INFORMATION:

Original publication:

Eyal Ben-David et al.: "Ubiquitous selfish toxin-antidote elements in Caenorhabditis species". Current Biology, 2021.

About IMBA

IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology - is one of the leading biomedical research institutes in Europe focusing on cutting-edge stem cell technologies, functional genomics, and RNA biology. IMBA is located at the Vienna BioCenter, the vibrant cluster of universities, research institutes and biotech companies in Austria. IMBA is a subsidiary of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, the leading national sponsor of non-university academic research. The stem cell and organoid research at IMBA is being funded by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Science and the City of Vienna.

Selfish elements turn embryos into a battlefield

2021-01-07

(Press-News.org) "Nature red in tooth and claw" - The battle to survive is fought down to the level of our genes. Toxin-antidote elements are gene pairs that spread in populations by killing non-carriers. Now, research by the Burga lab at IMBA and the Kruglyak lab at the University of California, Los Angeles shows that these elements are more common in nature than first thought and have evolved a wide range of mechanisms to force their inheritance and propagate in populations - a parasite within the genome.

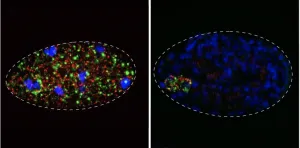

Originally described in the model nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, toxin-antidote elements consist of two linked genes, a toxin and its antidote. While the toxin is loaded into eggs by mothers, only embryos that inherit the element express the antidote. Thus, the offspring must inherit the element to survive. In this way, toxin-antidote pairs promote their own survival and spread in the population. This comes at great expense of their host's fitness - a quarter of their progeny, those that don't inherit the element, fall prey to the toxin.

Arrested development

"Before our study, only a handful of toxin-antidote pairs were known, and they were serendipitously discovered in different labs. We wondered: what if we actually go and look for these selfish elements, would they be rare or common?", says IMBA group leader Alejandro Burga. In their study, the teams of Burga and Kruglyak hunted for toxin-antidote pairs in a second nematode species Caenorhabditis tropicalis. The researchers identified five novel toxin-antidote pairs. Another selfish element was found in a third nematode species, C. briggsae. "This suggests that this class of selfish elements are not rare, but quite common in nematodes", explains Burga. Surprisingly, some of the newly identified toxin-antidote pairs do not act by disrupting embryonic development - like those identified in C. elegans - but rather kill non-carriers at a later stage of development. One element, which Burga and his team genetically dissected, does not even go as far as killing non-carriers. Instead, this selfish element delays the onset of reproduction in non-carriers. This turns out to be enough to allow the element to spread through the population. The researchers are now further investigating its mechanism of action.

Selfishness may support diversity

Burga and colleagues made another startling observation. The researchers found that different toxin-antidote pairs can be located on homologous chromosomes. "Because of this pairing, not only do we see a conflict between the selfish element and the individual, but also between selfish elements, which try to kill each other", says Burga. It is a war between selfish genes, but individuals get caught in the crossfire. "We hypothesize that selfish elements could have a direct role in speciation. At some point, carrying so many elements can just overwhelm their ability to produce viable offspring", adds Eyal Ben-David, co-first author of the study, now Assistant Professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. As a stark illustration of this, Burga and colleagues discovered that toxin-antidote elements can jointly cause defects in over 70% of the progeny from a single cross between two strains. "Such degree of incompatibility is likely insurmountable in the wild", says Ben-David.

Knowledge gained from studying toxin-antidote pairs could be used to improve gene drive systems. Synthetic gene drives have been engineered in the lab to control vector-borne disease, for instance, by spreading genes that affect the fertility of mosquitos. However, gene drives are often hampered by mutations, and more resilient systems are needed to ensure success, says Burga. "By studying selfish elements, which are natural gene drive systems, we hope we can engineer better synthetic ones in the near future. Selfish elements have evolved over thousands of years in nematodes and spread around the world - nature indeed is the best teacher," says Pinelopi Pliota, co-first author of the study.

Toxin-antidote pairs were first found in the 1980s in bacteria, and analogous elements have emerged in yeast, plants, insects and nematodes. "Toxin-antidote elements have independently evolved all over the tree of life. Either we humans are a unique case where they haven't evolved, or we haven't found them yet," says Burga.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NHGRI proposes an action agenda for building a diverse genomics workforce

2021-01-07

The National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has released a new action agenda for a diverse genomics workforce. This ambitious set of goals, objectives, and implementation strategies details NHGRI's plans for enhancing the diversity of the genomics workforce by 2030.

