(Press-News.org) In the inaugural issue of the journal Nature Aging a research team led by aging expert Linda P. Fried, MD, MPH, dean of Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, synthesizes converging evidence that the aging-related pathophysiology underpinning the clinical presentation of phenotypic frailty (termed as "physical frailty" here) is a state of lower functioning due to severe dysregulation of the complex dynamics in our bodies that maintains health and resilience. When severity passes a threshold, the clinical syndrome and its phenotype are diagnosable. This paper summarizes the evidence meeting criteria for physical frailty as a product of complex system dysregulation. This clinical syndrome is distinct from the cumulative-deficit-based frailty index of multimorbiditys. The paper is published online here.

Physical frailty is defined as a state of depleted reserves resulting in increased vulnerability to stressors that emerges during aging independently of any specific disease. It is clinically recognizable through the presence of three or more of five key clinical signs and symptoms: weakness, slow walking speed, low physical activity, exhaustion and unintentional weight loss.

The authors of this Perspectives article integrate the scientific evidence of physical frailty as a state, largely independent of chronic diseases, that emerges when the dysregulation of multiple interconnected physiological and biological systems crosses a threshold to critical dysfunction that severely compromises homeostasis, or stability among the body's physiological presses. The physiology underlying frailty is a critically dysregulated complex dynamical system. This conceptual framework implies that interventions such as physical activity that have multisystem effects are more promising to remedy frailty than interventions targeted at replenishing single systems.

Fried and colleagues then consider how this framework can drive future research to optimize understanding, prevention and treatment of frailty, which will likely preserve health and resilience in aging populations.

"We hypothesized that when Individual physiological systems decline in their efficiency and communication between cells and between systems deteriorate, this results in a cacophony of multisystem dysregulation which eventually crosses a severity threshold and precipitates a state of highly diminished function and resilience, physical frailty," said Fried, who is also director of the Robert N. Butler Columbia Aging Center.

"The key insight is simply that one's physiological state results from numerous interacting components at different temporal and spatial scales (e.g., genes, cells, organs) that create a whole unpredictably more than the parts," observes Fried.

For example, Fried notes that physical frailty prevalence and incidence has been linked to the interconnected dynamics of three major systems, altered energy metabolism through both metabolic systems, including glucose/insulin dynamics, glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, alterations in energy regulatory hormones such as leptin, ghrelin, and adiponectin, and through alterations of musculoskeletal systems function, including efficiency of energy utilization and mitochondrial energy production and mitochondrial copy number. Notably, across these systems, both energy production and utilization are abnormal in those who are physically frail.

The aggregate stress response system and its subsystems are also abnormal in physical frailty. Specifically, inflammation is consistently associated with being frail, including significant associations with elevated inflammatory mediators such as C-reactive protein, Interleukin 6 (IL-6, and white blood cells including macrophages and neutrophils, among others, in a broad pattern of chronic, low-grade inflammation. Each of these three systems mutually regulate and respond to the others in a complex dynamical system.

The authors recommend that multisystem fitness is needed to maintain resilience and prevent physical frailty, including macro-level interventions such as activities to improve physical activity or social engagement; the latter, apart from contributing to psychological well-being, also can increase physical and cognitive activity.

"There is strong evidence that frailty is both prevented and ameliorated by physical activity, with or without a Mediterranean diet or increased protein intake," noted Fried.

"These model interventions to date are nonpharmacologic, behavioral ones, emphasizing the potential for prevention through a complex systems approach."

"This work, conducted under the leadership of Dr. Linda Fried, is the culmination of nearly two decades of research characterizing the pathophysiology of the frailty syndrome. It should pave the way for further elucidating the underlying mechanisms of frailty pathogenesis," said Ravi Varadhan, PhD, PhD, Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins University, and a co-author. "The paper postulates that energetics - the totality of the processes involved in the intake, utilization, and expenditure of energy by the organism - is the key driver of frailty. Testing this hypothesis would be an important area of future research in aging."

INFORMATION:

Other co-authors are Alan Cohen, Université de Sherbrooke, Canada; Qian-Li Xue and Jeremy Walston, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; and Karen Bandeen-Roche, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The paper was supported by National Institute on Aging (Women's Health and Aging Study) I N01 AG012112, II M01 R000052; Pathogenesis of Physical Disability in Aging Women (MERIT Award) R37 AG019905; and Johns Hopkins University Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, P30AG021334.

Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

Founded in 1922, the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health pursues an agenda of research, education, and service to address the critical and complex public health issues affecting New Yorkers, the nation and the world. The Columbia Mailman School is the seventh largest recipient of NIH grants among schools of public health. Its nearly 300 multi-disciplinary faculty members work in more than 100 countries around the world, addressing such issues as preventing infectious and chronic diseases, environmental health, maternal and child health, health policy, climate change and health, and public health preparedness. It is a leader in public health education with more than 1,300 graduate students from 55 nations pursuing a variety of master's and doctoral degree programs. The Columbia Mailman School is also home to numerous world-renowned research centers, including ICAP and the Center for Infection and Immunity. For more information, please visit http://www.mailman.columbia.edu.

