(Press-News.org) EUGENE, Ore. -- Jan. 12, 2020 -- Insufficient interactions with academic advisors and peers and financial problems are derailing career aspirations of women and minority groups pursing graduate degrees in the nation's highest-funded chemistry programs.

The challenges, tied to systemic gender and racial inequities, emerged from a deep analysis of data compiled in a 2013 American Chemical Society survey of 1,375 chemistry graduate students in the top 100 university chemistry departments in terms of research funding reported by the National Science Foundation.

The findings are detailed in a study, led by University of Oregon researchers, publishing this week in the online ahead of print in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"I think this is a wake-up call to chemistry departments around the country and especially our most highly ranked departments," said study co-author Geraldine Richmond, a professor of chemistry and the UO's Presidential Chair in Science. "Many graduate students are not getting the quality of support in advising and mentorship that are documented to be essential for a success in the early career stages."

The findings, she added, shed light on gender and racial inequities in U.S. chemistry graduate programs that are at the heart of lower retention and completion of doctoral degrees for underrepresented groups in chemistry.

As a result of the inequities, women, especially, "are more likely to drop out and not go on to chase their dream to become professors of tomorrow," said the study's lead author, sociologist Jean Stockard, professor emerita of the UO's School of Planning, Public Policy and Management.

The research team warns that the troubling graduate school experiences mirror inequities in other areas of society and threaten the goal of diversifying the STEM fields of science, technology, engineering and math.

The study's third co-author is chemist Celeste M. Rohlfing, former chief operating officer of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and former deputy assistant director of the National Science Foundation.

"Women identifying as URM (underrepresented minorities) were least likely to report that their advisors encouraged them to take challenges or pursue their goals, advocated for them, gave credit for their contributions, created a 'fair environment,' gave regular feedback, engaged them in writing proposals and giving presentations, helped develop professional relationships, or indicated that they were satisfied with the student's work," the three co-authors wrote.

The ACS survey had revealed that women and member of other marginalized groups had periodic significant differences in their experiences. Stockard dug deeper into the data, using multivariate statistical analyses, to parse out variations of experiences among women and men and women from African American, Latinx and Native American groups.

Women identifying as members of a marginalized group more often reported negative experiences with advisors than did their majority group colleagues. Women not in such groups were not far behind them in their responses.

Men in marginalized groups involved in chemistry research groups reported that they received less supportive peer interactions with fellow graduate students and postdoctoral researchers. Navigating such interactions, Stockard said, is vital for building opportunities to collaborate on projects and forge publishing co-authorships.

In another finding, men and women in marginalized groups were more than twice as likely than those in majority groups to report inadequate financial support to meet the cost of living where they live. They also were more likely to have to supplement their income with loans and personal resources. The discrepancy, the researchers suggest, may reflect economic disparities in the society as a whole.

"On average, the accumulated wealth of families from marginalized communities is only a small fraction of others," Stockard said. "Thus, these students may be far less likely to receive help from their parents when times become difficult."

A national response is needed to reduce the financial hardships and the problems in peer and advisor relationships, the researchers concluded.

"We need change at all levels," said Richmond, who heads the Committee on the Advancement of Women Chemists, known internationally as COACh, which she co-founded in 1997 with the goal of increasing the number and career success of women scientists and engineers worldwide.

"We need to recognize that our graduate students are not just hired hands or technicians. We need to treat them like professionals," she said. "That means pay them like professionals. This is a serious national issue. We are losing talent that we cannot afford to lose."

INFORMATION:

Stockard and Rohlfing are long-time collaborators in supporting COACh.

Links:

About Geraldine "Geri" Richmond:

https://richmondscience.uoregon.edu/

About Jean Stockard:

https://pppm.uoregon.edu/pppm/jean-stockard

UO Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry:

https://chemistry.uoregon.edu/

About COACh:

https://coach.uoregon.edu/

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Wild bees are more affected by climate change than by disturbances to their habitats, according to a team of researchers led by Penn State. The findings suggest that addressing land-use issues alone will not be sufficient to protecting these important pollinators.

"Our study found that the most critical factor influencing wild bee abundance and species diversity was the weather, particularly temperature and precipitation," said Christina Grozinger, Distinguished Professor of Entomology and director of the Center for Pollinator Research, Penn State. "In the Northeastern United States, past trends and future predictions show a changing climate with warmer winters, more intense precipitation ...

