Not as simple as thought: How bacteria form membrane vesicles

Researchers from the University of Tsukuba identify a novel mechanism by which bacteria form various types of membrane vesicles

2021-01-14

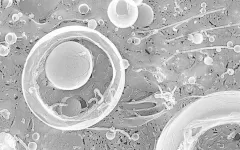

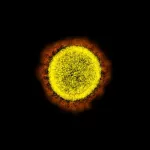

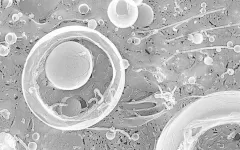

(Press-News.org) Tsukuba, Japan - Bacteria have the ability to form membrane vesicles to communicate with each other, but also to defend themselves against antibiotics. In a new study, researchers from the University of Tsukuba discovered a novel mechanism by which mycolic acid-containing bacteria, a specific group of bacteria with a special type of cell membrane, form membrane vesicles.

Bacteria have traditionally been classified on the basis of the composition of their cell envelopes. For example, microbiologists employ Gram staining to differentiate between bacteria that have a thick (Gram-positive) or thin (Gram-negative) cell wall. While bacterial membranes mostly act as protective barriers, they can also form protrusions to make membrane vesicles with diverse biological functions. For example, membrane vesicles may contain various biomolecules, such as DNA, which can be sent between bacteria and confer new abilities to the cells. Membrane vesicles have also been shown to be an important tool for bacteria to defend themselves against antibiotics and phages (viruses that infect bacteria). Recent studies have shown that bacteria form membrane vesicles in various ways, which in turn produces different types of membrane vesicles. While these studies mostly explored the biogenesis of membrane vesicles in Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, the mechanism of membrane vesicle formation in mycolic acid-containing bacteria (MCB), such as Mycobacteria tuberculosis that are responsible for tuberculosis, has remained unknown.

"Mycolic acid-containing bacteria are a very interesting group of bacteria because of their complex cell structure," says author of the study Dr. Toshiki Nagakubo. "The goal of our study was to understand how these cells form membrane vesicles."

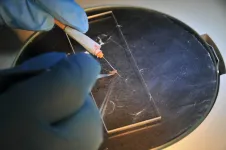

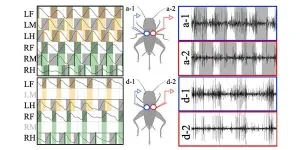

To achieve their goal, the researchers asked how environmental conditions influence the formation of membrane vesicles. They exposed the MCB Corynebacterium glutamicum to two different types of stress: DNA damage and envelope stress, that is an interference with cell wall or cell membrane synthesis. By employing electron microscopy, super resolution live-cell imaging and various biochemical analytical tools, the researchers found that under DNA-damaging conditions, MCB formed membrane vesicles with more diverse morphologies than under normal conditions, demonstrating how bacteria adapt and respond to their environment. They further showed that DNA damage induced membrane vesicle formation remarkably through cell death. On the contrary, exposing the bacteria to envelope stress via penicillin or biotin deficiency resulted in membrane vesicle formation through membrane blebbing. Interestingly, these various routes of membrane vesicle formation were similar in other MCB, demonstrating how the complex cell structure of MCB dictates the types of membrane vesicles this group of bacteria can form.

"These are striking results that provide insight into the mechanisms by which unicellular organisms, namely bacteria, form various types of membrane vesicles. These findings could be helpful for the development of novel therapeutics or vaccines," says corresponding author of the study Associate Professor Masanori Toyofuku.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-14

Food allergies have been increasing dramatically across the developed world for more than 30 years. For instance, as many as 8% of children in the U.S. now experience potentially lethal immune system responses to such foods as milk, tree nuts, fish and shellfish. But scientists have struggled to explain why that is. A prevailing theory has been that food allergies arise because of an absence of natural pathogens such as parasites in the modern environment, which in turn makes the part of the immune system that evolved to deal with such natural threats hypersensitive to certain foods.

In a paper published Jan. 14 in the journal Cell, four Yale immunobiologists propose an expanded explanation for the rise of food allergies -- the exaggerated ...

2021-01-14

Focusing on the largest health care system in the Northeast, the study is among the first to document the pandemic's impact on cancer screening and diagnosis.

Screening and diagnoses rebounded in the months following the first surge of the pandemic.

The authors urge those who delayed screenings during the height of the pandemic to contact their health care provider to discuss the potential need to reschedule one.

BOSTON - In one of the first studies to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer diagnoses, researchers at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women's ...

