The study appears in Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, published by Elsevier.

"The relationship between TBI and PTSD has garnered increased attention in recent years as studies have shown considerable overlap in risk factors and symptoms," said lead author Murray Stein, MD, MPH, FRCPC, a Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry and Family Medicine & Public Health at the University of California San Diego, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA. "In this study, we were able to use data from TRACK-TBI, a large longitudinal study of patients who present in the Emergency Department with TBIs serious enough to warrant CT (computed tomography) scans."

The researchers followed over 400 such TBI patients, assessing them for PTSD at 3 and 6 months after their brain injury. At 3 months, 77 participants, or 18 percent, had likely PTSD; at 6 months, 70 participants or 16 percent did. All subjects underwent brain imaging after injury.

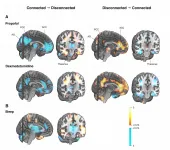

"MRI studies conducted within two weeks of injury were used to measure volumes of key structures in the brain thought to be involved in PTSD," said Dr. Stein. "We found that the volume of several of these structures were predictive of PTSD 3-months post-injury."

Specifically, smaller volume in brain regions called the cingulate cortex, the superior frontal cortex, and the insula predicted PTSD at 3 months. The regions are associated with arousal, attention and emotional regulation. The structural imaging did not predict PTSD at 6 months.

The findings are in line with previous studies showing smaller volume in several of these brain regions in people with PTSD and studies suggesting that the reduced cortical volume may be a risk factor for developing PTSD. Together, the findings suggest that a "brain reserve," or higher cortical volumes, may provide some resilience against PTSD.

Although the biomarker of brain volume differences is not yet robust enough to provide clinical guidance, Dr. Stein said, "it does pave the way for future studies to look even more closely at how these brain regions may contribute to (or protect against) mental health problems such as PTSD."

Cameron Carter, MD, Editor of Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, said of the work, "This very important study uses magnetic resonance imaging to take the field a step closer to understanding why some people develop PTSD after trauma and others do not. It also lays the groundwork for future research aimed at using brain imaging to help predict that a person is at increased risk and may benefit from targeted interventions to reduce the clinical impact of a traumatic event."

INFORMATION:

Notes for editors

The article is "Smaller Regional Brain Volumes Predict Posttraumatic Stress Disorder at 3 Months after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury," by Murray Stein, Esther Yuh, Sonia Jain, David Okonkwo, Christine Mac Donald, Harvey Levin, Joseph Giancino, Sureyya Dikmen, Mary Vassar, Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, Claudia Robertson, Lindsay Nelson, Michael McCrea, Xiaoying Sun, Nancy Temkin, Sabrina Taylor, Amy Markowtiz, Geoffrey Manley, Pratik Mukherjee, on behalf of the TRACK-TBI Investigators (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2020.10.008). It appears as an Article in Press in Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, published by Elsevier.

Copies of this paper are available to credentialed journalists upon request; please contact Rhiannon Bugno at BPCNNI@sobp.org or +1 254 522 9700. Journalists wishing to interview the authors may contact Murray B. Stein at mstein@health.ucsd.edu.

The authors' affiliations and disclosures of financial and conflicts of interests are available in the article.

Cameron S. Carter, MD, is Professor of Psychiatry and Psychology and Director of the Center for Neuroscience at the University of California, Davis. His disclosures of financial and conflicts of interests are available here.

About Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging

Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging is an official journal of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, whose purpose is to promote excellence in scientific research and education in fields that investigate the nature, causes, mechanisms and treatments of disorders of thought, emotion, or behavior. In accord with this mission, this peer-reviewed, rapid-publication, international journal focuses on studies using the tools and constructs of cognitive neuroscience, including the full range of non-invasive neuroimaging and human extra- and intracranial physiological recording methodologies. It publishes both basic and clinical studies, including those that incorporate genetic data, pharmacological challenges, and computational modeling approaches.

The 2019 Impact Factor score for Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging is 5.335.

http://www.sobp.org/bpcnni

About Elsevier

As a global leader in information and analytics, Elsevier helps researchers and healthcare professionals advance science and improve health outcomes for the benefit of society. We do this by facilitating insights and critical decision-making for customers across the global research and health ecosystems.

In everything we publish, we uphold the highest standards of quality and integrity. We bring that same rigor to our information analytics solutions for researchers, health professionals, institutions and funders.

Elsevier employs 8,100 people worldwide. We have supported the work of our research and health partners for more than 140 years. Growing from our roots in publishing, we offer knowledge and valuable analytics that help our users make breakthroughs and drive societal progress. Digital solutions such as ScienceDirect, Scopus, SciVal, ClinicalKey and Sherpath support strategic research management, R&D performance, clinical decision support, and health education. Researchers and healthcare professionals rely on our 2,500+ digitized journals, including The Lancet and Cell, our 40,000 e-book titles; and our iconic reference works, such as Gray's Anatomy. With the Elsevier Foundation and our external Inclusion & Diversity Advisory Board, we work in partnership with diverse stakeholders to advance inclusion and diversity in science, research and healthcare in developing countries and around the world.

Elsevier is part of RELX, a global provider of information-based analytics and decision tools for professional and business customers. http://www.elsevier.com

Media contact

Rhiannon Bugno,

Editorial Office

Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging

+1 254 522 9700

BPCNNI@sobp.org