(Press-News.org) UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Wild bees are more affected by climate change than by disturbances to their habitats, according to a team of researchers led by Penn State. The findings suggest that addressing land-use issues alone will not be sufficient to protecting these important pollinators.

"Our study found that the most critical factor influencing wild bee abundance and species diversity was the weather, particularly temperature and precipitation," said Christina Grozinger, Distinguished Professor of Entomology and director of the Center for Pollinator Research, Penn State. "In the Northeastern United States, past trends and future predictions show a changing climate with warmer winters, more intense precipitation in winter and spring, and longer growing seasons with higher maximum temperatures. In almost all of our analyses, these conditions were associated with lower abundance of wild bees, suggesting that climate change poses a significant threat to wild bee communities."

According to Melanie Kammerer, graduate student in entomology, Penn State, few studies have considered the effects of both climate and land use on wild bees.

"We thought this was an oversight because, like many organisms, bees are experiencing habitat loss and climate change simultaneously," she said. "By looking at both factors in the same study, we were able to compare the relative importance of these two stressors."

To conduct their study, the researchers analyzed a 14-year United States Geological Survey data set of wild bee occurrences from more than 1,000 locations in Maryland, Delaware and Washington, D.C., specifically examining how different bee species and communities respond to land-use and climate factors.

"To really understand the effects of weather and climate, particularly as weather patterns become more variable with climate change, we need to use these very large, long-term data sets," said Grozinger. "We hope that our study, and others like it, will help encourage the collection and integration of these data sets for future research."

Using land cover maps and spatial models, the team described the landscape surrounding each of the sampling locations, including the habitat size and available floral and nesting resources. The team's results appear today (Jan. 12) in Global Change Biology. Finally, the researchers compiled a large suite of climate variables and used machine-learning models to identify the most important variables and to quantify their effects on wild bees.

"We found that temperature and precipitation patterns are very important drivers of wild bee communities in our study, more important than the amount of suitable habitat or floral and nesting resources in the landscape," said Kammerer.

Interestingly, added Grozinger, different bee species were most affected by different weather conditions. For example, she said, areas with more rain had fewer spring bees.

"We think the rain limits the ability of spring bees to collect food for their offspring," said Grozinger. "Similarly, a very hot summer, which might reduce flowering plants, was associated with fewer summer bees the next year."

In addition, warm winters led to reduced numbers of some bee species.

"This result coincides with studies showing that, with earlier spring onset, overwintering adults had higher pre-emergence weight loss and mortality and shorter life span post-emergence," Grozinger said.

Kammerer noted that these weather changes will likely worsen in the coming years.

"In the future, warm winters and long, hot summers are predicted to occur more frequently, which we expect will be a serious challenge to wild-bee populations," she said. "We are just beginning to understand the many ways that climate influences bees, but in order to conserve these essential pollinators, we need to figure out when, where and how changing climate disrupts bee life cycles, and we need to move from considering single stressors to quantifying multiple, potentially interacting pressures on wild-bee communities."

According to the researchers, the study is part of the their larger Beescape project, which allows individuals -- including growers, conservationists and gardeners -- to explore the landscape quality at their site and potentially make adjustments to improve conditions for bees. Given their new findings, the researchers plan to expand Beescape to include weather and climate conditions.

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the paper include Sarah Goslee, ecologist, United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service; Margaret Douglas, assistant professor of environmental studies, Dickinson College; and John Tooker, professor of entomology, Penn State.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture National Institute for Food and Agriculture, the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research and the College of Agricultural Sciences and Intercollege Graduate Degree Program in Ecology at Penn State supported this research.

A major risk of being hospitalised is catching a bacterial infection.

Hospitals, especially areas including intensive care units and surgical wards, are teeming with bacteria, some of which are resistant to antibiotics - they are infamously known as 'superbugs'.

Superbug infections are difficult and expensive to treat, and can often lead to dire consequences for the patient.

Now, new research published today in the prestigious journal Nature Microbiology has discovered how to revert antibiotic-resistance in one of the most dangerous superbugs.

The strategy involves ...

