(Press-News.org) ORLANDO, Jan. 8, 2021 - Florida's threatened coral reefs have a more than $4 billion annual economic impact on the state's economy, and University of Central Florida researchers are zeroing in on one factor that could be limiting their survival - coral skeleton strength.

In a new study published in the journal Coral Reefs, UCF engineering researchers tested how well staghorn coral skeletons withstand the forces of nature and humans, such as impacts from hurricanes and divers.

The researchers subjected coral skeletons to higher stresses than those caused by ocean waves, says Mahmoud Omer, a doctoral student in UCF's Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering and study co-author. "Under normal wave and tide regimes, a staghorn coral's skeleton will resist the physical forces exerted by the ocean waves. However, anthropogenic stressors such as harmful sunscreen ingredients, elevated ocean temperature, pollution and ocean acidification will weaken the coral skeleton and reduce its longevity."

Florida's coral reefs generate billions of dollars in local income, provide more than 70,000 jobs, protect the state's shorelines from storms and hurricanes, and support a diverse ecosystem of marine organisms, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The study uncovered a unique safety feature of the staghorn coral skeleton: Its porous design keeps the coral from being instantly crushed by an impact.

When the UCF engineers subjected skeleton samples to increasing stress, pores relieved the applied load and temporarily stalled further cracking and structural failure. The pores would "pop-in" and absorb some of the applied mechanical energy, thus preventing catastrophic failure. Although this ability has been shown in other coral species, this is the first time it's been demonstrated in staghorn coral.

"For the first time, we used the tools of mechanical engineering to closely examine the skeletons of a critically endangered coral raised in a coral nursery," says John Fauth, an associate professor in UCF's Department of Biology. "We now know more about the structure and mechanical performance of the staghorn coral skeleton than any other coral in the world. We can apply this knowledge to understand why staghorn coral restoration may work in some areas, but where their skeletons may fail due to human and environmental challenges in others."

The results provide baseline values that can be used to judge if nursery-reared staghorn coral have skeletons strong enough for the wild and to match them to areas with environmental conditions that best fit their skeleton strength.

Staghorn coral gets its name from the antler-like shape of its branches, which create an intricate underwater habitat for fish and reef organisms. It primarily is found in shallow waters around the Florida Keys, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and other Caribbean islands but has declined by more than 97 percent since the 1980s.

Although restoration efforts using transplanted, nursery-reared coral are underway, scientists continue working to increase their success rate.

Understanding coral skeleton structures also could inform development of skeletal structure replacements for humans, says Nina Orlovskaya, an associate professor in UCF's Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering. "Our findings are of high importance for development of novel and superior biostructures, which can be used as bone graft substitutes," Orlovskaya says. "Coral skeleton structures could be either chemically converted or 3D printed into bio-compatible calcium phosphate ceramics that one day might be directly used to regenerate bones in humans."

In addition to compression tests, the researchers analyzed mechanical properties and spectral and fluidic behavior. The spectral analysis used Raman microscopy, which allowed the researchers to map the effects of compression at the microscopic level in the coral skeleton.

Fluidic behavior analysis revealed that vortices formed around the coral colony helped it to capture food and transport respiratory gases and wastes.

The coral skeletons studied were from Nova Southeastern University's coral nursery, about one mile off the coast of Ft. Lauderdale, near Broward County, Florida. The corals were deceased and were from colonies that failed or were knocked loose during a storm.

INFORMATION:

Study co-authors also included Alejandro Carrasco-Pena, a graduate of UCF's mechanical engineering doctoral program; Bridget Masa, a graduate of UCF's mechanical engineering bachelor program; Zachary Shepard, a graduate of UCF's mechanical engineering bachelor program; Tyler Scofield, a graduate of UCF's mechanical engineering master's and bachelor program; Samik Bhattacharya, an assistant professor in UCF's Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering; Boyce E. Collins, a mechanical and chemical engineering scientist at North Carolina A&T State University; Sergey N. Yarmolenko, a senior research scientist at North Carolina A&T State University; Jagannathan Sankar, a distinguished university professor at North Carolina A&T State University; Ghatu Subhash, Ebaugh Professor in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at the University of Florida; and David S. Gilliam, an associate professor with Nova Southeastern University.

The research was funded in part by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Orlovskaya obtained her doctorate in materials science from the Institute for Problems of Materials Science at the Ukrainian National Academy of Sciences in Kyiv. She joined UCF in 2006.

Fauth received his doctorate in zoology from Duke University and joined UCF in 2003.

CONTACT:

Robert H. Wells,

Office of Research,

robert.wells@ucf.edu

A research team at the University of Basel has discovered immune cells resident in the lungs that persist long after a bout of flu. Experiments with mice have shown that these helper cells improve the immune response to reinfection by a different strain of the flu virus. The discovery could yield approaches to developing longer-lasting vaccinations against quickly-mutating viruses.

At the start of the coronavirus pandemic, some already began to raise the question of how long immunity lasts after weathering SARS-CoV-2. The same question has now arisen regarding the COVID-19 vaccination. A key role is played by immunological memory - a complex interplay of immune cells, antibodies and signaling ...

