(Press-News.org) For the brain to learn, retain memories, process sensory information, and coordinate body movements, its groups of nerve cells must generate coordinated electrical signals. Disorder in synchronous firing can impair these processes and, in extreme cases, lead to seizures and epilepsy.

Synchrony between neighboring neurons depends on the protein connexin 36, an essential element of certain types of synaptic connections that, unlike classical chemical synapses, pass signals between neurons through direct electrical connections. For more than 15 years, scientists have debated the tie between connexin 36 and epilepsy.

Now, a team of Virginia Tech scientists led by Yuchin Albert Pan, an associate professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC, have identified a new link between seizures and connexin 36 deficiency. The discovery, published today (Jan. 11, 2021) in Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience,, found that this interaction may make the brain more prone to having seizures.

Alyssa Brunal, a recent graduate of Virginia Tech's translational biology, medicine, and health doctoral program, working with her mentor Pan, developed new models for studying the relationship between connexin 36 and seizures and confirmed the relationship.

Zebrafish serve as a powerful animal model, allowing researchers to evaluate the effects of connexin 36 on the whole brain in an intact living system during neural hyperactivity.

As an essential component of electrically coupled synapses between neurons, connexin 36 plays an important role in rapid and synchronous activation of interconnected neworks of neurons within the brain, which is necessary for normal brain processes.

"In previous studies, people weren't using the same model organisms. They weren't looking at the same brain regions. They weren't using the same methods for inducing seizures," Brunal said. "I thought, because the zebrafish is such a versatile model organism, we could use it to try to discern what actually is going on."

Pan, who frequently uses larval zebrafish in studies, said the fish are ideal because they develop outside the womb, are translucent, and their entire brains are small enough to fit entirely under a microscope.

"Using modern microscopy techniques, we can see in an intact animal what is happening inside the brain," said Pan, who is also the research institute's Commonwealth Center for Innovative Technology Eminent Research Scholar in Developmental Neuroscience, and an associate professor in the department of biomedical sciences and pathobiology of the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine.

Brunal created dozens of whole-brain maps of zebrafish for the study.

The researchers used varying doses of a seizure-inducing drug, which causes neuronal hyperactivation, one of the main contributors to seizures. By comparing normal, wild-type zebrafish and mutant zebrafish with connexin 36 deficiencies, they found that connexin 36 deficiency altered the susceptibility to neuronal hyperactivity in a brain-region and drug-dose dependent manner.

Having established that a lack of connexin protein changed seizure susceptibility, they wondered if the hyperactivity associated with seizures, in turn, affected the expression of the protein. To test this, they applied the seizure-inducing drug to only the wild-type zebrafish, but this time, instead of looking for hyperactivity in the brain, they looked for expression of connexin 36. The results were striking.

The drug-induced hyperactivity caused an acute drop in connexin 36 levels across the brain, which recovered over time.

"I was like, holy cow, there's something actually happening to the protein. So not only is the protein affecting hyperactivity, we're also having some effect on the protein itself," Brunal said. "I think that's what really broke the project wide open."

The results were impressive, Pan said.

"A lot of times in science, you don't know what's going on until you painstakingly quantify the microscope images and see something that emerges from statistical analysis to a level of significance, but in one instance in this study, the connexin 36 was visibly gone," Pan said. "We thought, there's got to be something important there."

They applied a connexin 36-blocking drug on wild-type zebrafish, before administering the seizure-inducing drug. They compared the results to a control group of wild-type zebrafish that received only the seizure-inducing drug. The first group had significantly more neuronal hyperactivity, suggesting that an acute loss of connexin 36 may lead to more seizures.

While it's well known that having one seizure increases the likelihood of subsequent events, the mechanisms underlying this clinical phenomena are not well understood. This study describes a novel mechanism: seizures reduce connexin 36 levels in zebrafish models, and may contribute to the onset of subsequent seizures.

INFORMATION:

Pan, the principal investigator, and Brunal, who defended her doctoral dissertation based on the study's findings, are joined as authors on the paper by postdoctoral associate Kareem Clark, and research associate Manxiu Ma of the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute, and Ian Woods, an associate professor in the biology department of Ithaca College.

This study is funded by the Commonwealth Research Commercialization Fund and the Fralin Biomedical Reserch Institute.

They showed that a chronic connexin 36 deficiency in the mutant zebrafish made them more suspectible to brain hyperactivity, which in turn reduced the expression of connexin 36. Next, they wanted to know if the acute reduction of connexin 36 could predict the likelihood of future seizures.

Written by Matt Chittum, Virginia Tech

Many policymakers and educational institutions hope to boost their economies by stimulating students' entrepreneurial intentions. To date, most research concluded that entrepreneurship education could increase these intentions by improving the image that students have of entrepreneurship as a career option, making them see how their environment can help them become entrepreneurs or increasing their self-confidence regarding their entrepreneurial skills. However, recent studies show that even if these goals are achieved, students' entrepreneurial intentions often ...