A major risk of being hospitalised is catching a bacterial infection.

Hospitals, especially areas including intensive care units and surgical wards, are teeming with bacteria, some of which are resistant to antibiotics - they are infamously known as 'superbugs'.

Superbug infections are difficult and expensive to treat, and can often lead to dire consequences for the patient.

Now, new research published today in the prestigious journal Nature Microbiology has discovered how to revert antibiotic-resistance in one of the most dangerous superbugs.

The strategy involves ...

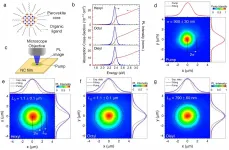

Producing clean energy and reducing the power consumption of illumination and personal devices are key challenges to reduce the impact of modern civilization on the environment. As a result, the surging demand for solar cells and light-emitting devices is driving scientists to explore new semiconductor materials and improve their performances, while lowering the production costs.

Semiconductor nanocrystals (materials with sizes about 10 nanometers, which is approximately 10,000 times thinner than our hair) hold great promise for these applications: they are cheap to produce, can be easily integrated in these devices and possess exceptionally enhanced properties upon interaction with ...

Curtin University researchers have used ancient crystals from eroded rocks found in stream sediments in Greenland to successfully test the theory that portions of Earth's ancient crust acted as 'seeds' from which later generations of crust grew.

The findings not only advance an understanding of the production of the Earth's crust through deep time, along with its structure and composition, but reveal a planet-wide crustal growth spurt three billion years ago when mantle temperatures peaked.

Lead author Professor Chris Kirkland, from Curtin University's Timescales of Mineral Systems ...

You are likely familiar with the serious consequences of anorexia for those who experience it, but you might not be aware that the disorder may not be purely psychological. A recent review from researchers at the University of Oxford in the open-access journal END ...

Highlights:

Severe cases of COVID-19 often include GI symptoms

Chronic diseases associated with severe COVID-19 are also associated with altered gut microbiota

A growing body of evidence suggests poor gut health adversely affects prognosis

If studies do empirically demonstrate a connection between the gut microbiota and COVID-19 severity, then interventions like probiotics or fecal transplants may help patients

Washington, D.C. - January 12, 2021 - People infected with COVID-19 experience a wide range of symptoms and severities, the most commonly reported including high fevers ...

PHILADELPHIA -- (Jan. 12, 2021) -- Scientists at The Wistar Institute have created an advanced humanized immune system mouse model that allows them to examine resistance to immune checkpoint blockade therapies in melanoma. It has revealed a central role for mast cells. These findings were published today in the journal Nature Communications.

Checkpoint inhibitors revolutionized therapeutic options for advanced melanoma. However, only a fraction of patients respond to this treatment and some relapse due to reemergence of therapy-resistant lesions.

"To better understand why some cancers do not respond or become resistant to checkpoint therapies, ...

Imagine you gave the exact same art pieces to two different groups of people and asked them to curate an art show. The art is radical and new. The groups never speak with one another, and they organize and plan all the installations independently. On opening night, imagine your surprise when the two art shows are nearly identical. How did these groups categorize and organize all the art the same way when they never spoke with one another?

The dominant hypothesis is that people are born with categories already in their brains, but a study from the Network Dynamics Group (NDG) at the Annenberg School for Communication has discovered a novel explanation. In an experiment in which people were asked to categorize unfamiliar shapes, individuals and small groups created ...

New research has found as climate change causes the world's oceans to warm, baby sharks are born smaller, exhausted, undernourished and into environments that are already difficult for them to survive in.

Lead author of the study Carolyn Wheeler is a PhD candidate at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University (Coral CoE at JCU) and the University of Massachusetts. She examined the effects of increased temperatures on the growth, development and physiological performance of epaulette sharks--an egg-laying species found only ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - An unfortunate truth about the use of mechanical ventilation to save the lives of patients in respiratory distress is that the pressure used to inflate the lungs is likely to cause further lung damage.

In a new study, scientists identified a molecule that is produced by immune cells during mechanical ventilation to try to decrease inflammation, but isn't able to completely prevent ventilator-induced injury to the lungs.

The team is working on exploiting that natural process in pursuit of a therapy that could lower the chances for lung damage in patients on ventilators. Delivering high levels of the helpful molecule with a nanoparticle was effective ...