboring cells. By studying the bacteria Escherichia coli (E. coli), they were able to document how CDI "translocation domains" can use multiple pathways to transfer those toxins into a cell. By understanding that mechanism, Willett said, it could be possible to use it as a model for pinpoint targeting of bacteria.

"The long-term, real-world potential is that if we know bacteria can deliver their own proteins into other cells, we might be able to use this as a delivery system for antibiotics and other therapeutics," said Willett, a doctoral student in UCSB's Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology (MCDB). She and Gucinski conducted the work under the direction of faculty adviser and MCDB professor Chris Hayes. Hayes is the second author on the paper.

"If we know the detailed mechanisms of delivery maybe we can target specific groups of bacteria," Willett continued. "Instead of taking an antibiotic that targets all bacteria, we might be able to deliver one that could specifically target one group of bad bacteria that leaves the good bacteria in your gut alone."

Gucinski, a graduate student researcher in UCSB's Biomolecular Science and Engineering Program, began studying E. coli as an undergraduate. Although it has a reputation as a nasty pathogen, that group of bacteria is generic enough to make an ideal research subject.

"E. coli is the easiest system to work with and very representative of the majority of other bacteria," Gucinski said. "The kind of CDI systems that we study are also found in a lot of different kinds of bacteria. This is the tip of the iceberg in our understanding of what we'll find in other CDI systems in other bacteria."

CDI were first described by David Low, professor of MCDB, in 2005. Low, a co-author of the current PNAS paper, reported how a bacterial cell would touch a neighboring cell -- one that was competing for resources in the environment -- and inject it with a toxin. Willett and Gucinski's research builds on Low's work by identifying the multiple ways CDI toxins exploit target cells. The key was in understanding the genetics of those targeted bacteria.

"We know that the cells would have these CDI systems; we know the genetics that are required to make this toxin system, but we were interested in the genetics on the other side, the genetics that are required in the cell that's being inhibited or the cell that's receiving this toxin," Willett explained. "What specifically in that cell is required for the toxin to go from outside the cell to inside the cell?"

Willett and Gucinski found that mutations in the target cells allowed CDI to exploit those cells and inject them with toxins.

"What these CDI systems have done is they've actually hijacked machinery that the cells already have," Willett said. "And so cells when they're growing need to take in nutrients, and the CDI systems hijack those pre-existing systems to deliver these toxins. It's not really tricking the target cells, but it's basically hijacking what's already there for the inhibitor cell's own benefit."

Looking ahead, Willett and Gucinski say potential therapeutic applications are tantalizing but years away. "We're still trying to understand the routes that we can get different CDI toxins into the cell," Gucinski said. "One interesting direction would be what other cargo we can deliver with E. coli, how we can manipulate and control the system to target the pathogens."

Given the rise of drug-resistant bacteria and a dearth of research into new antibiotics, Willett and Gucinski's research has the potential to open a new front in the fight against pathogenic bacteria.

"We hear on the news that a lot of pathogens are becoming resistant or people can no longer take certain antibiotics," Willett said. "And so this might be a new way to get around that. Instead of treating everything on a broad spectrum, if we could learn how a natural antibacterial system delivers things that kill other bacteria we might be able to more learn how we can deliver things like specific proteins or specific antibiotics to kill other bacteria."

INFORMATION:

Also contributing to the research was UCSB undergraduate Jackson P. Fatheree. The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship.

Some children react more strongly to negative experiences than others. Researchers from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) have found a link between aggression and variants of a particular gene.

But children who react most aggressively also tend to respond more strongly to good experiences, the Norwegian researchers found. These children's mood swings have deeper valleys, but also greater peaks.

Aggression is common in young children. Aggressive behaviour increases until children are around 4 years old, and then gradually subsides.

Research ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- A study provides multiple lines of new evidence that pigments and the microbodies that produce them can remain evident in a dinosaur fossil. In the journal Scientific Reports, an international team of paleontologists correlates the distinct chemical signature of animal pigment with physical evidence of melanosome organelles in the fossilized feathers of Anchiornis huxleyi, a bird-like dinosaur that died about 150 million years ago in China.

The idea that melanosomes, which produce melanin pigment, are preserved in fossils has been ...

Physicists have found a radical new way confine electromagnetic energy without it leaking away, akin to throwing a pebble into a pond with no splash.

The theory could have broad ranging applications from explaining dark matter to combating energy losses in future technologies.

However, it appears to contradict a fundamental tenet of electrodynamics, that accelerated charges create electromagnetic radiation, said lead researcher Dr Andrey Miroshnichenko from The Australian National University (ANU).

"This problem has puzzled many people. It took us a year to get this ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Many clinical trials use genome sequencing to learn which gene mutations are present in a patient's tumor cells. The question is important because targeting the right mutations with the right drugs can stop cancer in its tracks. But it can be difficult to determine whether there is evidence in the medical literature that particular mutations might drive cancer growth and could be targeted by therapy, and which mutations are of no consequence.

To help molecular pathologists, laboratory directors, bioinformaticians and oncologists identify key mutations ...

A study by the University of Liverpool has found that the genetic diversity of wild plant species could be altered rapidly by anthropogenic climate change.

Scientists studied the genetic responses of different wild plant species, located in a natural grassland ecosystem near Buxton, to a variety of simulated climate change treatments--including drought, watering, and warming--over a 15-year period.

Analysis of DNA markers in the plants revealed that the climate change treatments had altered the genetic composition of the plant populations. The results also indicated a ...

Twitter offers a public platform for people to post and share all sorts of content, from the serious to the ridiculous. While people tend to share political information with those who have similar ideological preferences, new research from NYU's Social Media and Political Participation Lab demonstrates that Twitter is more than just an "echo chamber."

The research is published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"Platforms like Twitter or Facebook are creating unprecedented opportunities for citizens to communicate with ...

Philadelphia, PA, August 27, 2015 - About 3% of colorectal cancers are due to Lynch syndrome, an inherited cancer susceptibility syndrome that predisposes individuals to various cancers. Close blood relatives of patients with Lynch syndrome have a 50% chance of inheritance. The role that PMS2 genetic mutations play in Lynch syndrome has been underestimated in part due to technological limitations. A new study in the Journal of Molecular Diagnostics describes a multi-method strategy to overcome existing technological limitations by more accurately identifying PMS2 gene mutations, ...

Needham, MA.-JBJS Case Connector, an online case report journal published by The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, has issued a "Watch" regarding relatively rare but potentially catastrophic complications from failure of modular head-neck prostheses commonly used in hip-replacement surgery.

The arthroplasty community currently feels that the advantages gained from modularity in hip implants outweigh the risks, but this Watch raises that risk-benefit question again. The decision to issue the Watch was prompted by a case report by Swann et al. in the August 26, 2015 JBJS ...

Analysis of blood samples from more than 5,000 people suggests that a more sensitive version of a blood test long used to verify heart muscle damage from heart attacks could also identify people on their way to developing hypertension well before the so-called silent killer shows up on a blood pressure machine.

Results of the federally funded study, led by Johns Hopkins investigators, found that people with subtle elevations in cardiac troponin T -- at levels well below the ranges detectable on the standard version of this "heart attack" test -- were more likely to be ...

Dogs get cancer, too. And they have even fewer treatment options than their human owners do. But an article in Chemical & Engineering News (C&EN), the weekly newsmagazine of the American Chemical Society, offers a glimmer of hope. It explores how clinical trials on man's best friend could be a win-win for both dogs and people.

Judith Lavelle, an intern at C&EN, notes that only a small percentage of potential human cancer drugs get approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Many of them fail when tested in people in clinical trials. A major reason for this late ...