(Press-News.org) What happens in the brain when our conscious awareness fades during general anesthesia and normal sleep? Finnish scientists studied this question with novel experimental designs and functional brain imaging. They succeeded in separating the specific changes related to consciousness from the more widespread overall effects, and discovered that the effects of anesthesia and sleep on brain activity were surprisingly similar. These novel findings point to a common central core brain network fundamental for human consciousness.

Explaining the biological basis of human consciousness is one of the greatest challenges of science. While the loss and return of consciousness, as regulated by drugs or physiological sleep, have been employed as model systems in the study of human consciousness, previous research results have been confounded by many experimental simplifications.

"One major challenge has been to design a set-up, where brain data in different states differ only in respect to consciousness. Our study overcomes many previous confounders, and for the first time, reveals the neural mechanisms underlying connected consciousness," says Harry Scheinin, Docent of Pharmacology, Anesthesiologist, and the Principal Investigator of the study from the University of Turku, Finland.

A new and innovative experimental set-up

Brain activity was measured with positron emission tomography (PET) imaging during different states of consciousness in two separate experiments in the same group of healthy subjects. Measurements were made during wakefulness, escalating and constant levels of two anesthetic agents, and during sleep-deprived wakefulness and Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) sleep.

In the first experiment, the subjects were randomly allocated to receive either propofol or dexmedetomidine (two anesthetic agents with different molecular mechanisms of action) at stepwise increments until the subjects no longer responded. In the sleep study, they were allowed to fall asleep naturally. In both experiments, the subjects were roused to achieve rapid recovery to a responsive state, followed by immediate and detailed interviews of subjective experiences from the preceding unresponsive period. Unresponsive anesthetic states and verified NREM sleep stages, where a subsequent report of mental content included no signs of awareness of the surrounding world, indicated a disconnected state in the study participants. Importantly, the drug dosing in the first experiment was not changed before or during the shift in the behavioral state of the subjects.

"This unique experimental design was the key idea of our study and enabled us to distinguish the changes that were specific to the state of consciousness from the overall effects of anesthesia," explains Annalotta Scheinin, Anesthesiologist, Doctoral Candidate and the first author of the paper.

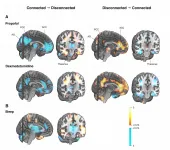

Researchers discovered a common central core brain network

When PET images of responsive and connected brains were compared with those of unresponsive and disconnected, the scientists found that activity of the thalamus, cingulate cortices and angular gyri were affected independently of the used anesthetic agent, drug concentration and direction of change in the state of consciousness (see figure). Strikingly analogous findings were obtained when physiological sleep was compared with sleep-deprived wakefulness. Brain activity changes were much more extensive when the disconnected states were compared with a fully awake state. State-specific findings were thus distinct and separable from the overall effects of drug-induced anesthesia and natural sleep, which included widespread suppression of brain activity across cortical areas.

These findings identify a central core brain network that is fundamental for human consciousness.

"General anesthesia seems to resemble normal sleep more than has traditionally been thought. This interpretation is, however, well in line with our recent electrophysiological findings in another anesthesia study," says Harry Scheinin.

Subjective experiences are common during general anesthesia

Interestingly, unresponsiveness rarely denoted unconsciousness (i.e., total absence of subjective experiences), as most participants reported internally generated experiences, such as dreams, in the interviews. This is not an entirely new finding as dreams are commonly reported by patients after general anesthesia.

"However, because of the minimal delay between the awakenings and the interviews, the current results add significantly to our understanding of the nature of the anesthetic state. Against a common belief, full loss of consciousness is not needed for successful general anesthesia, as it is sufficient to just disconnect the patient's experiences from what is going on in the operating room," explains Annalotta Scheinin.

The new study sheds light on the fundamental nature of human consciousness and brings new information on brain functions in intermediate states between wakefulness and complete unconsciousness. These findings may also challenge our current understanding of the essence of general anesthesia.

INFORMATION:

The experiments were carried out at Turku PET Centre as a joint effort of the research groups of Harry Scheinin studying anesthesia mechanisms, and Professor of Psychology Antti Revonsuo studying human consciousness and the brain from the point of view of philosophy and psychology, in collaboration with Professor Michael Alkire from the University of California, Irvine, USA. Turku PET Centre is a Finnish National Research Institute established by University of Turku, Åbo Akademi University and Turku University Hospital. The study was funded by the Academy of Finland and the Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation.