Astronomers have curated the most complete list of nearby brown dwarfs to date thanks to discoveries made by thousands of volunteers participating in the Backyard Worlds citizen science project. The list and 3D map of 525 brown dwarfs -- including 38 reported for the first time -- incorporate observations from a host of astronomical instruments including several NOIRLab facilities. The results confirm that the Sun's neighborhood appears surprisingly diverse relative to other parts of the Milky Way Galaxy.

Mapping out our own small pocket of the Universe is a time-honored quest within astronomy, and ...

NEW YORK (January 14) -- A new study co-authored by researchers from the Wildlife Conservation Society's (WCS) Global Conservation Program and the University of British Columbia (UBC) Faculty of Forestry introduces a classification called Resistance-Resilience-Transformation (RRT) that enables the assessment of whether and to what extent a management shift toward transformative action is occurring in conservation. The team applied this classification to 104 climate adaptation projects funded by the WCS Climate Adaptation Fund over the past decade and found differential responses toward transformation ...

A wide breadth of behaviors surrounding oral sex may affect the risk of oral HPV infection and of a virus-associated head and neck cancer that can be spread through this route, a new study led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center suggests. These findings add nuance to the connection between oral sex and oropharyngeal cancer -- tumors that occur in the mouth and throat -- and could help inform research and public health efforts aimed at preventing this disease.

The findings were reported Jan. 11 in the journal Cancer.

In the early 1980s, researchers realized that nearly all cervical cancer is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), a DNA virus from the Papillomaviridae family. Although about 90% of HPV infections ...

The higher a person's income, the more likely they were to protect themselves at the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic in the United States, Johns Hopkins University economists find.

When it comes to adopting behaviors including social distancing and mask wearing, the team detected a striking link to their financial well-being. People who made around $230,000 a year were as much as 54% more likely to increase these types of self-protective behaviors compared to people making about $13,000.

"We need to understand these differences because we can wring our hands, and we can blame and shame, but in a way it doesn't matter," said Nick Papageorge, the Broadus Mitchell Associate Professor of Economics. "Policymakers just need to recognize who is going ...

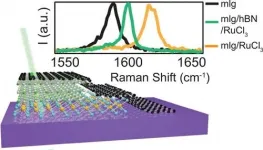

Physicists at Washington University in St. Louis have discovered how to locally add electrical charge to an atomically thin graphene device by layering flakes of another thin material, alpha-RuCl3, on top of it.

A paper published in the journal Nano Letters describes the charge transfer process in detail. Gaining control of the flow of electrical current through atomically thin materials is important to potential future applications in photovoltaics or computing.

"In my field, where we study van der Waals heterostructures made by custom-stacking atomically ...

ATLANTA--Compared to standard machine learning models, deep learning models are largely superior at discerning patterns and discriminative features in brain imaging, despite being more complex in their architecture, according to a new study in Nature Communications led by Georgia State University.

Advanced biomedical technologies such as structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI and fMRI) or genomic sequencing have produced an enormous volume of data about the human body. By extracting patterns from this information, scientists can glean ...

Philadelphia, January 14, 2021--Based on preclinical studies of an investigational drug to treat peripheral nerve tumors, researchers at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) as part of the Neurofibromatosis Clinical Trials Consortium have shown that the drug, cabozantinib, reduces tumor volume and pain in patients with the genetic disorder neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). The results of the Phase 2 clinical trial, co-chaired by Michael J. Fisher, MD at CHOP, were published recently in Nature Medicine.

"This is the second class of drugs to demonstrate ...

Many animal and insect species use Batesian mimicry - mimicking a poisonous species - as a defense against predators. The common palmfly, Elymnias hypermnestra (a species of satyrine butterfly), which is found throughout wide areas of tropical and subtropical Asia, adds a twist to this evolutionary strategy: the females evolved two distinct forms, either orange or dark brown, imitating two separate poisonous model species, Danaus or Euploea. The males are uniformly brown. A population group is either entirely brown (both males and females) or mixed (brown males and orange females).

City College of New York entomologist David Lohman and his collaborators studied the genome of 45 samples representing 18 subspecies across Asia to determine ...

While new research from West Virginia University economists finds that presidential inaugurations have gained popularity as must-see tourist events in recent years, major security threats will keep visitors away for the inauguration of President-Elect Joe Biden.

Published in "Tourism Economics," the study, by Joshua Hall, chair and professor of economics, and economic doctoral student Clay Collins, examined the impact of the inaugurations of Barack Obama and Donald Trump on hotel occupancy in the Washington, D.C.-area.

Daily occupancy rates around the inaugurations were four-to-six times higher than the next largest event in the sample. The research team also concluded ...

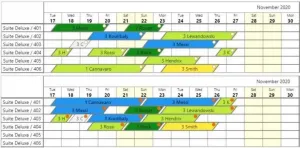

To achieve full occupancy, hotels used to rely exclusively on experience, concentration and human abilities. Then came online booking, which made the reservation collection process faster, but did not solve the risk of turning down long stays because of rooms previously booked for short stays.

To avoid overbooking (accepting more reservations than there is room for) in some cases online sales are blocked before hotels are completely booked. The solution that the University of Trento has just discovered could change the life of hotels by increasing the number of occupied rooms and, therefore, in the revenue of hotel owners.

For an average Italian hotel (50 rooms), ...