(Press-News.org) Scientists from the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA have developed a technique that will enable researchers to more efficiently isolate and identify rare T cells that are capable of targeting viruses, cancer and other diseases.

The approach could increase scientists' understanding of how these critical immune cells respond to a wide range of illnesses and advance the development of T cell therapies. This includes immunotherapies that aim to boost the function and quantity of cancer or virus-targeting T cells and therapies intended to regulate the activity of T cells that are overactive in autoimmune diseases such as diabetes and multiple sclerosis.

The study, published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, describes how the new method, called CLInt-Seq, combines and improves upon existing techniques to collect and genetically sequence rare T cells.

"T cells are critical for protecting the body against both infections and cancers," said Pavlo Nesterenko, first author of the new paper and a graduate student in the lab of Dr. Owen Witte. "They're both the effectors and organizers of the body's adaptive immune response, which means they can be used as therapeutics and studying their dynamics can shed light on overall immune activity."

T cells stand out from other immune cells because they are equipped with molecules on their surfaces called T-cell receptors that recognize fragments of foreign proteins called antigens.

Our bodies produce millions and millions of T cells per day and each of these cells has its own distinct set of receptors. Every T-cell receptor is capable of recognizing one specific antigen. One T-cell receptor might recognize an antigen from the virus that causes the common cold while another might recognize an antigen from breast cancer, for example.

When a T cell encounters an antigen its receptor recognizes, it springs to action, producing large numbers of copies of itself and instructing other parts of the immune system to attack cells bearing that antigen.

Researchers around the world are exploring methods to collect T cells with receptors targeting cancer or other illnesses like the SARS-CoV-2 virus from patients, expand those cells in the lab and then return this larger population of targeted T cells to patients to boost their immune response.

"The problem is that in most populations of cells we have access to, whether it be from peripheral blood or samples taken from other parts of the human body, T cells with receptors of interest are found in very low numbers," said Witte, senior author of the paper and founding director of the UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center. "Existing methods for capturing and identifying these T cells are labor-intensive and need improvement."

Part of the reason this process is inefficient is that when T cells recognize the antigen for which they have the corresponding receptor, they send out signals that prompt other cells nearby to partially activate.

"These so-called bystander cells are excited by the activity around them, but are not really capable of reacting to the antigen that provoked the immune response," said Witte, who holds the presidential chair in developmental immunology in the department of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics and is a member of the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

When researchers attempt to isolate T cells with specific receptors using traditional methods, they end up capturing many of these bystander cells. CLInt-Seq alleviates this problem by incorporating a technique that enables researchers to distinguish T cells with receptors of interest from most bystander cells.

Isolating T cells with specific receptors is only the first step. In order for these isolated cells to be useful, they need to be analyzed using droplet-based mRNA sequencing, also known as Drop-seq, which can measure messenger RNA expression in thousands of individual cells at once.

"Once you know the sequence of a T-cell receptor of interest, you can use that information to develop therapies that either make more of that cell in the case of fighting cancer and viruses or introduce regulatory T cells with this receptor sequence to curb an overactive immune response in a given area," Nesterenko said.

The process of isolating T cells with specific receptors requires that the cells' contents are fixed in place using chemicals that form bonds between the proteins inside each cell and their surroundings - this technique is known as cross-linking. Unfortunately, cross-linking degrades the T cells' RNA, which makes Drop-seq analysis very challenging. CLInt-Seq overcomes this hurdle by utilizing a method of cross-linking that is reversible and thus preserves the T cells' RNA.

"The innovation of this system is that it combines an improved method that identifies T-cell receptors with more specificity with a chemical adaptation that makes this process compatible with droplet-based mRNA sequencing," Witte said. "This addresses challenges at the heart of finding T-cell receptors for treating cancer and other diseases as well as viral infections - from acute viruses like the virus that causes COVID-19 to chronic viruses like Epstein Barr or herpes."

Moving forward, the Witte lab is utilizing this technology to address a number of scientific questions, including identifying T-cell receptors that react to the SARS-CoV-2 virus and developing T-cell therapies for prostate cancer.

INFORMATION:

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, a UCLA Tumor Immunology Training Grant and the UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center, including support from the Hal Gaba Director's Fund for Cancer Stem Cell Rese

EUGENE, Ore. -- Jan. 12, 2020 -- Insufficient interactions with academic advisors and peers and financial problems are derailing career aspirations of women and minority groups pursing graduate degrees in the nation's highest-funded chemistry programs.