A fascinating substance with unique properties, ice has intrigued humans since time immemorial. Unlike most other materials, ice at very low temperature is not as ordered as it could be. A collaboration between the Scuola Internazionale Superiore di Studi Avanzati (SISSA), the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP), the Institute of Physics Rosario (IFIR-UNR), with the support of the Istituto Officina dei Materiali of the Italian National Research Council (CNR-IOM), made new theoretical inroads on the reasons why this happens and on the way in which some of the missing order can be recovered. In that ordered state the team ...

Small studies have suggested that a group of medications called RAS inhibitors may be harmful in persons with advanced chronic kidney disease, and physicians therefore often stop the treatment in such patients. Researchers at Karolinska Institutet now show that although stopping the treatment is linked to a lower risk of requiring dialysis, it is also linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular events and death. The results are published in The Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects approximately ten percent of the global population. Hypertension is ...

Scientific articles in the field of physics are mostly very short and deal with a very restricted topic. A remarkable exception to this is an article published recently by physicists from the Universities of Münster and Düsseldorf. The article is 127 pages long, cites a total of 1075 sources and deals with a wide range of branches of physics - from biophysics to quantum mechanics.

The article is a so-called review article and was written by physicists Michael te Vrugt and Prof. Raphael Wittkowski from the Institute of Theoretical Physics and the Center for Soft Nanoscience at the University of Münster, together with ...

Although plants are anchored to the ground, they spend most of their lifetime swinging in the wind. Like animals, plants have 'molecular switches' on the surface of their cells that transduce a mechanical signal into an electrical one in milliseconds. In animals, sound vibrations activate 'molecular switches' located in the ear. Scientists from the CNRS, INRAE, Ecole Polytechnique, Université Paris-Saclay and Université Clermont-Auvergne (1) have found that in plants, rapid oscillations of stems and leaves ...

How can cells adhere to surfaces and move on them? This is a question which was investigated by an international team of researchers headed by Prof. Michael Hippler from the University of Münster and Prof. Kaiyao Huang from the Institute of Hydrobiology (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan, China). The researchers used the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as their model organism. They manipulated the alga by altering the sugar modifications in proteins on the cell surface. As a result, they were able to alter the cellular surface adhesion, also known as adhesion force. The results have now been published in the ...

Thanks to the marine worm Platynereis dumerilii, an animal whose genes have evolved very slowly, scientists from CNRS, Université de Paris and Sorbonne Université, in association with others at the University of Saint Petersburg and the University of Rio de Janeiro, have shown that while haemoglobin appeared independently in several species, it actually descends from a single gene transmitted to all by their last common ancestor. These findings were published on 29 December 2020 in BMC Evolutionary Biology.

Having red blood is not peculiar to humans or mammals. ...

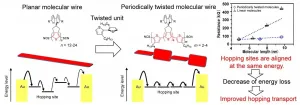

Osaka, Japan - Researchers at Osaka University synthesized twisted molecular wires just one molecule thick that can conduct electricity with less resistance compared with previous devices. This work may lead to carbon-based electronic devices that require fewer toxic materials or harsh processing methods.

Organic conductors, which are carbon-based materials that can conduct electricity, are an exciting new technology. Compared with conventional silicon electronics, organic conductors can be synthesized more easily, and can even be made into molecular wires. However, these structures suffer from reduced electrical conductivity, which prevents ...

After "COVID-19," the term that most people will remember best from 2020 is likely to be "social distancing." While it most commonly applied to social gatherings with family and friends, it has impacted the way many receive medical care. Historically, the United States has been relatively slow to broadly adopt telemedicine, largely emphasizing in-person visits.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in the spring of 2020, necessitated increased use of virtual or phone call visits, even prompting the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to relax some of its regulations, primarily for video-based ...

N-Aryl-C-nitroazoles are an important class of heterocyclic compounds. They are used as pesticides and fungicides. However, these substances could be toxic to humans and cause mutations. As they are not frequently used, there is little data about them in the medicinal chemistry literature. However, it has been suggested recently that the groups of compounds that are traditionally avoided can help to fight pathogenic bacteria. Yet, to reduce toxic effects, a great amount of work must be carried out at the molecular level, ...

The flag leaf is the last to emerge, indicating the transition from crop growth to grain production. Photosynthesis in this leaf provides the majority of the carbohydrates needed for grain filling--so it is the most important leaf for yield potential. A team from the University of Illinois and the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) found that some flag leaves of different varieties of rice transform light and carbon dioxide into carbohydrates better than others. This finding could potentially open new opportunities for breeding higher yielding rice varieties.

Published ...