"To reach its full potential, the field of genomics requires a workforce that better reflects the diversity of the U.S. population," NHGRI Director Eric Green, M.D., Ph.D., said. "Fostering an appropriately diverse genomics workforce of the future requires an immediate and substantial commitment ...

Noncognitive skills -- distinct from cognitive abilities -- are important to success across the life

2021-01-07

Noncognitive skills and cognitive abilities are both important contributors to educational attainment -- the number of years of formal schooling that a person completes -- and lead to success across the life course, according to a new study from an international team led by researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, the University of Texas at Austin, and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. The research provides evidence for the idea that inheriting genes that affect things other than cognitive ability are important for understanding differences in people's life outcomes. Until now there had been questions about what these noncognitive skills are and how much they really matter for life outcomes. The new findings are published ...

SARS-CoV-2 transmission from people without COVID-19 symptoms

2021-01-07

What The Study Did: Under a range of assumptions of presymptomatic transmission and transmission from individuals with infection who never develop symptoms, the model presented here estimated that more than half of transmission comes from asymptomatic individuals.

Author: Jay C. Butler, M.D., of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35057)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and ...

Examining association of age, household dysfunction, outcomes in early adulthood

2021-01-07

What The Study Did: Population data from Denmark were used to examine whether age at exposure to negative experiences in childhood and adolescence (parents' unemployment, incarceration, mental disorders, death and divorce, and the child's foster care experiences) was associated with outcomes in early adulthood.

Author: Signe Hald Andersen, Ph.D., of the Rockwool Foundation Research Unit in Copenhagen, Denmark, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.32769)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, ...

Adapting to COVID-19 with outdoor intraocular pressure monitoring

2021-01-07

What The Study Did: To adapt to broader public health initiatives around COVID-19, researchers developed a drive-through intraocular pressure (IOP) screening clinic to minimize COVID-19 exposure for patients and clinicians by measuring eye pressure in the unconventional setting of a clinic parking lot.

Authors: Miel Sundararajan, M.D., of the University of California, San Francisco, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.6073)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article ...

Speech recognition changes after cochlear implant

2021-01-07

What The Study Did: Researchers compared changes in preoperative aided speech recognition with postoperative speech recognition among individuals who received cochlear implants.

Authors: Theodore R. McRackan, M.D., M.S.C.R., of the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2020.5094)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please ...

Virtual care at cancer center during COVID-19

2021-01-07

What The Study Did: The outcomes of a cancer center-wide virtual care program launched in response to the COVID-19 pandemic were examined in this study.

Authors: Alejandro Berlin, M.D., M.Sc., of the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6982)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict ...

Assessment of duplicate evidence in systematic reviews of imaging findings of children with COVID-19

2021-01-07

What The Study Did:This cross-sectional study maps a coronavirus research question to illustrate the overlap and shortcomings of the evidence syntheses in this area.

Author: Giordano Pérez-Gaxiola, M.D., M.Sc., of Sinaloa Pediatric Hospital's Cochrane Associate Centre in Culiacan, Mexico, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.32769)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: ...

Mount Sinai researchers identify and characterize 3 molecular subtypes of Alzheimer's

2021-01-07

(New York, NY - January 6, 2021) - Researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have identified three major molecular subtypes of Alzheimer's disease (AD) using data from RNA sequencing. The study advances our understanding of the mechanisms of AD and could pave the way for developing novel, personalized therapeutics.

The work was funded by the National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and published in Science Advances on January 6, 2021.

RNA is a genetic molecule similar to DNA that encodes the instructions for making proteins. RNA sequencing is a technology that reveals the presence and quantity of RNA in a biological sample such as a brain slice.

Alzheimer's ...

Unusual sex chromosomes of platypus, emu and duck

2021-01-07

Sex chromosomes are presumed to originate from a pair of identical ancestral chromosomes by acquiring a male- or a female-determining gene on one chromosome. To prevent the sex-determining gene from appearing in the opposite sex, recombination is suppressed on sex chromosomes. This leads to the degeneration of Y chromosome (or the W chromosome in case of birds) and the morphological difference of sex chromosomes between sexes. For example, the human Y chromosome bears only less than 50 genes, while the human X chromosome still maintains over 1500 genes from the autosomal ancestor. This process occurred independently in birds, in ...