2021-01-14

HOUSTON - (Jan. 14, 2021) - Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine have discovered how therapeutics targeting RNA splicing can activate antiviral immune pathways in triple negative breast cancers (TNBC) to trigger tumor cell death and signal the body's immune response. A new study published in Cell shows that endogenous mis-spliced RNA in tumor cells mimics an RNA virus, leading tumor cells to self-destruct as if fighting an infection. Researchers suggest this mechanism could open new avenues for turning on the immune system in aggressive cancers like TNBC.

"We know therapeutics that partially interfere with RNA splicing can have a very strong impact on tumor growth and progression, but the mechanisms of tumor killing are largely ...

2021-01-14

A vector refers to an organism that carries and transmits an infectious disease, as mosquitoes do malaria.

Lead compounds are chemical compounds that show promise as treatment for a disease and may lead to the development of a new drug.

Antiplasmodial lead compounds are those that counter parasites of the genus Plasmodium, which is the parasite that infects mosquitoes and causes malaria in people.

The study findings were published in Nature Communications on 11 January 2021, at a time when malaria incidence generally peaks after the holiday season.

MOSQUITO INFECTION EXPERIMENT CENTRE

Professor Lizette Koekemoer, co-director of the WRIM and the National Research ...

2021-01-14

Recently, the innovation project watermelon and melon cultivation and physiology team of Zhengzhou Fruit Research Institute has made new progress in the metabolism regulation of sugar and organic acid in watermelon fruit. The changes of sugar and organic acid during the fruit development were analyzed and the key gene networks controlling the metabolism of sugar and organic acid during the fruit development were identified. These results provided a theoretical basis for watermelon quality breeding, which had important scientific significance for the development of watermelon industry and the improvement of watermelon breeding level in China. The related research results were published in the journals of Horticulture Research and Scientia Horticulturae.

The ...

2021-01-14

Research led by the University of Birmingham and Birmingham Women's and Children's NHS Foundation Trust has revealed new insight into the biological mechanisms of the long-term positive health effects of breastfeeding in preventing disorders of the immune system in later life.

Breastfeeding is known to be associated with better health outcomes in infancy and throughout adulthood, and previous research has shown that babies receiving breastmilk are less likely to develop asthma, obesity, and autoimmune diseases later in life compared to those who are exclusively formula fed.

However, up until now, the immunological mechanisms responsible for these effects have been very poorly understood. In this new study, ...

2021-01-14

Aerosols are suspensions of fine solid particles or liquid droplets in a gas. Clouds, for example, are aerosols because they consist of water droplets dispersed in the air. Such droplets are produced in a two-step process: first, a condensation nucleus forms, and then volatile molecules condense onto this nucleus, producing a droplet. Nuclei frequently consist of molecules different to those that condense onto them. In the case of clouds, the nuclei often contain sulphuric acids and organic substances. Water vapour from the atmosphere subsequently condenses onto these nuclei.

Scientists led by Ruth Signorell, Professor at the Department of Chemistry and Applied ...

2021-01-14

Leading cancer experts at the University of Birmingham have solved a long-standing question of how various types of mutations in just one gene cause different types of diseases.

A team of scientists at the University's Institute of Cancer and Genomic Sciences, led by Professor Constanze Bonifer, studied a gene known as RUNX1, which is responsible for providing instructions for the development of all blood cells and is frequently mutated in blood cancers.

The results of their research has shown that the balance of cells types in the blood is affected much earlier than previously thought, which is particularly important for families that carry ...

2021-01-14

Adaptability explains why insects spread so widely and why they are the most abundant animal group on earth. Insects exhibit resilient and flexible locomotion, even with drastic changes in their body structure such as losing a limb.

A research group now understands more about adaptive locomotion in insects and the mechanisms underpinning it. This knowledge not only reveals intriguing information about the biology of the insects, but it can also help to design more robust and resilient multi-legged robots that are able to adapt to similar physical damage.

The insect nervous system is comprised of approximately 105 to 106 neurons. Understanding ...

2021-01-14

Posidonia oceanica seagrass -an endemic marine phanerogam with an important ecological role in the marine environment- can take and remove plastic materials that have been left at the sea, according to a study published in the journal Scientific Reports. The article's first author is the tenure-track 2 lecturer Anna Sànchez-Vidal, from the Research Group on Marine Geosciences of the Faculty of Earth Sciences of the University of Barcelona (UB).

The study describes for the first time the outstanding role of the Posidonia as a filter and trap for plastics in the coastal areas, and it is pioneer ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Not as simple as thought: How bacteria form membrane vesicles

Researchers from the University of Tsukuba identify a novel mechanism by which bacteria form various types of membrane vesicles