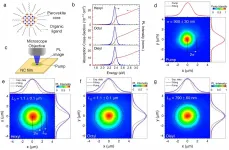

Producing clean energy and reducing the power consumption of illumination and personal devices are key challenges to reduce the impact of modern civilization on the environment. As a result, the surging demand for solar cells and light-emitting devices is driving scientists to explore new semiconductor materials and improve their performances, while lowering the production costs.

Semiconductor nanocrystals (materials with sizes about 10 nanometers, which is approximately 10,000 times thinner than our hair) hold great promise for these applications: they are cheap to produce, can be easily integrated in these devices and possess exceptionally enhanced properties upon interaction with ...

Curtin University researchers have used ancient crystals from eroded rocks found in stream sediments in Greenland to successfully test the theory that portions of Earth's ancient crust acted as 'seeds' from which later generations of crust grew.

The findings not only advance an understanding of the production of the Earth's crust through deep time, along with its structure and composition, but reveal a planet-wide crustal growth spurt three billion years ago when mantle temperatures peaked.

Lead author Professor Chris Kirkland, from Curtin University's Timescales of Mineral Systems ...

You are likely familiar with the serious consequences of anorexia for those who experience it, but you might not be aware that the disorder may not be purely psychological. A recent review from researchers at the University of Oxford in the open-access journal END ...

Highlights:

Severe cases of COVID-19 often include GI symptoms

Chronic diseases associated with severe COVID-19 are also associated with altered gut microbiota

A growing body of evidence suggests poor gut health adversely affects prognosis

If studies do empirically demonstrate a connection between the gut microbiota and COVID-19 severity, then interventions like probiotics or fecal transplants may help patients

Washington, D.C. - January 12, 2021 - People infected with COVID-19 experience a wide range of symptoms and severities, the most commonly reported including high fevers ...

PHILADELPHIA -- (Jan. 12, 2021) -- Scientists at The Wistar Institute have created an advanced humanized immune system mouse model that allows them to examine resistance to immune checkpoint blockade therapies in melanoma. It has revealed a central role for mast cells. These findings were published today in the journal Nature Communications.

Checkpoint inhibitors revolutionized therapeutic options for advanced melanoma. However, only a fraction of patients respond to this treatment and some relapse due to reemergence of therapy-resistant lesions.

"To better understand why some cancers do not respond or become resistant to checkpoint therapies, ...

Imagine you gave the exact same art pieces to two different groups of people and asked them to curate an art show. The art is radical and new. The groups never speak with one another, and they organize and plan all the installations independently. On opening night, imagine your surprise when the two art shows are nearly identical. How did these groups categorize and organize all the art the same way when they never spoke with one another?

The dominant hypothesis is that people are born with categories already in their brains, but a study from the Network Dynamics Group (NDG) at the Annenberg School for Communication has discovered a novel explanation. In an experiment in which people were asked to categorize unfamiliar shapes, individuals and small groups created ...

New research has found as climate change causes the world's oceans to warm, baby sharks are born smaller, exhausted, undernourished and into environments that are already difficult for them to survive in.

Lead author of the study Carolyn Wheeler is a PhD candidate at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University (Coral CoE at JCU) and the University of Massachusetts. She examined the effects of increased temperatures on the growth, development and physiological performance of epaulette sharks--an egg-laying species found only ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - An unfortunate truth about the use of mechanical ventilation to save the lives of patients in respiratory distress is that the pressure used to inflate the lungs is likely to cause further lung damage.

In a new study, scientists identified a molecule that is produced by immune cells during mechanical ventilation to try to decrease inflammation, but isn't able to completely prevent ventilator-induced injury to the lungs.

The team is working on exploiting that natural process in pursuit of a therapy that could lower the chances for lung damage in patients on ventilators. Delivering high levels of the helpful molecule with a nanoparticle was effective ...

Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, January 12, 2020: New research from NYU Abu Dhabi's Laboratory of Neural Systems and Behavior for the first time used an animal model to demonstrate how abnormal sleep architecture can be a predictor of stress vulnerability. These important findings have the potential to inform the development of sleep tests that can help identify who may be susceptible -- or resilient -- to future stress.

In the study, Abnormal Sleep Signals Vulnerability to Chronic Social Defeat Stress, which appears in the journal Frontiers in Neuroscience, NYUAD Assistant Professor of Biology Dipesh Chaudhury and Research Associate Basma Radwan describe their development of a mouse ...