HOUSTON - (Jan. 11, 2021) - Rice University scientists have extended their technique to produce graphene in a flash to tailor the properties of other 2D materials.

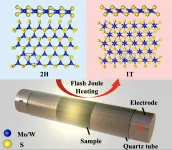

The labs of chemist James Tour and materials theorist Boris Yakobson reported in the American Chemical Society's ACS Nano they have successfully "flashed" bulk amounts of 2D dichalcogenides, changing them from semiconductors to metallics.

Such materials are valuable for electronics, catalysis and as lubricants, among other applications.

The process employs flash Joule heating -- using an electrical charge to dramatically raise the material's temperature -- to convert semiconducting molybdenum disulfide and tungsten disulfide. The duration of the pulse and select additives can also control the now-metallic products' ...

DURHAM, N.C. - A Duke-led team of scientists has developed a bio-compatible surgical patch that releases non-opioid painkillers directly to the site of a wound for days and then dissolves away.

The polymer patch provides a controlled release of a drug that blocks the enzyme COX-2 (cyclooxygenase-2,) which drives pain and inflammation. The study appears Jan. 10, 2021 in the Journal of Controlled Release.

When they started "We were making hernia meshes and different antimicrobial films," said Matthew Becker, the Hugo L. Blomquist professor chemistry at Duke, and last author on the paper. "We thought you could potentially put pain drugs or anesthetics in the film if you ...

A shapeshifting immune system protein called XCL1 evolved from a single-shape ancestor hundreds of millions of years ago. Now, researchers at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) discovered the molecular basis for how this happened. In the process they uncovered principles that scientists can use to design purpose-built nanoscale transformers for use as biosensors, components of molecular machines, and even therapeutics. The findings were published today in Science. The primary and senior authors of the manuscript, respectively, are MCW researchers Acacia Dishman, MD-PhD student, and Brian Volkman, PhD, professor of biochemistry.

Molecular switches can be used to detect cancer, construct nanoscale machines, and even build cellular computers. ...

Scientists crafting a nickel-based catalyst used in making hydrogen fuel built it one atomic layer at a time to gain full control over its chemical properties. But the finished material didn't behave as they expected: As one version of the catalyst went about its work, the top-most layer of atoms rearranged to form a new pattern, as if the square tiles that cover a floor had suddenly changed to hexagons.

But that's ok, they reported today, because understanding and controlling this surprising transformation gives them a new way to turn catalytic activity on and off and make good catalysts ...

Women who use marijuana could have a more difficult time conceiving a child than women who do not use marijuana, suggests a study by researchers at the National Institutes of Health. Marijuana use among the women's partners--which could have influenced conception rates--was not studied. The researchers were led by Sunni L. Mumford, Ph.D., of the Epidemiology Branch in NIH's Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The study appears in Human Reproduction.

The women were part of a larger group trying to conceive after one or two prior miscarriages. Women who said they used cannabis products--marijuana or hashish--in the weeks before pregnancy, or who had positive urine tests for cannabis ...

Scientists have used a "galaxy-sized" space observatory to find possible hints of a unique signal from gravitational waves, or the powerful ripples that course through the universe and warp the fabric of space and time itself.

The new findings, which appeared recently in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, hail from a U.S. and Canadian project called the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves (NANOGrav).

For over 13 years, NANOGrav researchers have pored over the light streaming from dozens of pulsars spread throughout the Milky ...

Nothing in biology is static. Biological processes fluctuate over time, and if we are to put together an accurate picture of cells, tissues, organs etc., we have to take into account their temporal patterns. In fact, this effort has given rise to an entire field of study known as "chronobiology".

The liver is a prime example. Everything we eat or drink is eventually processed there to separate nutrients from waste and regulate the body's metabolic balance. In fact, the liver as a whole is extensively time-regulated, and this pattern is orchestrated by the so-called ...

EAST LANSING, Mich. - Michigan State University is leading a global research effort to offer the first worldwide view of how climate change could affect water availability and drought severity in the decades to come.

By the late 21st century, global land area and population facing extreme droughts could more than double -- increasing from 3% during 1976-2005 to 7%-8%, according to Yadu Pokhrel, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering in MSU's College of Engineering, and lead author of the research published in Nature Climate Change.

"More and more people will suffer from extreme droughts if a medium-to-high level of global warming ...

Researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health developed an infectious disease early warning system that includes areas lacking health clinics participating in infectious disease surveillance. The approach compensates for existing gaps by optimally assigning surveillance sites that support better observation and prediction of the spread of an outbreak, including to areas remaining without surveillance. Details are published in the journal Nature Communications.

The research team, including Jeffrey Shaman and Sen Pei, have been at the forefront of forecasting and analyzing the spread of COVID-19. Their ...