The challenges, tied to systemic gender and racial inequities, emerged from a deep analysis of data compiled in a 2013 American Chemical Society survey of 1,375 chemistry graduate students in the top 100 university chemistry departments in terms of research funding reported by the National Science Foundation.

The findings are detailed in a study, led by University of Oregon researchers, publishing this ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Wild bees are more affected by climate change than by disturbances to their habitats, according to a team of researchers led by Penn State. The findings suggest that addressing land-use issues alone will not be sufficient to protecting these important pollinators.

"Our study found that the most critical factor influencing wild bee abundance and species diversity was the weather, particularly temperature and precipitation," said Christina Grozinger, Distinguished Professor of Entomology and director of the Center for Pollinator Research, Penn State. "In the Northeastern United States, past trends and future predictions show a changing climate with warmer winters, more intense precipitation ...

A major risk of being hospitalised is catching a bacterial infection.

Hospitals, especially areas including intensive care units and surgical wards, are teeming with bacteria, some of which are resistant to antibiotics - they are infamously known as 'superbugs'.

Superbug infections are difficult and expensive to treat, and can often lead to dire consequences for the patient.

Now, new research published today in the prestigious journal Nature Microbiology has discovered how to revert antibiotic-resistance in one of the most dangerous superbugs.

The strategy involves ...

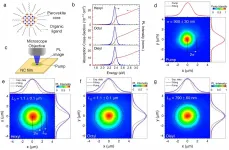

Producing clean energy and reducing the power consumption of illumination and personal devices are key challenges to reduce the impact of modern civilization on the environment. As a result, the surging demand for solar cells and light-emitting devices is driving scientists to explore new semiconductor materials and improve their performances, while lowering the production costs.

Semiconductor nanocrystals (materials with sizes about 10 nanometers, which is approximately 10,000 times thinner than our hair) hold great promise for these applications: they are cheap to produce, can be easily integrated in these devices and possess exceptionally enhanced properties upon interaction with ...

Curtin University researchers have used ancient crystals from eroded rocks found in stream sediments in Greenland to successfully test the theory that portions of Earth's ancient crust acted as 'seeds' from which later generations of crust grew.

The findings not only advance an understanding of the production of the Earth's crust through deep time, along with its structure and composition, but reveal a planet-wide crustal growth spurt three billion years ago when mantle temperatures peaked.

Lead author Professor Chris Kirkland, from Curtin University's Timescales of Mineral Systems ...

You are likely familiar with the serious consequences of anorexia for those who experience it, but you might not be aware that the disorder may not be purely psychological. A recent review from researchers at the University of Oxford in the open-access journal END ...

Highlights:

Severe cases of COVID-19 often include GI symptoms

Chronic diseases associated with severe COVID-19 are also associated with altered gut microbiota

A growing body of evidence suggests poor gut health adversely affects prognosis

If studies do empirically demonstrate a connection between the gut microbiota and COVID-19 severity, then interventions like probiotics or fecal transplants may help patients

Washington, D.C. - January 12, 2021 - People infected with COVID-19 experience a wide range of symptoms and severities, the most commonly reported including high fevers ...

PHILADELPHIA -- (Jan. 12, 2021) -- Scientists at The Wistar Institute have created an advanced humanized immune system mouse model that allows them to examine resistance to immune checkpoint blockade therapies in melanoma. It has revealed a central role for mast cells. These findings were published today in the journal Nature Communications.

Checkpoint inhibitors revolutionized therapeutic options for advanced melanoma. However, only a fraction of patients respond to this treatment and some relapse due to reemergence of therapy-resistant lesions.

"To better understand why some cancers do not respond or become resistant to checkpoint therapies, ...

Imagine you gave the exact same art pieces to two different groups of people and asked them to curate an art show. The art is radical and new. The groups never speak with one another, and they organize and plan all the installations independently. On opening night, imagine your surprise when the two art shows are nearly identical. How did these groups categorize and organize all the art the same way when they never spoke with one another?

The dominant hypothesis is that people are born with categories already in their brains, but a study from the Network Dynamics Group (NDG) at the Annenberg School for Communication has discovered a novel explanation. In an experiment in which people were asked to categorize unfamiliar shapes, individuals and small groups created ...

New research has found as climate change causes the world's oceans to warm, baby sharks are born smaller, exhausted, undernourished and into environments that are already difficult for them to survive in.

Lead author of the study Carolyn Wheeler is a PhD candidate at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University (Coral CoE at JCU) and the University of Massachusetts. She examined the effects of increased temperatures on the growth, development and physiological performance of epaulette sharks--an egg-laying species found only ...