(Press-News.org) Scientists believe that about 4 billion years ago, during a period called the Late Heavy Bombardment, the moon took a severe beating, as an army of asteroids pelted its surface, carving out craters and opening deep fissures in its crust. Such sustained impacts increased the moon's porosity, opening up a network of large seams beneath the lunar surface.

Now scientists at MIT and elsewhere have identified regions on the far side of the moon, called the lunar highlands, that may have been so heavily bombarded -- particularly by small asteroids -- that the impacts completely shattered the upper crust, leaving these regions essentially as fractured and porous as they could be. The scientists found that further impacts to these highly porous regions may have then had the opposite effect, sealing up cracks and decreasing porosity.

The researchers observed this effect in the upper layer of the crust -- a layer that scientists refer to as the megaregolith. This layer is dominated by relatively small craters, measuring 30 kilometers or less in diameter. In contrast, it appears that deeper layers of crust, that are affected by larger craters, are not quite as battered, and are less fractured and porous.

Jason Soderblom, a research scientist in MIT's Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, says the evolution of the moon's porosity can give scientists clues to some of the earliest life-supporting processes taking place in the solar system.

"The whole process of generating pore space within planetary crusts is critically important in understanding how water gets into the subsurface," Soderblom says. "On Earth, we believe that life may have evolved somewhat in the subsurface, and this is a primary mechanism to create subsurface pockets and void spaces, and really drives a lot of the rates at which these processes happen. The moon is a really ideal place to study this."

Soderblom and his colleagues, including Maria Zuber, the E.A. Griswold Professor of Geophysics and MIT's vice president for research, have published their findings in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Changing porosity

The team used data obtained by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) -- twin spacecraft that orbited the moon throughout 2012, each measuring the push and pull of the other as an indicator of the moon's gravity.

With the GRAIL data, researchers mapped the gravity field in and around more than 1,200 craters on the far side of the moon. This region, the lunar highlands, makes up the moon's most ancient, heavily cratered terrain.

They then carried out an analysis called a Bouger correction to subtract the gravitational effect of mountains, valleys, and other topology from the total gravity field. What's left is the gravity field beneath the surface, within the moon's crust.

"There's an assumption we do have to make, which is that there's no changes in the material itself, and that all of the bumps we're seeing [in the gravity field] are from changes in the porosity and the amount of air between the rock," Soderblom explains.

Soderblom calculated the gravity signatures in and around 1,200 craters on the far side of the moon, and compared the gravity within each crater with the gravity of the surrounding terrain, to determine whether an impact increased or decreased the local porosity.

Origin story

For craters smaller than 30 kilometers in diameter, he found impacts both increased and decreased porosity in the upper layer of the moon's crust.

"For the smallest craters that we're looking at, we think we're starting to see where the moon has gone through so much fracturing that it gets to a point where the porosity of the crust just stays at some constant level," Soderblom says. "You can keep impacting it and you'll hit regions where you'll increase porosity here and decrease it there, but on average it stays constant."

The researchers found that larger craters, which excavated much deeper into the moon's crust, only increased porosity in the underlying crust -- an indication that these deeper layers have not reached a steady state in porosity, and are not as fractured as the megaregolith.

Soderblom says the gravity signatures of the larger craters in particular may provide insight into just how many impacts the moon, and other terrestrial bodies, sustained during the Late Heavy Bombardment.

"For the smaller craters, it's like if you're filling a bucket, eventually your bucket gets full, but if you keep pouring cups of water into the bucket, you can't tell how many cups of water beyond full you've gone," Soderblom says. "Looking at the larger craters at the subsurface might give us insight, because that 'bucket' isn't full yet."

Ultimately, tracing the moon's changing porosity may help scientists track the trajectory of the moon's impactors 4 billion years ago.

"What we really hope to do is to figure out the number of impacts in the range of 100 kilometers in diameter, and from that, we can extrapolate to the smaller craters, assuming different populations of impactors, and those different assumptions will tell us where the impactors came from," Soderblom says. "This will help to understand the origin of the Late Heavy Bombardment, and whether it was disrupted material from the asteroid belt, or if it was further out."

INFORMATION:

This research was funded by NASA.

Additional background

ARCHIVE:

A twist on planetary origins

ARCHIVE:

Solving the mystery of the 'man on the moon'

ARCHIVE:

The moon's face doesn't tell its whole story

Researchers from Northwestern University and Yale University have developed a user-friendly technology to help scientists understand how proteins work and fix them when they are broken. Such knowledge could pave the way for new drugs for a myriad of diseases, including cancer.

