Low genetic diversity in two manatee species off South America

Study raises the alarm for better conservation actions

2021-01-05

(Press-News.org) Worldwide, marine megafauna are at risk of extinction due to climate change, habitat loss, pollution, overhunting, population fragmentation, and hybridization with related species in areas disturbed by humans. Genetic studies can help determine the conservation status of marine animals, identifying threats to species conservation and informing interventions and policies, such as the protection of diversity hotspots or corridors for gene flow.

In a new study in Frontiers in Marine Science, researchers for the first time measured genetic diversity in manatees at a large geographical scale -- that is, along the northern coastline of South America. They show that the Antillean subspecies of the West Indian manatee forms a single, non-continuous population along the Brazilian coastline. Manatees from this population occasionally interbreed with the Antillean subspecies population located further North and West, between Guyana and Venezuela. Moreover, there seems to be no natural hybridization between the Antillean Amazonian manatee, even though their habitats overlap in the mouth of the Amazon river.

The Antillean subspecies of the West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus) and the Amazonian manatee (Trichechus inunguis) (order Sirenia) are both classified as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Antillean manatees occur across most of the Caribbean and along the Atlantic coast of Central and South America. In contrast, the Amazonian manatee is exclusively found in the mouth of the Amazon River. Historically, both were hunted intensively. Though hunting pressure has subsided, both remain at risk due to further anthropogenic threats, especially habitat degradation and collisions with boats. Manatees have strict habitat requirements, mainly places with seagrass and freshwater, such as estuaries. Due to continuous human pressure on their habitats, such as seagrass meadows, populations have decreased, potentially leading to a decrease in genetic variability.

''Genetic diversity is critical for species to be able to adapt to changing environments and avoid inbreeding and needs to be considered to allow for long-term protection of species,'' says coauthor Dr Margaret Hunter from the Wetland and Aquatic Research Center of the U.S. Geological Survey in Gainesville, Florida. "Here we show that manatee populations of Venezuela, Guyana and Brazil have some degree of interrelatedness but overall low genetic diversity.'"

To determine whether there is genetic connectivity between the West Indian and Amazonian manatee, the authors took 17 DNA samples from the Amazonian manatee, 78 from the Antillean subspecies in Brazil (southern cluster of populations) and 11 from Guyana and Venezuela (northern cluster), including adults and calves, and measured diversity at nuclear and mitochondrial neutral genetic markers.

The researchers found no evidence of natural hybridization between the two species. What they did find was evidence of gene flow between the northern and southern cluster of Antillean manatees. It seems the physical barrier of the Amazon River plume is not enough to block gene flow between the northern and southern cluster.

''These results make it possible for us to understand current genetic diversity of the Brazilian West Indian manatee population,'' says coauthor Dr Fábia de Oliveira Luna from Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation - National Center for Research and Aquatic Mammals Conservation, Brazil. ''We call on policymakers to improve the national action plan. An important action is the creation of new protected areas, which help establish biological corridors and promote gene flow. Another is to protect habitats where manatees give birth. Newborn calves have stranded along the Ceará and Rio Grande do Norte coastline of Brazil: upon rescue, these should released into the genetic population of origin, or in gap areas without residing manatees. In contrast, captive breeding should be avoided for now as enough calves are born in the wild."

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-05

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- A small portion of scientific papers are retracted for research that is in error or fraudulent. But those papers can continue to be cited by other scientists in their work, potentially passing along the misinformation from the retracted articles.

Jodi Schneider, a professor of information sciences at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who studies scholarly publications and how information gets used, is considering how scientific journals can better communicate about retracted articles. In a new study published in the ...

2021-01-05

Most of the mangrove forests on the coasts of Oman disappeared about 6,000 years ago. Until now, the reason for this was not entirely clear. A current study of the University of Bonn (Germany) now sheds light on this: It indicates that the collapse of coastal ecosystems was caused by climatic changes. In contrast, falling sea level or overuse by humans are not likely to be the reasons. The speed of the mangrove extinction was dramatic: Many of the stocks were irreversibly lost within a few decades. The results are published in the journal Quaternary Research.

Mangroves are trees that occupy a very special ecological niche: They grow in the so-called tidal range, meaning coastal areas that are ...

2021-01-05

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. -- If everything moved 40,000 times faster, you could eat a fresh tomato three minutes after planting a seed. You could fly from New York to L.A. in half a second. And you'd have waited in line at airport security for that flight for 30 milliseconds.

