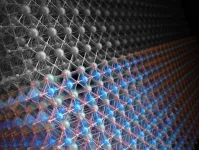

(Press-News.org) Scientists crafting a nickel-based catalyst used in making hydrogen fuel built it one atomic layer at a time to gain full control over its chemical properties. But the finished material didn't behave as they expected: As one version of the catalyst went about its work, the top-most layer of atoms rearranged to form a new pattern, as if the square tiles that cover a floor had suddenly changed to hexagons.

But that's ok, they reported today, because understanding and controlling this surprising transformation gives them a new way to turn catalytic activity on and off and make good catalysts even better.

The research team, led by scientists from Stanford University and the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, described their study in Nature Materials today.

"Catalysts can change very quickly during the course of a reaction, and understanding how they transform from an inactive phase to an active one is crucial to designing more efficient catalysts," said Will Chueh, an investigator with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) at SLAC who led the study. "This transformation gives us the equivalent of a knob we can turn to fine-tune their behavior."

Splitting water to make hydrogen fuel

Catalysts help molecules react without being consumed in the reaction, so they can be used over and over. They're the backbone of many green-energy devices.

This particular catalyst, lanthanum nickel oxide or LNO, is used to split water into hydrogen and oxygen in a reaction powered by electricity. It's the first step in generating hydrogen fuel, which has enormous potential for storing renewable energy from sunlight and other sources in a liquid form that's energy-rich and easy to transport. In fact, several manufacturers have already produced electric cars powered by hydrogen fuel cells.

But this first step is also the most difficult one, said Michal Bajdich, a theorist at the SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis at SLAC, and researchers have been searching for inexpensive materials that will carry it out more efficiently.

Since reactions take place on a catalyst's surface, researchers have been trying to precisely engineer those surfaces so they promote only one specific chemical reaction with high efficiency.

Building materials one atomic layer at a time

The LNO investigated in this study belongs to a class of promising catalytic materials known as perovskites, named after a natural mineral with a similar atomic structure.

Christoph Baeumer, who came to SLAC as a Marie Curie Fellow from Aachen University in Germany to carry out the study, prepared LNO in what's known as an epitaxial thin film - a film grown in atomically thin layers in a way that creates an extraordinarily precise arrangement of atoms.

Dividing his time between California and Germany, Baeumer made two versions of the film at different temperatures - one with a nickel-rich surface and another with a lanthanum-rich surface. Then the research team ran all the versions through the water-splitting reaction to compare how well they performed.

"We were surprised to discover that the films with nickel-rich surfaces carried out the reaction twice as fast," Baeumer said.

Tuning a catalyst's surface for better performance

To find out why, the team took the films to DOE's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, where a group led by Slavomir Nemsak looked at their atomic structure with X-rays at the Advanced Light Source.

"It was surprising that the difference between the 'good' and the 'bad' catalyst was only in the last atomic layer of the films," Nemsak said. Those investigations also revealed that in films with nickel-rich surface layers that were prepared at cooler temperatures, the top layer of atoms transformed at some point during the water-splitting reaction, and this new arrangement boosted the catalytic activity.

Meanwhile, Jiang Li, a postdoctoral researcher and theorist at SUNCAT, performed computational studies of this very complex system using Berkeley Lab's National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC). His conclusions agreed with the experimental results, predicting that the version of the catalyst with the transformed surface - from a cubic pattern to a hexagonal one - would be the most active and stable one.

Bajdich said, "Is the transformation of the nickel-rich surface driven by the way the catalyst is prepared, or by changes it undergoes while it carries out the water-splitting reaction? That's very hard to answer. It looks like both have to occur."

Although this particular catalyst is not the best in the world for splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen, he said, discovering how a surface transformation boosts its activity is important and could potentially apply to other materials too.

"If we can unlock the secrets of this transformation so we can accurately tune it," he said, "then we can leverage this phenomenon to make much better catalysts in the future."

INFORMATION:

The Advanced Light Source and the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center are DOE Office of Science user facilities. Scientists from Forschungszentrum Juelich in Germany also contributed to this research. The project was funded by the DOE Office of Science, and Baeumer was also supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program through a Marie Sklodowska-Curie fellowship.

Citation: Christoph Baeumer et al., Nature Materials, 11 January 2020 (10.1038/s41563-020-00877-1)

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.

Women who use marijuana could have a more difficult time conceiving a child than women who do not use marijuana, suggests a study by researchers at the National Institutes of Health. Marijuana use among the women's partners--which could have influenced conception rates--was not studied. The researchers were led by Sunni L. Mumford, Ph.D., of the Epidemiology Branch in NIH's Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The study appears in Human Reproduction.