Humans have them, so do other animals and plants. Now research reveals that bacteria too have internal clocks that align with the 24-hour cycle of life on Earth.

The research answers a long-standing biological question and could have implications for the timing of drug delivery, biotechnology, and how we develop timely solutions for crop protection.

Biological clocks or circadian rhythms are exquisite internal timing mechanisms that are widespread across nature enabling living organisms to cope with the major changes that occur from day to night, even across seasons.

Existing inside cells, these molecular rhythms use external cues such as daylight and temperature to synchronise ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Efficiently mass-producing hydrogen from water is closer to becoming a reality thanks to Oregon State University College of Engineering researchers and collaborators at Cornell University and the Argonne National Laboratory.

The scientists used advanced experimental tools to forge a clearer understanding of an electrochemical catalytic process that's cleaner and more sustainable than deriving hydrogen from natural gas.

Findings were published today in Science Advances.

Hydrogen is found in a wide range of compounds on Earth, most commonly combining with oxygen to make water, and it has many scientific, industrial and energy-related roles. It also occurs in the form of hydrocarbons, compounds consisting of hydrogen and carbon such ...

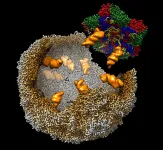

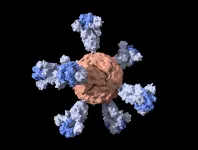

Researchers have for the first time identified the way viruses like the poliovirus and the common cold virus 'package up' their genetic code, allowing them to infect cells.

The findings, published today (Friday, 8 January) in the journal PLOS Pathogens by a team from the Universities of Leeds and York, open up the possibility that drugs or anti-viral agents can be developed that would stop such infections.

Once a cell is infected, a virus needs to spread its genetic material to other cells. This is a complex process involving the creation of what are known as virions - newly-formed infectious copies of the virus. Each virion is a protein shell containing a complete copy of the virus's genetic code. ...

Corals have evolved over millennia to live, and even thrive, in waters with few nutrients. In healthy reefs, the water is often exceptionally clear, mainly because corals have found ways to make optimal use of the few resources around them. Any change to these conditions can throw a coral's health off balance.

Now, researchers at MIT and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), in collaboration with oceanographers and marine biologists in Cuba, have identified microbes living within the slimy biofilms of some coral species that may help protect the coral against certain nutrient imbalances.

The team found these microbes can take up and ...

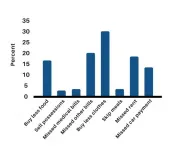

More than half of Latina mothers surveyed in Yolo and Sacramento counties reported making economic cutbacks in response to the pandemic shutdown last spring -- saying they bought less food and missed rent payments. Even for mothers who reported receiving the federal stimulus payment during this time, these hardships were not reduced, University of California, Davis, researchers found in a recent study.

"Latino families are fighting the pandemic on multiple fronts, as systemic oppression has increased their likelihood of contracting the virus, having complications from the virus and having significant economic hardship due to the virus," said Leah C. Hibel, associate professor of human development and family studies at UC Davis and ...

Like Peter Pan, some cells never grow up. In cancer, undifferentiated stem cells may help tumors such as glioblastoma become more aggressive than other forms of the disease. Certain groups of genes are supposed to help cells along the path to maturity, leaving their youthful "stemness" behind. This requires sweeping changes in the microRNAome -- the world of small non-coding material, known as microRNAs, that control where and when genes are turned on and off. Many microRNAs are tumor-suppressive; in cancer, the microRNAome is distorted and disrupted. Recent work by researchers at Brigham and Women's Hospital pinpoints critical changes in an enzyme known as DICER, which create a cascade of effects on this microRNAome. ...

The BioScience Talks podcast features discussions of topical issues related to the biological sciences.

In a career-spanning installment of the journal BioScience's In Their Own Words oral history series, Missouri Botanical Garden President Emeritus Peter Raven illuminates numerous topics, sharing insights related to the sustainability of human civilization, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the importance of science in addressing the world's greatest challenges.

Raven, a recent coauthor of "A Call to Action: Marshaling Science for Society," highlights the importance of public outreach in overcoming deeply rooted societal problems. Among them, he argues that our present economic system "sees natural productivity like every other ...

Before the pandemic, the lab of Stanford University biochemist Peter S. Kim focused on developing vaccines for HIV, Ebola and pandemic influenza. But, within days of closing their campus lab space as part of COVID-19 precautions, they turned their attention to a vaccine for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Although the coronavirus was outside the lab's specific area of expertise, they and their collaborators have managed to construct and test a promising vaccine candidate.

"Our goal is to make a single-shot vaccine that does not require a cold-chain for storage or transport. If we're successful at doing it ...

While rare, botulism can cause paralysis and is potentially fatal. It is caused by nerve-damaging toxins produced by Clostridium botulinum -- the most potent toxins known. These toxins are often found in contaminated food (home canning being a major culprit). Infants can also develop botulism from ingesting C. botulinum spores in honey, soil, or dust; the bacterium then colonizes their intestines and produces the toxin.

Once paralysis develops, there is no way to reverse it, other than waiting for the toxins to wear off. People with serious cases of botulism may need to be maintained on ventilators for weeks or months. But a new treatment approach and delivery vehicle, ...