The human body has a nifty way of turning its proteins on and off to alter their function and activity in cells: phosphorylation, the reversible attachment of phosphate groups to proteins. These "decorations" on proteins provide an enormous variety of function and are essential to all forms of life. ...

Alexandria, VA - In a study covered by EARTH Magazine, geoscientists identified fossils that are helping close the 15-million-year period in the fossil record known as Romer's Gap - the time from when fish showed early evidence of arms and legs until we definitively see four-legged land animals.

Scientists have been wondering for decades whether Romer's Gap exists because tetrapod fossils from that time were not preserved, or because their fossils simply have not been discovered yet. These new fossils are starting to close the gap and change the way scientists interpret ...

IVF cycles using embryos that have been frozen and thawed are just as successful as fresh embryos according to a new UNSW report.

The Assisted Reproductive Technology in Australia and New Zealand 2013 report, by UNSW's National Perinatal Epidemiology and Statistics Unit (NPESU), shows in the five years to 2013, fresh embryo IVF cycles that resulted in a baby remained stable at around 23%.

However, there has been a more than 25% increase in the birth rate for frozen embryo transfers in the last five years, rising from 18% to 23%.

The report also found a growing number ...

Patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (sinus infection) and obstructive sleep apnea report a poor quality of life, which is substantially improved following endoscopic sinus surgery, according to a study published online by JAMA Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery.

A growing body of literature has highlighted the important links between quality of life (QOL), sleep, and chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), such that disease severity has been correlated with worse QOL and patients with worse QOL have poor sleep. It is possible that CRS propagates sleep dysfunction through many ...

This news release is available in German.

The goal of brain simulations using supercomputers is to understand the processes in our brain. This is a mammoth task: the activity of an estimated 100 billion nerve cells - also known as neurons - must be represented . It is also a task that has historically been impossible because even the most powerful computers in the world can only simulate one percent of the nerve cells due to memory constraints. For this reason, scientists have turned to downscaled models. However, this downscaling is problematic, as shown by a recent ...

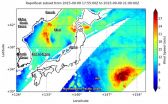

Japan has experienced large rainfall that caused flooding and large evacuations as a result of two weather systems. NASA's GPM Core satellite measured rainfall as NASA's RapidScat saw Etau and Typhoon Kilo on either side of Japan.

Over the past week Japan has experienced extreme rainfall that resulted in flooding, landslides and many injuries. A nearly stationary front that was already moving over Japan caused much of the rain but Tropical Storm Etau also interacted with the front and magnified the scale of the deluge.

Heavy rainfall led to the evacuation of over one ...

NEW YORK, NY (September 10, 2015)--Researchers have discovered why long-term use of L-DOPA (levodopa), the most effective treatment for Parkinson's disease, commonly leads to a movement problem called dyskinesia, a side effect that can be as debilitating as Parkinson's disease itself.

Using a new method for manipulating neurons in a mouse model of Parkinson's, a Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) research team found that dyskinesia arises when striatonigral neurons become less responsive to GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter. This suggests that it may be possible ...

Alexandria, VA - The American Geosciences Institute's (AGI) is pleased to announce the release of a community consensus statement on access and inclusion of geoscientists with disabilities. This statement was inspired by the 2014 AGI Leadership Forum, which brought together the Executive Directors and Presidents of AGI's Member Societies to discuss the issue of access and inclusion of persons with disabilities in the geosciences.

The meeting was facilitated by the Executive Director of the International Association for Geoscience Diversity (IAGD) Christopher Atchison, ...

NASA's RapidScat instrument analyzed the sustained surface winds of Tropical Storm Henri on Sept. 8 as the storm was intensifying.

When the International Space Station flew over Tropical Depression 8 in the Eastern Atlantic Ocean on September 8 at 1p.m. EDT, NASA's RapidScat instrument aboard captured data on the storm's surface winds. RapidScat showed that there were tropical-storm-force winds north and east of the center near 27 meters per second (60.4 mph/97.2 kph). However, sustained winds on the west and southwestern quadrants were near 12 meters per second (26.8 ...

September 10, 2015 (Washington) - There are substantial differences among Americans when it comes to knowledge and understanding of science topics, especially by educational levels as well as by gender, age, race and ethnicity, according to a new Pew Research Center report.

The representative survey of more than 3,200 U.S. adults finds that, on the 12 multiple-choice questions asked, Americans gave more correct than incorrect answers. The median was eight correct answers out of 12 (mean 7.9). Some 27% answered eight or nine questions correctly, while another 26% answered ...