Intelligence deficit: Conclusion from the mouse to the human being

Researchers create an animal model for studying GPI anchor deficiencies

2021-01-07

(Press-News.org) Impaired intelligence, movement disorders and developmental delays are typical for a group of rare diseases that belong to GPI anchor deficiencies. Researchers from the University of Bonn and the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics used genetic engineering methods to create a mouse that mimics these patients very well. Studies in this animal model suggest that in GPI anchor deficiencies, a gene mutation impairs the transmission of stimuli at the synapses in the brain. This may explain the impairments associated with the disease. The results are now published in the journal "Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS)".

Just as ships anchor to the seabed in storms and waves, GPI anchors (GPI = glycosylphosphatidylinositol) ensure that special proteins can hold on to the outside of living cells. If the GPI anchor does not function properly due to a gene mutation, the signal transmission and transport between cells are disrupted. "GPI anchor deficiencies comprise a group of rare diseases that primarily cause intellectual deficits and developmental delays," explains Prof. Dr. Peter Krawitz from the Institute for Genomic Statistics and Bioinformatics at the University Hospital Bonn, who started his research at the Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin and continued it at the University Hospital Bonn. About 20 to 30 genes can be altered in GPI anchor deficiency.

A mutation in the PIGV gene was found in most European patients. It encodes an enzyme that is of great importance for the synthesis of the GPI anchor. Using the CRISPR-Cas9 gene scissors, the researchers and their colleagues from the Max-Planck-Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin modified the PIGV gene in mice based on a model of the patients. "Extensive behavioral tests have shown that this mouse model very closely reflects the disease observed in humans," says Miguel Rodríguez de los Santos from the Institute for Medical Genetics and Human Genetics at the Charité. He has been working with Prof. Krawitz for years and is now continuing his research at the University Hospital Bonn.

How similar is the mouse to human patients?

The behavioral tests on the genetically modified mice were carried out in cooperation with scientists from the "Animal Outcome Core Facility" of the NeuroCure Cluster of Excellence at the Charité. The animals exhibited cognitive deficits, just like the patients. For example, they showed significantly worse spatial orientation than mice without this mutation and displayed altered social behavior. "They were particularly sociable, which is something we did not expect," reports Rodríguez de los Santos.

Research revealed that patients with GPI anchor deficiencies also exhibit this sociability in some cases. The PIGV-altered mice also displayed deviations in the day-night rhythm. "This symptom has so far not appeared to be relevant, but it is certainly described in patients," says Krawitz. "We now have the rare case that the large similarity of a mouse model allows us to infer and re-evaluate the symptoms of patients in reverse."

Dysregulations in the hippocampus

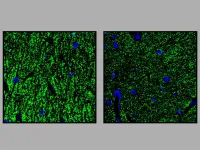

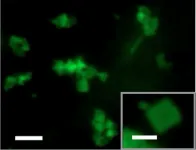

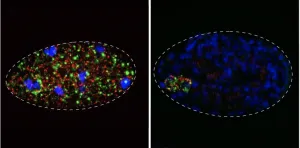

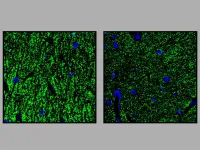

The researchers knew from preliminary studies that the hippocampus plays a major role in GPI anchor deficiencies. This brain structure, which resembles the shape of a seahorse, enables access to memories. The researchers studied microglia cells and subicular neurons from the hippocampus of genetically modified mice. Microglia cells are immune cells of the brain that fend off intruders. The subicular neurons are also responsible for memory retrieval. "Many genes in these two cell types were misregulated," says Rodríguez de los Santos. This could explain why the mice showed orientation problems in the tests.

Researchers at the Neuroscience Research Center of the Charité studied the electric fields in the hippocampus of genetically modified mice. "This showed that the transmission of stimuli at the synapses was impaired," says Krawitz. The results in the animal model suggest that the intellectual deficits found in the patients may be related to this synapse defect. Together with colleagues involved in translational epilepsy research at the University Hospital Bonn under Prof. Dr. Albert Becker, the researchers also discovered that the transgenic mice have an increased susceptibility to epilepsy. A further similarity with humans: Approximately 70 percent of patients with GPI anchor deficiencies develop epilepsy, again possibly caused by a synapse defect. Krawitz: "These observations and our mouse model open up completely new possibilities for further research in this direction."

INFORMATION:

Participating institutions

In addition to the University of Bonn, the study included the Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, the Berlin-Brandenburg School for Regenerative Therapies Berlin, the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics, the University of Zurich, the Humboldt University of Berlin, The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, Connecticut, University of Connecticut and the University Medical Center Göttingen.

Publication: Miguel Rodríguez de los Santos, Marion Rivalan, Friederike S. David, Alexander Stumpf, Julika Pitsch, Despina Tsortouktzidis, Laura Moreno Velasquez, Anne Voigt, Daniele Mattei, Melissa Long, Guido Vogt, Alexej Knaus, Björn Fischer-Zirnsak, Lars Wittler, Bernd Timmermann, Peter N. Robinson, Denise Horn, Stefan Mundlos, Uwe Kornak, Albert J. Becker, Dietmar Schmitz, York Winter, Peter M. Krawitz: A CRISPR-Cas9-engineered mouse model for GPI anchor deficiency mirrors human phenotype and exhibits hippocampal synaptic dysfunctions, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2014481118

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-07

INDIANAPOLIS-- Researchers at the Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center published promising findings today in the New England Journal of Medicine on preventing a common complication to lifesaving blood stem cell transplantation in leukemia.