The women were part of a larger group trying to conceive after one or two prior miscarriages. Women who said they used cannabis products--marijuana or hashish--in the weeks before pregnancy, or who had positive urine tests for cannabis ...

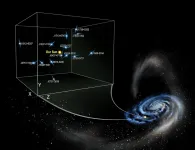

Scientists have used a "galaxy-sized" space observatory to find possible hints of a unique signal from gravitational waves, or the powerful ripples that course through the universe and warp the fabric of space and time itself.

The new findings, which appeared recently in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, hail from a U.S. and Canadian project called the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves (NANOGrav).

For over 13 years, NANOGrav researchers have pored over the light streaming from dozens of pulsars spread throughout the Milky ...

Nothing in biology is static. Biological processes fluctuate over time, and if we are to put together an accurate picture of cells, tissues, organs etc., we have to take into account their temporal patterns. In fact, this effort has given rise to an entire field of study known as "chronobiology".

The liver is a prime example. Everything we eat or drink is eventually processed there to separate nutrients from waste and regulate the body's metabolic balance. In fact, the liver as a whole is extensively time-regulated, and this pattern is orchestrated by the so-called ...

EAST LANSING, Mich. - Michigan State University is leading a global research effort to offer the first worldwide view of how climate change could affect water availability and drought severity in the decades to come.

By the late 21st century, global land area and population facing extreme droughts could more than double -- increasing from 3% during 1976-2005 to 7%-8%, according to Yadu Pokhrel, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering in MSU's College of Engineering, and lead author of the research published in Nature Climate Change.

"More and more people will suffer from extreme droughts if a medium-to-high level of global warming ...

Researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health developed an infectious disease early warning system that includes areas lacking health clinics participating in infectious disease surveillance. The approach compensates for existing gaps by optimally assigning surveillance sites that support better observation and prediction of the spread of an outbreak, including to areas remaining without surveillance. Details are published in the journal Nature Communications.

The research team, including Jeffrey Shaman and Sen Pei, have been at the forefront of forecasting and analyzing the spread of COVID-19. Their ...

Fast facts:

This study describes essential differences between marine and freshwater species and the contributions of viruses to such differences

The results may help guide future bioengineering efforts to develop plant strains adapted to grow in salt-water, which is of local and regional food security interest

Microalgae are fundamental to global ecosystems due to their ability to sustain coral reef species and produce atmospheric oxygen

Before this study, many important algal phyla did not have sequenced representatives

Viruses have contributed to the evolution of algae and their genome makeups

Abu Dhabi, UAE, January 11, 2021: NYU Abu Dhabi (NYUAD) ...

It is well known that the expansion of the universe is accelerating due to a mysterious dark energy. Within galaxies, stars also experience an acceleration, though this is due to some combination of dark matter and the stellar density. In a new study to be published in Astrophysical Journal Letters researchers have now obtained the first direct measurement of the average acceleration taking place within our home galaxy, the Milky Way. Led by Sukanya Chakrabarti at the Institute for Advanced Study with collaborators from Rochester Institute of Technology, University of Rochester, and ...

Moms are not more likely than other women to support gun control efforts. In fact, a new study finds that parenthood doesn't have a substantial effect on the gun control views of men or women.

"Everybody 'knows' that moms are more politically liberal on gun control issues," says Steven Greene, corresponding author of the study and a professor of political science at North Carolina State University. "We wanted to know if that's actually true. And, as it turns out, it's not true - which was surprising."

To explore the impact of parenthood on people's gun control views, the researchers drew on data collected by the Pew Center for Research in 2017 as part of Pew's nationally ...

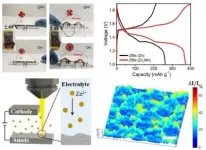

Lithium-ion batteries are critical for modern life, from powering our laptops and cell phones to those new holiday toys. But there is a safety risk - the batteries can catch fire.

Zinc-based aqueous batteries avoid the fire hazard by using a water-based electrolyte instead of the conventional chemical solvent. However, uncontrolled dendrite growth limits their ability to provide the high performance and long life needed for practical applications.

Now researchers have reported in Nature Communications that a new 3D zinc-manganese nano-alloy anode has overcome the limitations, resulting in a stable, high-performance, dendrite-free aqueous battery using seawater ...

In diseases characterized by bone loss -such as periodontitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoporosis- there is a lot that scientists still don't understand. What is the role of the immune response in the process? What happens to the regulatory mechanisms that protect bone?

In a paper published recently in Scientific Reports, researchers from the Forsyth Institute and the Universidad de Chile describe a mechanism that unlocks a piece of the puzzle. Looking at periodontal disease in a mouse model, scientists found that a specific type of T cell, known as regulatory T cells, start behaving in unexpected ways. These cells lose their ability to regulate bone ...