Thanks to machine learning, designing materials for new, advanced technologies could accelerate that much.

A research team at Sandia National Laboratories has successfully used machine learning -- computer algorithms that improve themselves by learning patterns in data -- to complete cumbersome materials science calculations more than 40,000 times faster than normal.

Their results, published Jan. 4 in END ...

2021-01-05

Australian research has identified a new mechanism in which prostate cancer cells can 'switch' character and become resistant to therapy.

These findings, just published in Cell Reports, are an important development in unravelling how an aggressive subtype of prostate cancer, neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC), develops after hormonal therapies.

It is well established that some tumours show increased cellular 'plasticity' in response to new or stressful conditions, such as cancer therapy, says lead researcher Associate Professor Luke Selth, from the Flinders ...

2021-01-05

What The Study Did: Data from public health surveillance of reported COVID-19 cases and seroprevalence surveys were used in this observational study that reports an estimated 46.9 million SARS-CoV-2 infections, 28.1 million symptomatic infections, 956,174 hospitalizations and 304,915 deaths occurred in the U.S. through November 15, 2020.

Authors: Frederick J. Angulo, D.V.M., Ph.D., of Medical Development and Scientific/Clinical Affairs of Pfizer Vaccines, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33706)

Editor's ...

2021-01-05

A new study led by researchers at the Universities of Bristol, Exeter, and Bath helps to shed light on the winter weather we may soon have in store following a dramatic meteorological event currently unfolding high above the North Pole.

Weather forecasting models are predicting with increasing confidence that a sudden stratospheric warming (SSW) event will take place today, 5 January 2021.

The stratosphere is the layer of the atmosphere from around 10-50km above the earth's surface. SSW events are some of the most extreme of atmospheric phenomena and can see polar stratospheric temperature increase by up to 50°C over the course of a few days. Such events ...

2021-01-05

By André Julião | Agência FAPESP - The black lion tamarin (Leontopithecus chrysopygus) once inhabited most forest areas in the state of São Paulo, Southeast Brazil, but currently occupies only some Atlantic Rainforest remnants there. In recent years, after various studies of the endangered species, environmental NGO Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas (IPÊ) moved groups of these animals to areas from which the species had disappeared.

Similar initiatives have now been reinforced by a group of researchers at IPÊ, São Paulo State University (UNESP) and the Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT), who cross-tabulated climate data and data on landscape (forest cover) to determine the sites best suited for future ...

2021-01-05

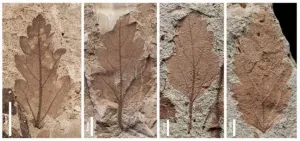

The asteroid impact 66 million years ago that ushered in a mass extinction and ended the dinosaurs also killed off many of the plants that they relied on for food. Fossil leaf assemblages from Patagonia, Argentina, suggest that vegetation in South America suffered great losses but rebounded quickly, according to an international team of researchers.

"Every mass extinction event is like a reset button, and what happens after that reset depends on which organisms survive and how they shape the biosphere," said Elena Stiles, a doctoral student at the University of Washington who completed the research as part of her master's thesis at Penn State. "All the biodiversity ...

2021-01-05

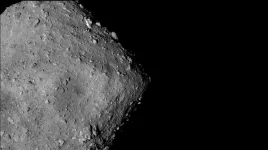

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Last month, Japan's Hayabusa2 mission brought home a cache of rocks collected from a near-Earth asteroid called Ryugu. While analysis of those returned samples is just getting underway, researchers are using data from the spacecraft's other instruments to reveal new details about the asteroid's past.

In a study published in Nature Astronomy, researchers offer an explanation for why Ryugu isn't quite as rich in water-bearing minerals as some other asteroids. The study suggests that the ancient parent body from which Ryugu was formed had likely dried out in some kind of heating event before Ryugu came into being, which left Ryugu itself drier than expected.

"One of the ...

2021-01-05

Repeated intravenous (IV) ketamine infusions significantly reduce symptom severity in individuals with chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and the improvement is rapid and maintained for several weeks afterwards, according to a study conducted by researchers from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The study, published September XX in the American Journal of Psychiatry, is the first randomized, controlled trial of repeated ketamine administration for chronic PTSD and suggests this may be a promising treatment for PTSD patients.

"Our findings provide insight into the treatment efficacy of repeated ketamine ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Low genetic diversity in two manatee species off South America

Study raises the alarm for better conservation actions