Sherif Farag, MD, PhD, found that using a drug approved for Type 2 diabetes reduces the risk of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), one of the most serious complications of blood stem cell transplantation. GVHD occurs in more than 30 percent of patients and can lead to severe side effects and potentially fatal results. Farag is ...

2021-01-07

Chemists have developed a nanomaterial that they can trigger to shape shift -- from flat sheets to tubes and back to sheets again -- in a controllable fashion. The Journal of the American Chemical Society published a description of the nanomaterial, which was developed at Emory University and holds potential for a range of biomedical applications, from controlled-release drug delivery to tissue engineering.

The nanomaterial, which in sheet form is 10,000 times thinner than the width of a human hair, is made of synthetic collagen. Naturally occurring collagen is the most abundant protein in humans, making the new material intrinsically biocompatible.

"No one has previously made collagen ...

2021-01-07

Alexandria, Va., USA -- The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted dental education and training. The study "COVID-19 and Dental and Dental Hygiene Students' Career Plans," published in the JDR Clinical & Translational Research (JDR CTR), examined the short-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dental hygiene and dental students' career intentions.

An anonymous online survey was emailed to dental and dental hygiene students enrolled at Virginia Commonwealth University School of Dentistry, Richmond, USA. The survey consisted of 81 questions that covered a wide range of topics including demographics, anticipated educational debt, career plans post-graduation, ...

2021-01-07

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- In almost all successful advertising campaigns, an appeal to emotion sparks a call-to-action that motivates viewers to become consumers. But according to research from a University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign expert who studies consumer information-processing and memory, emotionally arousing advertisements may not always help improve consumers' immediate memory.

A new paper co-written by Hayden Noel, a clinical associate professor of business administration at the Gies College of Business at Illinois, finds that an ad's emotional arousal can have a negative effect on immediate ...

2021-01-07

Using stem cells to regenerate parts of the skull, scientists corrected skull shape and reversed learning and memory deficits in young mice with craniosynostosis, a condition estimated to affect 1 in every 2,500 infants born in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The only current therapy is complex surgery within the first year of life, but skull defects often return afterward. The study, supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), could pave the way for more effective and less invasive therapies for children with craniosynostosis. ...

2021-01-07

Humans feeding leftover lean meat to wolves during harsh winters may have had a role in the early domestication of dogs, towards the end of the last ice age (14,000 to 29,000 years ago), according to a study published in Scientific Reports.

Maria Lahtinen and colleagues used simple energy content calculations to estimate how much energy would have been left over by humans from the meat of species they may have hunted 14,000 to 29,000 years that were also typical wolf prey species, such as horses, moose and deer. The authors hypothesized that if wolves and humans had hunted the same animals during harsh winters, humans would have killed wolves to reduce competition rather than domesticate them. With the exception of Mustelids such as weasels, ...

2021-01-07

"Nature red in tooth and claw" - The battle to survive is fought down to the level of our genes. Toxin-antidote elements are gene pairs that spread in populations by killing non-carriers. Now, research by the Burga lab at IMBA and the Kruglyak lab at the University of California, Los Angeles shows that these elements are more common in nature than first thought and have evolved a wide range of mechanisms to force their inheritance and propagate in populations - a parasite within the genome.

Originally described in the model nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, toxin-antidote elements consist of two linked genes, a toxin and its antidote. While the toxin is loaded into eggs by mothers, only embryos that inherit the element express the antidote. Thus, the ...

2021-01-07

The National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has released a new action agenda for a diverse genomics workforce. This ambitious set of goals, objectives, and implementation strategies details NHGRI's plans for enhancing the diversity of the genomics workforce by 2030.

"To reach its full potential, the field of genomics requires a workforce that better reflects the diversity of the U.S. population," NHGRI Director Eric Green, M.D., Ph.D., said. "Fostering an appropriately diverse genomics workforce of the future requires an immediate and substantial commitment ...

2021-01-07

Noncognitive skills and cognitive abilities are both important contributors to educational attainment -- the number of years of formal schooling that a person completes -- and lead to success across the life course, according to a new study from an international team led by researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, the University of Texas at Austin, and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. The research provides evidence for the idea that inheriting genes that affect things other than cognitive ability are important for understanding differences in people's life outcomes. Until now there had been questions about what these noncognitive skills are and how much they really matter for life outcomes. The new findings are published ...

2021-01-07

What The Study Did: Under a range of assumptions of presymptomatic transmission and transmission from individuals with infection who never develop symptoms, the model presented here estimated that more than half of transmission comes from asymptomatic individuals.

Author: Jay C. Butler, M.D., of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35057)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Intelligence deficit: Conclusion from the mouse to the human being

Researchers create an animal model for studying GPI anchor deficiencies